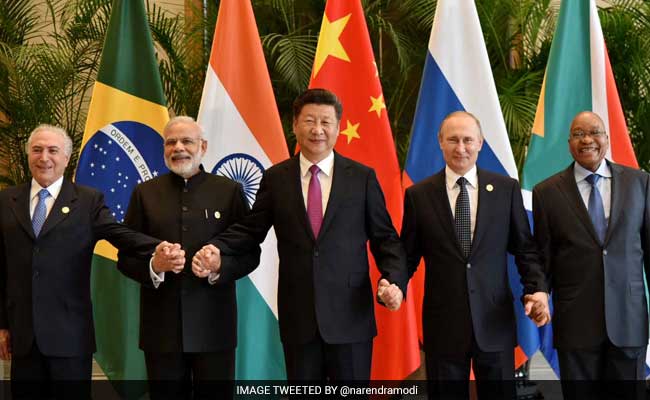

POWER PEOPLE: Brazil’s Michel Temer, India’s Narendra Modi, China’s Xi Jinping, Russia’s Vladimir Putin and South Africa’s Jacob Zuma

By Brahma Chellaney

The group of five nations is struggling to define a common identity and build cooperation among its members

On paper, the five BRICS countries look like a powerful grouping. Together they represent more than a quarter of the earth’s landmass, over 42 per cent of the global population, almost 25 per cent of the world’s GDP, and nearly half of the global foreign exchange and gold reserves. In reality, though, BRICS is struggling to define a common identity and build institutionalised cooperation among its members. Their Goa summit underscored inherent challenges, including building effective unity.

As the first important non-Western global initiative of the post-Cold War world, BRICS reflects ongoing global power shifts, including the slow retreat of Atlantic dominance. If BRICS can get its act together, it will be able to spur on fundamental changes in the global financial and governance systems.

Had BRICS pursued a more forward-looking approach, it could have simply called itself the R-5 after the names of its members’ currencies — the real, rand, ruble, renminbi and rupee — and presented itself, in contrast to the obsolescent G-7, as the face of the future.

The plain fact is that the challenges BRICS faces today are fundamental. These disparate countries have starkly varying political systems, economies, and national goals, and are located in different corners of the globe. There is little in common among the BRICS states.

For example, what is common between the world’s largest democracy, India, and the largest autocracy, China? The biggest real estate claimed by a revanchist China is an Indian state almost three times larger than Taiwan — Arunachal Pradesh, an ecological paradise. How can BRICS create rules-based cooperation among its members if international norms of behaviour are flouted, as by China’s territorial creep in the South China Sea and its shielding of Pakistani terrorism?

To compound BRICS’ challenges, the Brazilian, Russian and South African economies have nose-dived, even as China’s faltering growth and downside deflationary risks have unsettled global markets. Only India has defied BRICS’ slump, priding itself as the world’s fastest-growing major economy.

Almost six years after it expanded from a four- to a five-member grouping, BRICS has yet to evolve into a coherent grouping with defined goals and an institutional structure. Of course, it has created the Shanghai-based New Development Bank and set up, as a shield against global liquidity pressures, the $100-billion, China-dominated Contingent Reserve Arrangement. The real winner from both these initiatives is China, with BRICS left carrying the can.

The Goa summit was a reminder that BRICS has yet to devise a common action-plan to go forward. BRICS cannot remain just a ‘talk shop’.

To be sure, the annual BRICS summit provides a useful platform for bilateral discussions on the sidelines. Some member states, by piggybacking on the BRICS summit, hold their own bilateral summits before or after the event, as was illustrated by the India-Russia summit.

Still, BRICS faces nagging questions about whether its members, with their different priorities and interests, can unite on key international issues. If BRICS is to build collective clout, its members must frame common objectives and approaches to tackling the pressing international issues. Take the scourge of terrorism: At China’s insistence, the Goa Declaration omitted any reference to ‘cross-border terrorism’ or ‘state sponsorship’ of terror or even to any Pakistan-based group despite mentioning ISIS and al-Nusra.

The G-7 began as a discussion platform like BRICS but, by defining its members’ common interests, it advanced within years to joint coordination on key international issues. BRICS, lacking the shared political and economic values that bind the G-7 members, cannot stay relevant if it does little more than bring together its leaders and various stakeholders for discussions. Indeed, the most important bilateral relationship for each BRICS country is not with another BRICS member but with the United States.

Worse still, a domineering China is using BRICS to advance its own agenda, including expanding the renminbi’s international role. Lending and trading in the renminbi helps China to boost its exports and clout. China’s hidden export subsidies, meanwhile, have been systematically undermining manufacturing in the other BRICS states, especially India and Brazil. For Brazil, India, Russia and South Africa, BRICS offers largely symbolic benefits.

Even on international institutional reforms, China is hardly on the same page as the other members. It is a revisionist power with respect to the global financial architecture. It seeks to dominate the first tangible challenge to the Bretton Woods institutions, as symbolised by the BRICS’ New Development Bank and the China-created Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

China, however, is the status quo power in regard to the UN system and wishes to remain Asia’s sole country with a permanent seat in the Security Council, which means keeping India out. Its strategy, by extension, also seeks to shut India out of other political institutions, including the Nuclear Suppliers Group.

Against this backdrop, if BRICS remains just a ‘talk shop’, it will not only fail to fulfil its true potential but will also wither away under the weight of its contradictions.

The Goa summit did little to belie the contention of cynics that BRICS is just an acronym without substance.

Courtesy: Hindustan Times