SUPERSTITIOUS: Even our scientists who launched the Mangalyaan space craft to Mars took protection by way of poojas to avoid the curse of Mars

Since Modi came to power, astrologers and other quacks are running the government. Even the timing of the launch of satellites and missiles is decided by the stars. An internationally renowned Indian astrophysicist explodes the myths about astrology. Also, if stars have shifted their position in the sky according to NASA, does this change everyone’s stars signs?

By Jayant V. Narlikar

IN THE world of astrology, India has many claims to fame. It has an astrology fundamentally different from both Chinese and Western astrology, possibly more part and full-time astrologers than in the rest of the world put together, and the world’s longest-running English astrological monthly (The Astrological Magazine 1895–2007). Its main government funding agency, the University Grants Commission, provides support for BSc and MSc courses in astrology in Indian universities. And as for the general public, one finds almost universal belief in it.

Indian astronomer and astrology critic Balachandra Rao notes: “The belief in astrology among our masses is so deep that for every trivial decision in their personal lives—like whether to apply for a job or not—they readily rush to the astrologers with their horoscopes.” Likewise, many will consult an astrologer to ensure their marriage date will be auspicious. In 1963, the astrologer’s advice, for example, led to a postponement of the wedding of the Crown Prince of Sikkim by a year. A day seen as generally auspicious can thus lead to a large number of weddings taking place, putting severe pressure on facilities like wedding halls, caterers, etc.

Prediction of Events

WESTERN astrologers are generally taught that astrology is non-fatalistic and therefore not a good bet for predicting events. Indian astrologers hold the opposite view, and every astrologer worthy of the name must be able to make such forecasts. Unfortunately, these predictions do not carry any controls. For example, B.V. Raman (1912–1998), publisher-editor of The Astrological Magazine, wrote that “when Saturn was in Aries in 1939 England had to declare war against Germany” (note the fatalism) in a work intended “to present a case for astrology”. However, this reasoning fails to notice that Saturn was also in Aries in 1909 and 1968 when nothing much happened other than overseas state visits by Edward VII and Elizabeth II, respectively.

Indian astrologers often make extreme claims about Indian astronomy, as when The Astrological Magazine for March 1984 claimed Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto had been discovered around 500 BC. But their claims about Indian astrology tend to be even more extreme, as in the August 25, 2003, Indian Express wherein Raj Baldev, who claimed to be “an authority on the subject of Astronomy, Astrology, Cosmo-Mathematics and Metaphysics” said that ancient Hindu astrology “is a complete science” where even one million billionth of a second “makes a lot of difference.” Sceptics might wonder at this, since it implies that the shadows cast on ancient sundials were routinely positioned to better accuracy than a hundred millionth of the diameter of an atom. Even at night. Can we believe it?

Complexity without End

INDIAN astrology is more complex than Western astrology, with countless authoritative aphorisms to cover every possible situation. Indeed, the few Western authors who have described it for Western use have typically required decades of study before proceeding. But as one of them has noted: “This is of course natural for a society over 6,000 years old whose elders have not only employed astrology but embraced it”.

And there is no Western equivalent to the ways in which those authoritative aphorisms can be modified via suitably chosen amulets, mantras, colours, gemstones (yellow or blue sapphire is said to strengthen Jupiter or Saturn, respectively), and by performing yajnas (a spiritual ceremony involving offerings to fire performed by a Hindu priest). Ironically these modifications specified by the astrologer are essentially fatalistic ways of achieving non-fatalistic outcomes.

Indian horoscopes are a different shape from Western horoscopes, and their signs, houses, and aspects are calculated differently. They also differ in how they are interpreted. A Western-style interpretation focusing on the owner’s personality and motivations would be rejected in India, where clients expect fortune-telling.

Miraculous Nadis

INDIAN nadi astrology has many variations, but if any of them worked it would be a miracle. Nadi astrologers, when approached by a client, are found to have a huge collection of horoscopes on ancient palm leaves, one of which turns out to be the client’s. But a little thinking shows that it is not as miraculous as it may seem. Consider the following scenario.

After providing birth details during the first visit, the client is asked to return a few days later on the pretext that it will take time to find his horoscope among the thousands held by the astrologer. While the client is away, the astrologer, based on the information supplied by the client, writes his or her horoscope on a fresh palm leaf and soaks it in a slurry of coconut kernels and mango bark, both of which are rich in tannin. This gives the palm leaf an ancient look. During the second visit the client is appropriately impressed that his/her horoscope turned up after so many centuries.

Electronic Destinies

IN 1984, the first companies to offer computerized horoscopes appeared in India, 17 years after they had started business in Europe. In 20 minutes (today, in just a few seconds) they could do the calculations that previously took three months. A computer horoscope may cost `25 (about 50 cents) for an ordinary one and `50 (about $1) for a longer one, more in big cities or air-conditioned centres. Predictions cost up to `500 depending on the number of years ahead. Many websites offer free horoscopes.

As in the West, Indian astrologers immediately complained that the computer was devoid of intuition and experience, and did not meet their clients’ need to talk and vent their feelings. Indeed, about two decades ago an educated young man committed suicide after a computer horoscope predicted total failure in everything he did. Nevertheless, as in the West, computer horoscopes seem here to stay.

In 1989, I was showing a visitor around my newly established astronomy centre in Pune. At that time we had just set up our new computer and I explained its capabilities to the visitor. At the end, I waited for any questions she may have had. Yes, she did have a question: “Does this computer cast horoscopes?”

The Ultimate Accolade

THE lobby for Indian astrology had its crowning glory when, in February 2001, the University Grants Commission (UGC) decided to provide funds for BSc and MSc courses in astrology at Indian universities. Its circular stated: “There is urgent need to rejuvenate the science of Vedic Astrology in India . . . and to provide opportunities to get this important science exported to the world.” Actually, the phrase Vedic astrology is an oxymoron since the prefix Vedic has nothing to do with the Vedas, the ancient and sacred literature of the Hindus, which do not mention astrology. In fact, scholars agree that the usual planetary astrology came to India with the Greeks who had visited India since Alexander’s campaign in the third century BC.

Within nine months of the UGC’s announcement, 45 of India’s 200 universities had applied for the UGC grants of `1.5 million (about $30,000) to establish departments of astrology. Of these, 20 were accepted. To those Indians who believe that astrological considerations influence the course of their business and family lives—and this category involves leaders of major political parties—the UGC’s decision might seem sensible if overdue.

But the decision provoked outrage among India’s academics, especially those in the science faculties. More than 100 scientists and 300 social scientists wrote in protest to the government. Of the 30 letters-to-the-editor that appeared in the Indian science journal Current Science, most of them from scientists in university departments or research institutes, about half dismissed astrology as a pseudoscience, and a quarter felt that decisive tests were needed. Against this, the rest felt there was nothing wrong with funding something that most Indian people believe in. But the protests were without effect because, in Indian law, Vedic astrology is seen as a scientific discipline.

Nevertheless, in 2004, several scientists asked the Andhra Pradesh High Court to stop the UGC from funding courses in Vedic astrology because it was a pseudoscience, it would impose Hindu beliefs on the education system, and it would reduce the funds available for genuine scientific research. However, the court dismissed their case on the grounds that it was not correct for a court to interfere with a UGC decision that did not violate Indian law.

In 2011, an appeal under the act that bans false advertising was made to the Mumbai High Court. It was dismissed by the court arguing that the act “does not cover astrology and related sciences. Astrology is a trusted science and is being practiced for over 4000 years…” (as reported in The Times of India February 3, 2011).

Failed Predictions

TO JUSTIFY calling it a science, astrology must fulfil the basic requirement of a scientific theory—it must make testable and correct predictions. Here the performance of astrology in predicting the results of events has been very poor. The nearest we have are follow-ups to predictions of public events such as elections, where failure is the norm. For example, the elections in 1971 were a showdown between Indira Gandhi and her political opponents. The Astrological Magazine was filled with predictions by amateurs and professionals, most of whom predicted that Gandhi would lose. In fact, she won with an overwhelming majority.

The 1980 elections attracted another frenzy of predictions, most of which saw Gandhi losing. For example B.V. Raman, in a rare departure from his usual vagueness, predicted that Gandhi’s efforts to regain office “may misfire. Her ability to influence the Government will be disconcertingly limited in effectiveness” and the outcome “may not see a stable Government.” An Indian horary astrologer (one who answers questions by constructing a horoscope for the exact time at which the question was received and understood by the astrologer) predicted that Gandhi “can never become the prime minister.” However, she won with a huge majority, was prime minister, and formed a very stable government.

Also in 1980, at a large international conference organised by the Indian Astrologers Federation, both the president and secretary of the Federation predicted a war with Pakistan in 1982, which India would win, and a world war between 1982 and 1984. All wrong! These examples and many more are given by Rao, who notes that no astrologer predicted Gandhi’s assassination in 1984, and that the golden rule seems to be “predict only those things which please the listener’s ego”.

Lack of Criticism

IN THE West, books critical of astrology are not hard to find, but in India the reverse is true. Some excellent books exist, such as Premanand et al. (1993) and Rao (2000), but all are hampered by a lack of Indian tests with which to counter true believers. Even Current Science had to wait until Manoj Komath’s (2009) review, which drew heavily on Western sources such as the critical but user-friendly www.astrology-and-science.com. Unfortunately, given the low level of income and high level of illiteracy of the masses, web sources may not be very effective in general.

UGC’s funding of astrology might have been justifiable had Indian astrology ever been a source of new knowledge, or if its modus operandi had been verified by controlled tests. But unlike astrology in the West, where several hundred controlled tests have found no support commensurate with its claims, astrology in India had hitherto been without controlled tests, even though its focus on predicting yes/no events would make testing easy.

I will now describe a controlled test that my colleagues and I conducted recently.

Our Experiment

OUR experiment was performed in the university city of Pune (formerly Poona) about 160 km (100 miles) southeast of Mumbai (formerly Bombay) in the state of Maharashtra, which is the second-largest in population and third-largest in area of India’s states. Pune itself has a population of about 3.5 million.

For the experiment I was assisted by Professor Sudhakar Kunte from the Department of Statistics at Pune University, Narendra Dabholkar from the Committee for the Eradication of Superstitions, and Prakash Ghatpande a former professional astrologer who has subsequently turned into a critic of astrology.

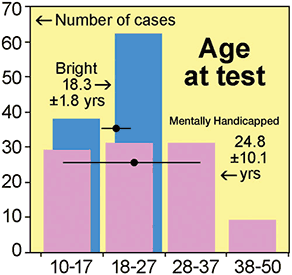

Indian astrologers claim that they are able to tell intelligence from a person’s horoscope. So volunteers from the Committee for the Eradication of Superstitions went to different schools and collected the names of teenage school children rated by their teachers as mentally bright. They also collected names from special schools for the mentally handicapped. The destinies of these cases could hardly be more different, so they were ideal for testing the above claim. From the collected data we selected 100 bright and 100 mentally handicapped cases whose age distribution is shown on the next page.

Birth details were obtained from their parents because birth certificates are rare in India. Professional Indian astrologers routinely assume that birth details provided by parents are correct, so our procedure followed the norm. Each horoscope (birth chart) was calculated by Prakash Ghatpande using commercial astrological software. All horoscopes were coded and stored in safe custody by Professor Kunte at Pune University, so that neither the experimenters (our group of four) nor the astrologers could know the identities of the individuals.

Publicity

WE ANNOUNCED our experiment at a press conference in Pune May 12, 2008, and invited practicing astrologers to take part. We explained that each participant would be given 40 horoscopes drawn at random from our set of 200 and would have to judge whether their owners were mentally bright or handicapped. We also invited established astrological organizations to take part, for which they would be given all 200 horoscopes, a respectably large sample size.

The press conference, which was reported in almost all local and regional newspapers, proved to be an efficient way to reach astrologers. Within a few days we received about 150 telephone calls from astrologers all over Maharashtra expressing interest. We asked them to send us their names, experience, and method of prediction used, together with a stamped self-addressed envelope for mailing the 40 horoscopes. They were then allowed one month for making their judgments. In due course, 51 astrologers asked for horoscopes, of which 27 from all over Maharashtra sent back their judgments. The rest did not tell us why they chose not to participate.

Objections

ASTROLOGERS from the Pune and Maharashtra astrological societies expressed concern that, because the data had been collected by sceptics, the experiment would be biased. We assured them that the scepticism of data collectors had no active role in running the experiment, and that the experiment was of the double-blind kind to make sure it was entirely fair. But they were not convinced, and tried (unsuccessfully) to dissuade other astrologers from participating.

A month later, at a Pune astrological seminar, we explained that tests, indeed many tests, are necessary if astrology is to establish itself as a science. The organiser then said he could provide a set of 10 rules that would tell whether a horoscope’s owner was mentally bright or handicapped, and urged the astrologers present to participate in our experiment.

In India, leading astrologers have their own astrological organisations, and so we wrote to those on our list (about a dozen) inviting them to judge all 200 horoscopes. Two responded with expressions of interest, of which one sent in its judgment. The other remained silent.

An Interesting Sub-Test

ALTHOUGH the Maharashtra Astrological Society had urged astrologers to boycott our experiment, its president kept meeting with us. Among other things he gave us a rule for predicting sex and another rule for predicting intelligence, both of which he claimed were correct in 60 per cent of cases. But when applied to our set of 200 horoscopes, the predictions were respectively 47 and 50 per cent correct, which offers no advantage over pure guessing or tossing a coin.

Results of Our Main Test

OF THE 27 astrologers who participated, not all provided personal details, but 15 were hobbyists, eight were professionals, nine had up to 10 years of experience, and 17 had more than 10 years of experience. So they clearly formed a competent group. Their average experience was 14 years.

If the astrologers could tell intelligence from a person’s horoscope, they would score close to 40 hits out of 40. In fact the highest score was of 24 hits by a single astrologer followed by 22 hits (by two astrologers). The remaining 24 astrologers all scored 20 hits or less, including one professional astrologer who found 37 intelligent and three undecided (so none were mentally handicapped!), of which 17 were correct. The average for all 27 astrologers was 17.25 hits, less than the 20 expected by chance (e.g., coin tossing) and well within the difference of ± 3.16 needed to be statistically significant at p=0.05. So much for the benefits of their average 14 years of experience! Certainly no scientific theory would survive such a poor success rate!

The institution whose team of astrologers had judged all 200 horoscopes got 102 hits, of which 51 were bright and 51 were mentally handicapped, so their judgments were, again, no better than tossing a coin.

Tragically, our statistician, Sudhakar Kunte, died in an accident in 2011, and the security he imposed on data storage has so far made it difficult for us to perform further tests, such as whether the astrologers agreed on their judgments, whether they could pick high IQ better than low, and whether the three astrological methods used (Nirayan, Sayan, and Krishnamurty) differed in success rate. We hope that the access to this data will eventually be possible.

Only two tests of Western astrologers have involved the judgment of intelligence. In Clark (1961) 20 astrologers averaged 72 per cent hits for 10 cases of high IQ paired with cerebral palsy, but this famous result could not be replicated by Joseph (1975), where 23 astrologers averaged only 53 per cent hits for 10 cases of high IQ when paired with the severely mentally handicapped. In any case the sampling error associated with N=10 is more than enough to explain both results, which is consistent with the dozens of other tests that have been made of Western astrology (Dean 2007). It is also consistent with the few tests of Western astrologers who practice Vedic astrology, for example Dudley (1995).

Conclusion

OUR experiment with 27 Indian astrologers judging 40 horoscopes each, and a team of astrologers judging 200 horoscopes, showed that none were able to tell bright children from mentally handicapped children better than chance. Our results contradict the claims of Indian astrologers and are consistent with the many tests of Western astrologers. In summary, our results are firmly against Indian astrology being considered as a science.

IN RECENT years you may have heard that your sun sign has changed, thanks to NASA. Looking online you will find quite a few articles about this NASA “news” here and there; there’s one on Yahoo that has the headline, “Your Astrological Sign Just Changed, Thanks To NASA”. The first paragraph alone is burdened with quite a few scientific errors: “We don’t want to be dramatic, but NASA just ruined our lives. For the first time in 3,000 years, they’ve decided to update the astrological signs. This means that the majority of us are about to experience a total identity crisis. Apparently, these changes are due to the fact that the constellations are not in the same position in the sky that they once were, and the star signs are about a month off now, as a result. To further confuse things, there is now a new, 13th sign, called Ophiuchus, which those born between November 29 and December 17 are lucky enough to have to learn to pronounce.”

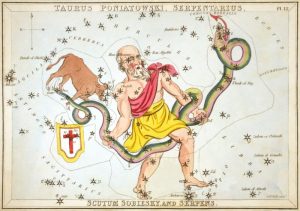

The thing is, there are more than 12 constellations the sun can pass through. Some are smaller, or have fainter stars, so they get ignored. The biggest is Ophiuchus, the serpent-bearer, which is a huge constellation taking up quite a bit of celestial real estate, and in fact the sun spends more time in Ophiuchus than Scorpius. Scorpius has brighter stars and an obvious scorpion-like shape, so it gets better press.

So no, NASA didn’t add in Ophiuchus or change the zodiac or anything like that. Ophiuchus has been around this whole time, but has been ignored by astrologers.

Worse, there aren’t really 13 zodiacal constellations. By some counts, there are as many as 21. Not only that, but Earth wobbles like a top, very slowly, and over centuries that changes the dates the sun is in a given constellation. If you were born in late March in ancient Greece, you would have been an Aries. Today, you’d be a Pisces.

This new agitation started, apparently, due to an article on a NASA site for kids called SpacePlace. It has simple explanations written at a level for children to understand, and it’s fun and accurate.

The SpacePlace article, ‘Constellations and the Calendar’, has been around a while but was updated in January 2016, which may have caught some astrology believer’s eye. The article – well worth your time to read – talks about how the zodiac constellations are defined, and how, over time, they’ve changed (as described above). Apparently, someone didn’t read it very carefully, or didn’t understand it, and wrote that NASA had changed the zodiac.

Here’s an interesting bit of clarification between astronomy and astrology. Some astrologers claim that while the actual constellations HAVE shifted over the ages, Western astrology follows a different system, which uses “artificial” constellations. Rather than following the movement of the visible stars, Western astrology is based on the apparent path of the Sun as seen from our vantage point on earth. Within that path, astrologers have carved out static zones, and they claim to track the planetary movements against these. That is why, according to them, zodiac sign dates remain the same even as the heavens keep shifting.