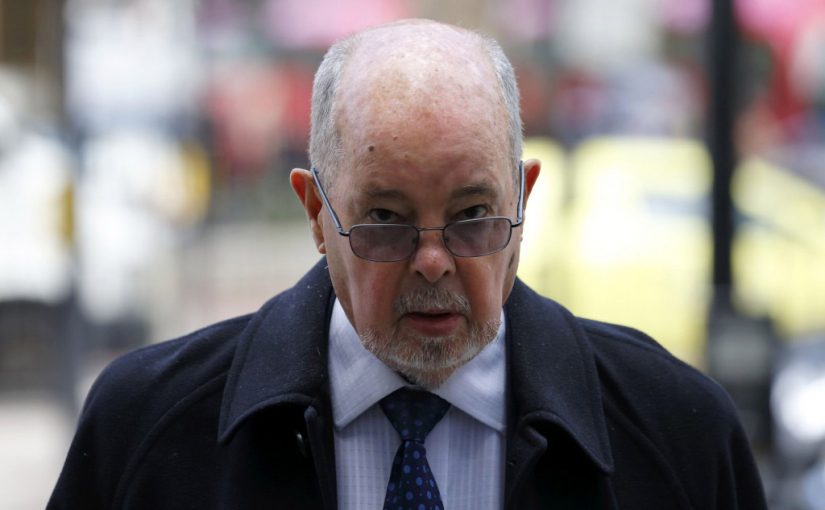

HARD WORK: From copyboy to the man who covered it all, Phillip Knightley wrote about his life and career with candour in his autobiography A Hack’s Progress

Phillip Knightley was among the greatest journalists of all time. He was an Australian who made a career for himself in the Sunday Times in London. His Indian connection was as editor of Imprint and his Mangalorean wife Yvonne Fernandes. Knightley, who spent Christmas and New Year in Goa every year, died in December

By Ian Jack

Phillip Knightley, who died aged 87 on December 7, 2016, was one of the most accomplished reporters of his generation: his craftsmanship underpinned some of the 20th century’s most memorable newspaper scoops and campaigns. He made a crucial contribution to the Sunday Times’ thalidomide exposé; revealed how the world’s biggest meat retailers – the Vestey family – had avoided taxation for six decades; and shed new light on problematic figures such as Lawrence of Arabia and the spy Kim Philby, with whom he corresponded for 20 years.

He tempered an omnivorous curiosity with a resilient scepticism – not least about his own trade of journalism, which he came to see was greatly overrated as a force for change. His truth-seeking had full play in his 1975 book The First Casualty, an account of the mendacity and myth-making of war correspondents, beginning in Crimea, but it did not in the end prevent the Sunday Times publishing the hoax Hitler diaries, when his caution went disregarded.

Like several other journalists who came to prominence in Fleet Street, and particularly on the Sunday Times, in the 1950s and 60s, Knightley was an Australian, born in Sydney. His father, Phillip, was a songwriter and his mother, Alice (née Iggleden), until her marriage, a clerk with the city gas company. They lived frugally, and when their son’s exam grades fell short of the qualifications for university entrance, he took a job with Frank Packer’s Consolidated Press, where, as a copy boy on the Sydney Daily Telegraph, he ran messages for reporters and also, according to his autobiography, A Hack’s Progress (1997), “collected their laundry [and] put them on a train or tram when they were drunk”.

He became a reporter himself on the Northern Star, a small daily published in the dairy town of Lismore near the New South Wales-Queensland border, but left after a year to join a British firm of South Sea traders in Fiji. The port there was exactly as he had expected – “straight out of Lord Jim” – but the job bored him and he quit to join a local paper, the Oceania Daily News, where his indiscreet social column, Round the Town With Suzanne, got him into trouble with the colonial authorities.

In later life, Knightley looked the model of probity. His domed head and neat beard led to frequent comparisons with Lenin. He talked courteously to everyone, never raised his voice and in any journalistic crisis was always the calmest person in the room.

In fact, he had an adventurous, larrikin side to him. After Fiji came a spell as a docks reporter in Melbourne, interviewing hopeful migrants from Europe as soon as they landed, before he joined the Sydney Daily Mirror on the crime beat. But until he was in his 30s he never felt entirely confident of his prospects as a journalist: he tried selling vacuum cleaners to Australian housewives and peanut-vending machines to London pubs; he appeared on the television quiz-show ‘What’s My Line?’ as a beachcomber and set off down the Thames to sail round the world on a 44-foot yacht, which turned back at Falmouth, Cornwall.

More successfully, at least for a short time, he jointly owned and ran a Chelsea restaurant, the Old Vienna, which employed waitresses in Tyrolean dress and, at weekends, a yodeller or two. From these experiences he drew interesting lessons that he was happy to pass on. His days as a restaurateur, for example, taught him that a good rubbing down with lemon juice could revitalise a piece of the worst-smelling old steak, and that cooked oysters, being the fresh oysters of the day before, were always best avoided.

He had reached Britain with no job in prospect some years before, late in 1954, but soon got employment in the London offices of his old Sydney paper and there learned that sensational stories could be conjured from almost nothing – a piece about a “lonely” baby kangaroo in the pet shop at Harrods, for example, raised emotional demands from readers back home that Knightley should buy this Australian symbol and find a good home for him (which he did, with the Duke of Bedford).

But he found the work disillusioning and sometimes unpleasant – he was never cut out to be a hit-and-run reporter – and in 1960 he set off for Sydney overland by train to Basra, in Iraq, and then by ship to Mumbai (then Bombay), where as luck had it a new literary magazine named Imprint needed a managing editor. The work was not taxing – condensing books, reading proofs, answering readers’ letters – and he was paid enough to enjoy old imperial habits such as tennis, swimming, sundowners and toasted mutton sandwiches. He stayed for two or three years – to discover, much later, that the magazine and therefore his pleasant lifestyle had been funded by the CIA.

Serious journalism began after he returned to London in 1963, his confidence in the future boosted by a lottery win in Australia. He began to freelance for the Sunday Times, which he felt was everything a good newspaper should be, and his persistence as a researcher and clarity as a writer soon gave him a regular byline. He presented his copy one paragraph to a page, double-spaced, with no run-ons or crossings-out or hand-written insertions – just as writers were supposed to (so that their pieces could be easily distributed among hot-metal typesetters), but which very few did so neatly. The writing was unmannered and straightforward – it lacked any notable style or “personality” – but it could clarify the most complicated (and often legally fraught) stories without sacrificing factual accuracy or losing the reader’s interest.

Under the successive editorships of Denis Hamilton and Harold Evans, the Sunday Times became celebrated for its investigative journalism and what would now be called long-form reporting. In the campaign for the proper compensation of the thalidomide victims, Knightley’s first role was to write the narrative that told how the drug came to be developed in Germany and sold under licence by the Distillers Company in Britain after inadequate testing. The newspaper had paid £10,500, probably illegally, for company documents that rebutted Distillers’ defence, but they were scientific papers, often in German, that needed painstaking translation and indexing by a small editorial team assembled for the purpose. Knightley began to fashion his story from this difficult and continually growing pile of raw material in 1968, and, after many interruptions, completed the 12,000-word narrative in 1971.

Courtesy: The Guardian

Apart from his coverage of the thalidomide scandal, Knightley is best known for describing the extent of Kim Philby’s duplicity, one of Britain’s most infamous spy scandals of the 20th century. Philby, who was one of the highest-ranking officers in the British intelligence service, had secretly been a Soviet mole since the 1930s, along with several other communist-inspired upper-class students from Cambridge University, known as the Cambridge Five. After Philby was exposed as a spy by British intelligence officers in 1963, he settled in Moscow. Knightley corresponded with him for several years, asking for permission to interview him. Philby finally consented in 1988. Knightley, along with team members Bruce Page and David Leitch, eventually published the book, ‘The Spy Who Betrayed a Generation’. Philby’s own book ‘My Silent War, the Autobiography of a Spy’, was a collaboration with Knightley