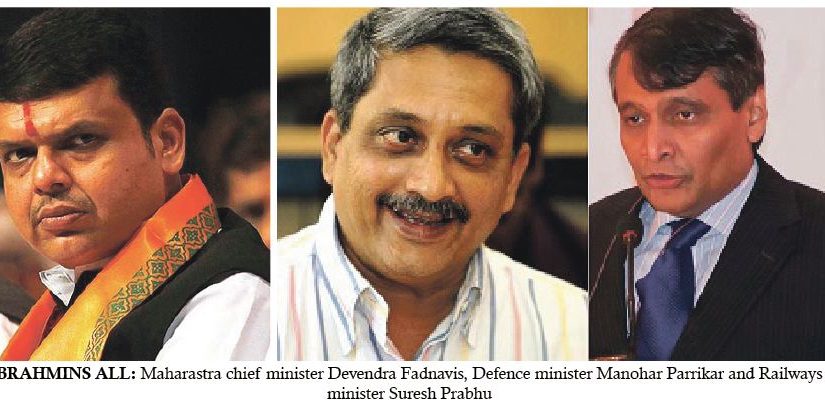

The BJP governments at centre and states are full of Brahmins, including Railways minister Suresh Prabhu, Defence minister Manohar Parrikar and Maharashtra chief minister Devendra Fadnavis. Scholars say the rise in representation is not linked to caste factors, but part of larger social and political trends

By Makarand Gadgil

Immediately after Devendra Fadnavis was elected leader of the legislative wing of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) on October 28, a message began circulating among various WhatsApp groups.

The Maharashtra government had removed Brahmin priests from a Vithoba temple in Pandharpur, it went, but due to divine intervention, a Brahmin chief minister – Fadnavis – would offer prayers for Lord Vithoba at Kartiki Ekadashi.

As per tradition since the modern state of Maharashtra state came into being in 1960, it is always the state’s chief minister who leads the prayers for Lord Vitthal – or Vithoba – on two holy days, Ashadhi Ekadashi and Kartiki Ekadashi, the 11th day of the months of Ashadh and Kartik, according to the Hindu calendar. Vitthal is considered to be the presiding deity of Maharashtra.

As it happened, Fadnavis stayed away, smartly sending his non-Brahmin minister Eknath Khadse, who belongs to the Leva Patil Other Backward Classes (OBC) to perform the pooja.

Earlier, in January, the Supreme Court gave a verdict which ended the monopoly of Brahmin priests over the duty of performing rituals at Pandharpur’s Vithoba temple. In August, the state government appointed some non-Brahmins and women as priests at the temple.

The message on WhatsApp and other social media platforms reflected the frustration of Maharashtrian Brahmins, who have felt marginalised from the political process since Independence, as well as their joy at the anticipated return of the Brahmin at the helm of the state’s political affairs.

But now, on the surface, recent political developments suggest that Maharashtrian Brahmins may be back in the reckoning.

In the central cabinet, Maharashtrian Brahmins Nitin Gadkari, Suresh Prabhu and Prakash Javadekar hold important portfolios. Manohar Parrikar, a Brahmin from Goa, is of Maharashtrian origin, as is Lok Sabha speaker Sumitra Mahajan, although she was elected from Indore.

In the party too, they occupy important positions at the national level. BJP vice-president Vinay Sahasrabuddhe, joint general secretary (organisation) Satish Velankar and secretary Poonam Mahajan are all Maharashtrian Brahmins.

Although Fadnavis is the only Brahmin in the state cabinet, it is expected that at least one more will brought in when the cabinet is expanded, according to a senior leader in state BJP. Eight BJP Brahmin candidates won the elections to the state assembly, the highest number since 1990.

Sadanand More, former professor of philosophy in Savitribai Phule, Pune University, and a specialist in the social reform movements of Maharashtra, said, “The change of government, both at central and state, has taken place because of widespread resentment against governments in both places and the promise of development given by Narendra Modi. It is not a vote for or against any particular caste or caste group.”

“Those who have become ministers in the central cabinet or people like Fadnavis have not got the positions on the strength of their caste but their individual contribution to party and society and now they will have to be extra cautious in their behaviour and demonstrate that they are not promoting the Brahmin community’s interests.”

Maharashtrian Brahmins not only dominated Maharashtra’s politics but the nation’s too from early 18th century till the early part of the last century. From then, until the death of Congress leader Lokmanya Tilak in 1920, Maharashtrian Brahmins enjoyed a virtual hegemony in politics.

Tilak was not the only Maharashtrian Brahmin to play a key role Maharashtra’s social, cultural and political renaissance in late 19th and early 20th centuries. Other such personalities included Mahadev Govind Ranade, Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Gopal Ganesh Agarkar. Their prominence also gave rise to an anti-Brahmin movement.

More said, “The deep-rooted resentment against Brahmins came from the fact that in British times too they became the ruling elite. They were the first recipients of English education, so they occupied posts of authority in government. Some turned against the government with English education, so they also occupied opposition space and some started championing the cause of social reforms, so in this field too they were leaders and such complete domination did not go down well with other castes.”

The voice against Brahmin hegemony was raised by the likes of Mahatma Jyotiba Phule, who started India’s first women’s school in the mid-19th century, and Chhatrapati Shahuji Maharaj, who first introduced reservations for Dalits in government jobs in his princely state in the early 20th century and financed Babasaheb Ambedkar’s studies abroad. Ambedkar later became India’s pre-eminent Dalit leader.

Raosaheb Kasbe, a Dalit intellectual said, “In 1919, Indians got the right to vote for central and provincial legislative councils.

Though right of franchise was limited, it made leaders of Bahujans (a term used to describe non-brahmins) realise the power of franchise and thus numbers in democracy; so they started more vigorously joining the national movement or the Congress in greater numbers. Till then they viewed the Congress as a tool of upper castes (Brahmins) to overthrow Britishers and establish the rule of the Peshwas (Brahmins rulers) once again.”

If the 1919 Montagu-Chelmsford reforms marked the beginning of the end of Brahmin hegemony in Maharashtra’s politics, Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination by Nathuram Godse, a Brahmin from Pune, in 1948 completed the process.

Aroon Tikekar, a well-known scholar and former president of the Asiatic Society, said, “What happened after Independence or, more so, after 1960, was reverse discrimination against Brahmins. As part of this reverse discrimination, they were not only marginalised from the political process but their contribution to social, cultural and educational fields was also ignored.”

“Because of all this, the Brahmin community further went into a shell and they started only concentrating on their education and careers and became indifferent to what was happening around them.”

The last time a Brahmin was made a minister in a Congress government in Maharashtra was in the mid-1990s, when Arun Divekar was the minister of state in chief minister Sharad Pawar’s cabinet. During the 15-year rule of the Congress and Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) between 1999-2014, there was not a single Brahmin minister.

In fact, anti-Brahminism was so strong in Maharashtra’s politics that the late BJP general secretary Pramod Mahajan never considered a career in state politics for himself.

Even during the 2014 assembly campaign, NCP leaders like Chhagan Bhujbal and R R Patil tried to play the anti-Brahmin card by asking voters if they wanted a government led by the likes of Fadanvis and Gadkari – two Brahmins – in Maharashtra.

However, scholars don’t see the boom in representation of Brahmins in the central cabinet and state legislature as some sort of a Brahminical conspiracy. Rather, they attribute this peculiar phenomenon to prevalent social, economic and political conditions.

Courtesy: Live Mint