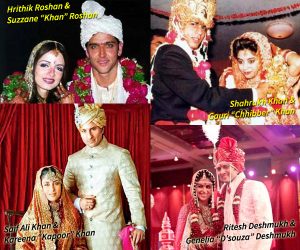

LOVE JIHAD: The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) has been accusing Muslim boys of patoving Hindu girls and even marrying them to convert them into Islam. This has led to many communal clashes

Psychologists suggest that the kind of love that Romeo and Juliet symbolised could be an obsessive compulsive disorder reflected in the many suicides couples commit even now when faced with objections to inter-caste marriages

By Stanton Peele

GENERALLY regarded as the greatest romance in the English language, Romeo and Juliet is actually Shakespeare’s case study of what results when two unformed-maladjusted youths meet at vulnerable points in their lives and are then forcibly separated — addiction, withdrawal, suicide.

The play, of course, ends with the lovers killing themselves. Romeo and Juliet is suffused with death imagery and violence. But, contrary to the popular image that their warring families are the source of this violence, it stems from the lovers themselves, and is directed at themselves.

The play opens with Romeo Montague disconsolate over his lost paramour, Rosaline. He and his friends decide to surreptitiously attend a party thrown by his family’s enemy, Capulet, in hopes of seeing Rosaline. Romeo is not in a good mood — in a word, he is suicidal and expects to “expire the term of a despised life.” Instead, he spies Juliet at the party, with whom he falls in love on the spot.

Note that Romeo goes instantaneously from pathological lovesickness to total infatuation. For her part, please keep in mind that Juliet is a 13-year-old virgin sequestered in her family’s home who has just been told that she is to marry an older man she is to meet for the first time at the party. Instead, she and Romeo exchange a few words and then kiss passionately. Juliet doesn’t yet know if Romeo is married, and if he is, “My grave is like to be my wedding bed.” Not a promising relationship.

Later that night, Romeo sneaks back into the Capulet compound and hears Juliet profess her love for him on her balcony, a sentiment he returns in spades. The two decide then and there to be together forever (“parting is such sweet sorrow”). Romeo immediately rushes to Friar Laurence who is amazed by Romeo’s volatility, but agrees to marry the couple. The marriage follows quickly — the couple has known each other a day (actually, a night)!

Father Laurence is the first therapist in literature (Shakespeare doesn’t do religion). When the good cleric upbraids Romeo for his changeability, Romeo points out, “Thou chid’st me oft for loving Rosaline.” Having read Love and Addiction (just kidding), Father Laurence responds: “For doting, not for loving.” Romeo: “And bad’st me bury love.” Friar Laurence: “Not in a grave, To lay one in, another out to have.” He futilely urges Romeo to go “Wisely and slow; they stumble that run fast.”

Trouble ensues: Romeo’s friend Mercutio fights and is killed by Tybalt, a psychopathic Capulet cousin who is gunning for Romeo. Romeo kills Tybalt. The Prince of Verona banishes Romeo – this before Romeo and Juliet have consummated their marriage! When told there’s bad news, Juliet asks: “Hath Romeo slain himself?” Instead told Romeo is banished, Juliet falls completely to pieces. She is — why depart from character — suicidal: “I’ll to my wedding-bed; And death, not Romeo, take my maidenhead!”

Romeo, of course, expresses similar sentiments:

There is no world without Verona walls,

But purgatory, torture, hell itself.

Hence-banished is banish’d from the world,

And world’s exile is death: then banished,

Is death mis-term’d.

Father Laurence tries cognitive behaviour therapy:

I’ll give thee armour to keep off that word:

Adversity’s sweet milk, philosophy (read “psychology”),

To comfort thee, though thou art banished. . . .

rouse thee, man! thy Juliet is alive,

For whose dear sake thou wast but lately dead;

There art thou happy: Tybalt would kill thee,

But thou slew’st Tybalt; there are thou happy too:

The law that threaten’d death becomes thy friend

And turns it to exile; there art thou happy:

A pack of blessings lights up upon thy back;

Happiness courts thee in her best array.

But then (oy!!!) the good Father resorts to pharmacology: he gives Juliet a potion to make her appear dead. She is taken to the Capulet crypt where Romeo sees her comatose, lies beside her and poisons himself. Juliet awakens and stabs herself. Ah, those headstrong kids!

But, really, was anything else in the cards for this morose, death-destined pair? Don’t blame their self-destruction on love blocked by an unfeeling world — despite Shakespeare’s intoning on their funeral bier,

Where be these enemies? Capulet! Montague!

See, what a scourge is laid upon your hate,

That heaven finds means to kill your joys with love.

That’s not what Shakespeare really thinks about this duo, and what makes him say:

For never was a story of more woe

Than this of Juliet and her Romeo.

He really thinks these kids are sick puppies. And, after all, which is more interesting and worthy of Shakespeare: a play about two lovers kept apart by their obdurate families, or one about two young people driven to death by a detructive egoisme a deux?