Recent studies reveal large scale exploitation of women in tourism, from trafficking for sex to massage parlours to violation of labour rules

IN 1950, the top 15 destinations of the world absorbed 88 per cent of international arrivals. In 1970, this proportion dipped to 75 per cent and even further to 57 per cent in 2005, reflecting the emergence of new destinations, many in developing countries.

This paper explores what this growth has meant for women – particularly in destinations of the global south. To what extent do they benefit? Has tourism opened doors for women? Has its unstoppable growth contributed to women‘s empowerment?

The paper examines the status of women and their leadership in tourism, the nature of women’s employment in tourism, women in tourism’s informal sector, the effect of depletion of natural resources on women and the challenges to women’s rights as stakeholders in all aspects of tourism development.

The feminisation and informalisation of the workforce in tourism, particularly in developing countries, is a matter of concern. Unfortunately, few research studies focus on the gender dimension resulting in little quantitative data on this trend. Women are seen, and hence favoured, as a passive, compliant and sometime invisible workforce that will accept low wages without demanding their labour and human rights. What remains constant is the low economic value accorded to work performed by women in conditions of exploitation, no job security and violations of human rights.

The feminisation and informalisation of the workforce in tourism, particularly in developing countries, is a matter of concern. Unfortunately, few research studies focus on the gender dimension resulting in little quantitative data on this trend. Women are seen, and hence favoured, as a passive, compliant and sometime invisible workforce that will accept low wages without demanding their labour and human rights. What remains constant is the low economic value accorded to work performed by women in conditions of exploitation, no job security and violations of human rights.

This occurs directly through prohibitions on labour organisation and indirectly through further abuses where women have claimed rights such as to organise or to be free from sexual harassment. Many women workers face difficult, often exploitative conditions.

India’s national newspapers carried a horrifying story of a woman working in an ayurvedic massage parlour in Kerala who was allegedly set on fire by her employer after she refused sexual favours to clients.

The International Labour Organisation published a report highlighting the high levels of violence, stress and sexual harassment in hotels, catering and tourism. Unsurprisingly, it is mostly women in junior positions who experience these problems, but unlike in other sectors, women face harassment not only from colleagues and managers but also from clients.

Factors such as late working hours, service of alcohol, dress codes, racism, negative attitudes towards service staff and the uninhibited, sexualised nature of tourism and tourism promotion contribute to a high-risk environment for women and younger workers, as well as ethnic minority, migrant and part-time workers

That these attitudes and difficulties prevail primarily in small scale enterprises is another myth that needs to be exposed. It took India’s national airline – Air India – six decades to acknowledge that women can supervise cabin crew as ably as men! Prior to the announcement in December 2005, men and women at Air India had different employment conditions, with female cabin crew forced to retire many years earlier than their male counterparts.

Sexist and gendered attitudes abound, making it difficult for women at all levels to claim equality and equity. Chief justice of Karnataka High Court Cyriac Joseph, told an all-woman audience at the Asia Women Lawyers’ Conference on the theme “Women’s rights are human rights’: “there was no point in women trying to be men and do all that a man is expected to do.”

Cautioning women, he said, “Once you lose your womanhood, there is nothing left to be protected.”

Invisible Labour

THE informal sector is the most direct source of income for local communities in tourism in developing countries. In the developing world, 60 per cent of women (in non-agricultural work) work in the informal sector. Much of this is linked directly and indirectly to tourism.

The role of women in informal tourism settings such as running home-stay facilities, restaurants and shacks, crafts and handicrafts, handlooms, small shops and street vending is significant. But these roles and activities that women perform in tourism are treated as invisible or taken for granted. The need to acknowledge the important economic contribution of women and ensure for them, access to credit, capacity building and enhanced skills, access to the market, encouragement to form unions, associations and cooperatives to increase their bargaining power and to ensure that their safety, health and social security needs are met is critical.

Creating opportunities for income generating activities, effective marketing and integrating women’s entrepreneurship with various government schemes to promote women’s self employment, would be an important component to promote women’s participation in tourism development. The sharing of experiences in tourism, understanding and demystifying complex official documents, such as tourism policies, master plans, related to the industry, providing information about access to documents are also important steps.

Community-based tourism initiatives, particularly of local women’s groups and co-operatives can be an accessible and suitable entry point for women’s participation in tourism. They seem to generate more long-term motivation than initiatives from outside.

These activities help to create financial independence for local women and help them to develop the necessary skills and improve their education, which in turn increase self-esteem and help create more equitable relationships in families and communities.

Women and Natural Resources

THERE is a direct correlation between the depletion of natural resources and increased burden on women in daily work in any region of the world. When tourism restricts community access to, or contributes to, the depletion of natural resources, it is women not only as homemakers, but also as community members, who suffer the most.

Women’s access to and control over forest produce and water comes into sharp conflict when tourism usurps these very resources needed to fulfil their life and livelihood needs. The daily burden on women of finding water for the household or firewood for cooking is often doubled or tripled. When tourism displaces people from traditional livelihoods or, worse still, physically displaces them, the worst affected are women who are engaged in the bulk of ancillary occupations like tobacco cultivation, coconut harvesting, fish sorting and processing which are jeopardised through such displacement.

Transition from certain activities to others, for example away from agriculture, could have implications for food security. Certain traditional occupations risk being crowded out that could have an effect on the society as a whole.

A study in Kumarakom in Kerala showed that women moved out of agriculture to tourism-linked construction work as it paid them better daily wages. But having neglected the fields, they ended up losing on both counts as the construction work was only short-term but they could not return to cultivate fields overgrown with weeds.

It becomes the prerogative of governments and the industry to ensure that rather than displace them, tourism should build and bolster supplementary livelihood options that women can choose from. The demand for water by hotels can mean less local water for nearby farmers, which can affect food production and increase the workload of women in collecting water from other sources. The establishment of golf courses and special tourism zones or enclaves can also put severe constraints on land and water resources for communities burdening the women the most. The incriminating links between tourism and climate change will unfortunately add to the burden women already bear.

Human Rights ABUSE

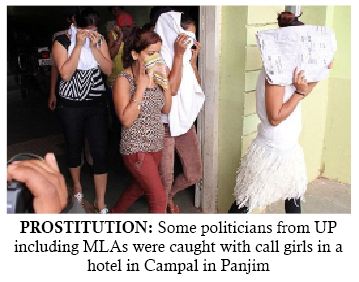

THE gross violation of human rights due to sex tourism and trafficking of women are the shadow side of the booming tourism industry. Migration and trafficking of women, both from within developing countries and cross border to service the tourist trade is commonplace.

Russian women to Thailand and the Philippines and Goa, eastern European women to European countries and women from Nepal and Bangladesh are trafficked to India to service the sex trade. The reports of the Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women (UNCHR) have highlighted the links between countries in economic transition and the increase in trafficking and forced prostitution of women.

Though there are efforts by few tourism service providers to condemn child sex tourism and actively participate in campaigns that combat it, tourism industry bodies have not taken serious action against the exploitation of women in trafficking and sex tourism.

In fact, while tourism is celebrated as a globalised and modernised form of development – it is global tourism, globalised crime and technology like the internet that have also given the sex industry new means of exploiting, marketing and supplying women and children as commodities to buyers.

PORTRAYAL of Women

THE ideological constructs of the advertising industry have infused the tourism, aviation and hospitality industry. In tourism marketing, women are the ‘face’ of the sector, being the most widely-used objects in tourism promotion after natural beauty and cultural heritage. Women have been objectified and depicted as pleasure providers – their images often exoticised, patronising and misleading.

There is also a strong case for eliminating sexual objectification of women working in the tourism industry. With sex tourism being the most negative and prominent example, there is a significant amount of sexual objectification of women working in the tourism industry. Women are expected to dress in an “attractive” manner, to look beautiful (i.e. slim, young, and pretty) and to “play along” with sexual harassment by customers.

Stereotypical and sexist images of women are often part of tourism promotion in brochures and advertisements. Friendly, smiling and pliant women fitting certain standards of attractiveness, attired in traditional costumes, waiting to submissively serve the customer’s every wish is the typical portrayal of women in tourism material.

The industry however has chosen not to be particularly disturbed by this view of women, of seeing it as a gross violation of their dignity and rights, and believes it to be justified in the sale of a product. It is time the global tourism industry takes responsibility for the way women are used in the selling of tourism and also addresses this in its code of ethics.

Tourism modifies local cultural practices in ways that affect men and women differentially. For example, in Kumarakom, increased houseboat tourism severely restricted privacy of local women who used the same backwaters to bathe and to meet with other women socially. When tourism makes products of culture, it tends to commodify women in particular – although both men and women are impacted by the insensitive selling of culture.

Jane Henrici gives an interesting example of women in Peru – “Before the tourists came, when a woman wore flowers in her hair in public, it meant she was available to enter into a dating relationship. Once the tourists arrived they liked to take pictures of the photogenic women wearing flowers. Soon the pressure built for all women in the market to wear flowers – detaching it from its cultural meaning and becoming a pure aesthetic signifier in a touristic frame.”

The Challenges Ahead

THE tourism industry and stewards of tourism development face many serious social and human challenges in the years ahead. The growing links between migration – both voluntary and forced – and tourism needs to take into account the gender dimensions of this global phenomenon.

HIV/AIDS is not only driven by gender inequality but entrenches it. Tourism is increasingly seen to have a role in this entrenchment in its links to trafficking, prostitution and sex tourism. A categorical position condemning the blatant and inhuman exploitation of women in tourism through trafficking and the sex industry is a moral challenge that the global tourism industry needs to respond to.

Declaring that the tourism product will not be promoted at the expense of women’s dignity, respect and rights is the other position that the industry needs to endorse and practice. The increasing trend of promoting tourism in conflict zones and the consequent impacts it has on women who are already battling for survival is another matter of serious concern. Disasters and epidemics have an uneasy relationship with tourism – but gender dimensions are rarely integrated into assistance and reconstruction efforts with the focus being largely on the safety of tourists and revival of tourism infrastructure.

Engendering tourism policy and understanding tourism’s impacts on women will be key steps to combating the feminisation and informalisation of the workforce in tourism, particularly in developing countries. Research that focuses on the gender dimension of this process could lead to policy and interventions that can work to the advantage of women. Most policies today focus on and favour large and medium enterprise in tourism. Shifting the focus to privilege small and micro-enterprise will not only lead to sustainable options, but create more viable spaces for women’s engagement in tourism.

Poverty, and in particular urban poverty, which threatens to be an issue of growing magnitude has deep roots in gender injustice. Tourism often wipes out the existence and means of livelihood of the urban poor in an overt manner while continuing to depend covertly on cheap labour and exploitative relationships in order to flourish.

Ensuring basic protection in terms of social security, access to information and credit and market linkages will be critical to enable larger numbers of women in the informal economy – both in rural and urban areas – to gain from tourism. Women’s engagement to assert their rights as stakeholders in all aspects of tourism development (planning, implementation, participation, ownership and monitoring) is also determined by their informed participation in decision-making spaces. Facilitating an understanding of tourism and its patterns among women would not only enable them to raise questions about the course of tourism development, but also make claims on its outcomes.

Courtesy: Equations

All marketing have stereotype marketing tech. Just shows dearth in intelligent marketing.