Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

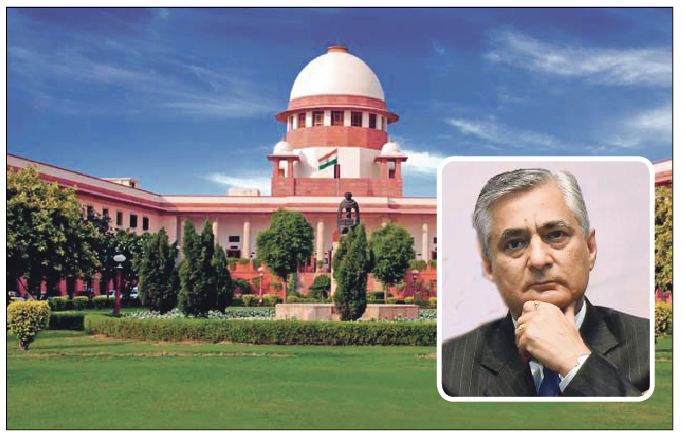

COMMUNAL CAMPAIGN BANNED

Appeal, Corruption, Goa Election 2017, Jan 14 - Jan 20 2017, Section January 14, 2017LAST LAUGH: Chief Justice T S Thakur ,who has been involved in a bitter battle with prime minister Narendra Modi, ruled that any appeals for votes on the basis of caste, religion, race or language would attract severe penalties including fines and imprisonments

A candidate is liable for disqualification on the basis of an appeal on grounds of religion, race, caste or community in the Assembly Elections being held in Goa on February 4. This rules out vote seeking by either the Bharatiya Janata Party in the name of Hindutva, the Bharatiya Bhasha Suraksha Manch in the name of Marathi, and swamis, maulanas or priests in the name of religion, caste or language

(Excerpts from the judgement of the chief justice of the Supreme Court)

THE legislative history of Section 123(3) as it now forms part of the statute has been traced in the order proposed by brother Lokur, J I, can make no useful addition to that narrative which is both exhaustive and historically accurate. I may, perhaps pick up the threads post 1958 by which time amendments to the Representation of People Act, 1951 had brought Section 123(3) to read as under:

‘The systematic appeal by a candidate or his agent or by any other person with the consent of a candidate or his election agent to vote or refrain from voting on the grounds of caste, race, community or religion or the use of, or appeal to, religious symbols or the use of, or appeal to, national symbols, such as the national flag or national emblem, for the furtherance of the prospects of that candidate’s election.’

A close and careful reading of the above would show that for an appeal to constitute a corrupt practice, it had to satisfy the following ingredients:

CONSENT NEEDED

(i) The appeal was made by the candidate, or his agent, or by any other person with the consent of the candidate or his election agent;

(ii) The appeal was systematic;

(iii) The appeal so made was to vote or refrain from voting at an election on the ground of caste, race, community, or religion or the use of or appeal to religious symbols or the use of or appeal to national symbols such as national flag or the national emblem; and

(iv) The appeal was for the furtherance of the prospects of the candidate’s election, by whom or whose behalf the appeal was made.’

CORRUPT ACT

WHAT is noteworthy is that Section 123(3) as it read before the amendment of 1961, did not make any reference to the ‘candidate’s religion’ or the ‘religion of his election agent’or the ‘person who was making the appeal with the consent of the candidate or his agent’ or even of the ‘voters’, leave alone the ‘religion of the opponent’ of any such candidate.

All that was necessary to establish the commission of a corrupt practice was a systematic appeal by a candidate, his election agent or any other person with the consent of any one of the two, thereby implying that an appeal in the name of religion, race, caste, community or language or the use of symbols referred to in Section 123(3) was forbidden regardless of whose religion, race, caste, community or language was invoked by the person making the appeal. All that was necessary to prove was that the appeal was systematic and the same was made for the furtherance of the prospects of a candidate’s election.

Then came the Bill for amendment of Section 123 of the Act introduced in the Lok Sabha on August 10, 1961 which was aimed at widening the scope of corrupt practice and to provide for a new corrupt practice and a new electoral offence. The notes on clauses attached to the Bill indicated that the object behind the proposed amendment was (a) to curb communal and separatist tendencies in the country (b) to widen the scope of the corrupt practice mentioned in sub-section (3) of Section 123 of the Act and (c) to provide for a new corrupt practice as in sub-clause (b) of clause 25. The proposed amendment was in the following words:

‘25. In Section 123 of the 1951 Act,

(a) In clause (3) –

(i) The word “systematic” shall be omitted,

(ii) For the words “caste, race, community or religion”, the words “religion, race, caste, community or language” shall be substituted;

(iii) (b) after clause (3), the following clause shall be inserted, namely:

“(3A) The promotion of, or attempt to promote, feelings of enmity or hatred between different classes of the citizens of India on grounds of religion, race, caste, community, or language, by a candidate or his agent or any other person with the consent of a candidate or his election agent for the furtherance of the prospects of that candidate’s election.”’

BILL AMENDED

MOU TANGLE: Subhash Velingka, convenor of BBSM, will not be able to make appeals in the name of protecting Marathi and demanding the suspension of grants to English Medium Schools.

THE bill proposing the above amendment was referred to a select committee who re-drafted the same for it was of the view that the amendment as proposed did not clearly bring out its intention. The redrafted provision was, with the minutes of dissent recorded by Ms Renu Chakravartty and Mr Balraj Madhok, debated by the Parliament and enacted to read as under:

‘The appeal by a candidate or his agent or by any other person with the consent of a candidate or his election agent to vote or refrain from voting for any person on the ground of his religion, race, caste, community or language or the use of, or appeal to, religious symbols or the use of, or appeal to, national symbols, such as the national flag or the national emblem, for the furtherance of the prospects of the election of that candidate or for prejudicially affecting the election of any candidate.

(3A) The promotion of, or attempt to promote, feelings of enmity or hatred between different classes of the citizens of India on grounds of religion, race, caste, community, or language, by a candidate or his agent or any other person with the consent of a candidate or his election agent for the furtherance of the prospects of election of that candidate or for prejudicially affecting the election of any candidate.’

RACIST : The Chief Minister designate of the MGP coalition Sudin Dhavalikar could be disqualified for demanding the shifting of the Portuguese Consulate and his remarks against the Portuguese on the grounds of making racist comments.

The single noteworthy change that was by the above amendment brought about in the law was the deletion of the word “systematic” as it appeared in Section 123 (3) before the amendment of 1961. The purpose underlying the proposed deletion obviously was to provide that an appeal in the name of religion after the amendment would constitute a corrupt practice even when the same was not systematic.

In other words, a single appeal on the ground of religion, race, caste, community or language would in terms of the amended provision be sufficient to annul an election. The other notable change which the amendment brought about was the addition of the words “or for prejudicially affecting the election of any candidate” in Section 123 (3) which words were not there in the earlier provision.

That the purpose underlying the amendment was to enlarge the scope of corrupt practice was not disputed by the learned counsel for the parties before us. That the removal of the word “systematic” and the addition of the words “prejudicially affecting the election of any candidate” achieved that purpose was also not disputed.

What was all the same strenuously argued by Mr Shyam Diwan was that even when the purpose of the amendment was to widen the scope of the corrupt practice under Section 123 (3), it had also restricted the same by using the word “his” before the word “religion” in the amended provision. According to Mr Diwan, the amendment in one sense served to widen but in another sense restrict the scope of corrupt practice.

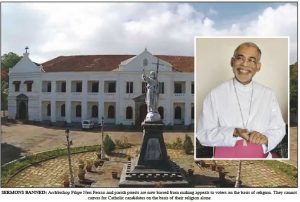

SERMONS BANNED : Archbishop Filipe Neri Ferrao and parish priests are now barred from making appeals to voters on the basis of religion. they cannot canvas for Catholic candidates on the basis of their religion alone.

I have found it difficult to accept that submission. In my view the un-amended provision extracted earlier made any appeal in the name of religion, race, caste, community or language a corrupt practice regardless of whose religion, race, caste, community or language was involved for such an appeal. The only other requirement was that such an appeal was made in a systematic manner for the furtherance of the prospects of a candidate.

Now, if that was the legal position before the amendment and if the Parliament intended to enlarge the scope of the corrupt practice as indeed it did, the question of the scope being widened and restricted at the same time did not arise. There is nothing to suggest either in the statement of objects and reasons or contemporaneous record of proceedings including notes accompanying the bill to show that the amendment was contrary to the earlier position intended to permit appeals in the name of religion, race, caste, community or language to be made except those made in the name of the religion, race, caste, community or language of the candidate for the furtherance of whose prospects such appeals were made.

Any such interpretation will not only do violence to the provisions of Section 123(3) but also go against the avowed purpose of the amendment. Any such interpretation will artificially restrict the scope of corrupt practice for it will make permissible what was clearly impermissible under the un-amended provision.

The correct approach, in my opinion, is to ask whether appeals in the name of religion, race, caste, community or language which were forbidden under the un-amended law were actually meant to be made permissible, subject only to the condition that any such appeal was not founded on the religion, race, caste, community or language of the candidate for whose benefit the same was made.

WIDENED SCOPE

THE answer to that question has to be in the negative. The law as it stood before the amendment did not permit an appeal in the name of religion, race, caste, community or language, no matter whose religion, race, community or language was invoked. The amendment did not intend to relax or remove that restriction.

On the contrary, it intended to widen the scope of the corrupt practice by making even a ‘single such appeal’ a corrupt practice which was not so under the un-amended provision. Seen both textually and contextually, the argument that the term “his religion” appearing in the amended provision must be interpreted so as to confine the same to appeals in the name of “religion of the candidate” concerned alone does not stand closer scrutiny and must be rejected.

There is thus ample authority for the proposition that while interpreting a legislative provision, the courts must remain alive to the constitutional provisions and ethos, and that interpretations that are in tune with such provisions and ethos ought to be preferred over others.

Applying that principle to the case at hand, an interpretation that will have the effect of removing the religion or religious considerations from the secular character of the state or state activity ought to be preferred over an interpretation which may allow such considerations to enter, affect or influence such activities.

Electoral processes are doubtless secular activities of the state. Religion can have no place in such activities, for religion is a matter personal to the individual with which neither the state nor any other individual has anything to do. The relationship between man and God and the means which humans adopt to connect with the almighty are matters of individual preferences and choices.

The state is under an obligation to allow complete freedom for practising, professing and propagating religious faith to which a citizen belongs in terms of Article 25 of the Constitution of India, but the freedom so guaranteed has nothing to do with secular activities which the state undertakes.

The state can and indeed has in terms of Section 123(3) forbidden interference of religions and religious beliefs with secular activity of elections to legislative bodies.

To sum up: An appeal in the name of religion, race, caste, community or language is impermissible under the Representation of the People Act, 1951 and would constitute a corrupt practice sufficient to annul the election in which such an appeal was made, regardless whether the appeal was in the name of the candidate’s religion or the religion of the election agent or of the opponent or voter.

The sum total of Section 123 (3) even after amendment is that an appeal in the name of religion, race, caste, community or language is forbidden even when the appeal may not be in the name of the religion, race, caste, community or language of the candidate for whom it has been made.

So interpreted religion, race, caste, community or language would not be allowed to play any role in the electoral process and should an appeal be made on any of those considerations, the same would constitute a corrupt practice. With these few lines, I answer the reference in terms of the order proposed by Lokur, J.