GOENKARPONN: In 1967 the Loksabha defined Goenkar as an individual who had been born or been resident in Goa on December 20, 1961, the day after the Liberation of Goa

Long before the Goa Forward (GF) party came with the slogan of Goem, Goenkar and Goenkarponn, way back in 1967 the Lok Sabha debated the issue of who qualifies to be called a Goan during the discussion on the Opinion Poll bill

WHEN Goa was liberated, many National Congress (Goa) merged with the Indian National Congress (INC) in 1962. Purushottam Kakodkar was appointed convenor of the newly formed Goa Praadesh Congress Commitee. There was an influx of new members that changed the landscape. A large section of the NC(G)’s top leadership that joined the INC consisted of Hindu Brahmin and upper-caste Catholics. The other castes as a consequence were attracted to the Maharashtrawadi Gomantak Party, which was projected as a Bahujan Samaj or a non-Brahmin Hindu party.

The newly formed MGP and UGP were clear on their stance on Goa’s immediate future. MGP was pro-merger and UGP was pushing for statehood. The Congress was divided—Kakodkar was in favour of maintaining the status quo; a rival group led by Dr. Razma Hedge was in favour of merger. All the parties exploited religious sentiments and the population at large was polarised along communal lines. Ironically both parties saw eye to eye on one point—the need to keep Prohibition out of Goa. (At that time the liquor ban was strictly enforced in Maharashtra.)

Union Defence Minister Y.B Chavan at this time was a strong pro-merger voice. He spoke out several times, even equating the desire for a separate state with sedition. However other Congress leaders like S.K Patil, Lal Bahadur Shashtri and K.K Shah, general secretary of the All India Congress Committee, were all in favour of a status quo in keeping with Prime Minister Nehru’s assurances over the years.

GENERAL ELECTIONS

IN THE first ever general elections of 1963 there were 28 seats at stake for Goa in the Goa, Daman and Diu Legislative Assembly. The MGP was pro-merger, the UGP, against. The Congress manifesto declared that on the merger issue the Government of india would decide Goa’s future according to the wishes of the people of Goa.

JOLT FOR CONGRESS

narrow margin of 30,000 votes, thanks to a sizeable section of Hindus voting against the

merge

THE results were a severe jolt for the Congress. It did not win a single seat in Goa. Prime Minister Nehru reasoned that talk of merger had caused great concern among Catholics, drawing votes to the UGP. Kakodkar found consolation in the fact that the election result proved that the majority of Goans were not in favour of merger as the MGP garnered a total of only about 1,00,000 votes, against the 1,40,000 who voted for candidates from other parties, even though it emerged as the single largest party, winning 14 of the 27 seats it contested. Its allies (Praja Socialist Party members contesting as Independents) won two seats giving it the majority it needed to form the government.

first chief minister of Goa, was the face of merger, he was gracious enough to accept the

results of the Opinion Poll and indeed was re-elected to power in the elections held after the

Opinion Poll

Following the formation of the government by the MGP and its allies, the demand for Goa’s merger reached new heights. Both the Bandodkar government and the Prime Minister’s senior cabinet colleagues from Maharashtra, like Chavan, demanded that the electoral verdict be considered a mandate for merger.

Nehru who stated he was “surprised and pained” at the election outcome, emphasised that “Goa should continue to remain a separate entity” for some more time. He wanted Goa to enjoy freedom in its own affairs and have a legislature of its own and get special grants from the Centre as other union territories did. Interestingly, Nehru termed the results a tie between the pro-merger and anti-merger groups and pointed out, “The MGP secured only 14 seats, but not the majority vote.”

The GPCC was dealt a great blow when Nehru passed away in May 1964. The pro-merger faction managed to convince Shahtri, who had succeeded Nehru, that a fresh mid-term election would decide the question of merger once and for all. Kakodkar rushed to Delhi to persuade Shashtri that the assurance given by Nehru should be honoured, but he was unsuccessful.

Emboldened by this, on January 22, 1965, a merger resolution was moved in the Goa Legislative Assembly. After a debate on the time allotted to speak on the resolution, the Opposition staged a walkout. Thus the lone member to vote against the resolution was the independent MLA from Dui, and the legislature adopted by 15 to 1 the unofficial resolution urging the Government of India to take appropriate steps for merger. The maharashtrawadis were not content with the passing of the resolution in Goa and in less than two months a similar resolution was passed by the Government of Maharashtra.

The Mysore Legislative Assembly reacted to this, and passed a resolution on March 12 and 15, unanimously condemning the Maharastrian move and putting forward Mysore’s own claim, saying “This house is emphatically of the opinion that the people of Goa should have the right to determine their own future”.

It was the Mysore legislature’s stance that, in a sense, focused the attention of the country on a fundamental principle of democracy: that the people of any other state in India were hardly likely to know what was good for Goans.

INDIRA FOR POLL

SHASHTRI’S sudden death at Tashkent on January 11, 1966, was a boost to the anti-merger group. Indira Gandhi became prime minister and Kakodkar, with the support of the GPCC’s new president, Ligorio Cotta Carvalho, took up the matter with her of maintaining the status quo and overturning the decision to hold fresh elections.

It was at Indira Gandhi’s insistence that the Congress Parliamentary Board decided that an Opinion Poll would be held in Goa, as promised by Nehru. It was on Kakodkar’s insistence that Indira Gandhi apparently told Dayanand Bandodkar to resign, to ensure that the opinon poll would be both free and fair. Realising that Indira Gandhi, unlike Shashtri, could not be bullied into holding an election, both the MGP and the Maharashtra leaders accepted her decision to hold the poll.

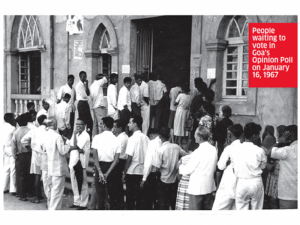

The Goa, Daman and Diu (Opinion Poll) Bill, 1966, was moved on November 30, 1966.

The pro merger group had three demands: (1) Deputationists and non goans temporarily in Goa should not be allowed to participate, (2) Goans living outside Goa should also be given the right to vote in the Opinion Poll, and (3) the Bandodkar Ministry should resign and President’s rule should be imposed.

This led to parliamentary debates that for the first time, concretely discussed the Goan identity and how a Goan can be identified and defined. These debates eventually led to Statehood more than 20 years later.

LOK SABHA DEBATE

PETER Alvares, pro-merger MP elected from Panaji, claimed the demand to merge Goa with Maharashtra was a logical consequence of the political history in India, particularly on the basis of the recommendations of the States Reorganisation Commission that all states should follow the basis of linguistic affinity if they were geographically contiguous to a particular linguistic area. According to Alvares, when Goa was liberated, a Language Commission was appointed under the chairmanship of Amar Nath Jha to determine Goans’ mother tongue for the purpose of education. He claimed that it was found that 72,000 children studied Marathi voluntarily, while only 20 studied in Kanarese (Kannada) and 2,000 in Konkani. This, he felt, made the demand for merger reasonable. He also felt that, as a separate territory, Goa was isolated from the mainstream cultural development in India. Stating that he was part of Goa’s liberation movement for many years, Alvares opined that the movement was spearheaded by a section of people whose leadership was with the national Congress —this despite the fact that the Congress in Goa was opposed to the merger. Alvares felt it was a necessity to conduct the Opinion Poll.

Hanumanthaiya, representative of Bangalore city, stated that the leaders of Maharashtra, more than the people of Goa, were covertly or overtly behind the pro-merger agitation and demanded that a commission be set up to investigate into who sponsored the agitation. He claimed that Dayanand Bandodkar was acting at the behest of the chief minister of Maharashtra. Hanumanthaiya also alleged that the Bandodkar ministry manipulated the voters’ list to include many voters in the list. On the basis of his inquiries, he submitted that the Bandodkar ministry tried to manipulate a decision on the merger of Goa with Maharashtra by opening only Marathi medium schools.

- Dandekar from Gonda supported Hanumanthaiya and stated that there had been considerable pressurisation of a most undesirable kind in favour of a merger. Moreover, the promise that Goans would be given a chance to decide their own future within 10 years after liberation was never kept.

Dandekar argued that a clear-cut definition of ‘True Goans’ after liberation meant those who were notified under the Citizenship Act as persons who would automatically become Indian citizens unless they chose to opt differently. He further read from an order called the Goa, Daman and Diu (Citizenship) Order, 1962, that stated that “Every person who or either of whose parents or any of whose grandparents was born before the twentieth day of December, 1961, in the territories now comprised in the Union Territory of Goa, Daman and Diu shall be deemed to have become a citizen of India on that day.” Taking this fact into consideration, Dandekar submitted that the bill excluded a large number of genuine Goans and included a large number of non-Goans from voting in the Opinion Poll.

According to him, the bill excluded, by the definition of “elector”, those Goans who resided and continue to reside outside Goa and who were always treated as foreigners in the country under the Citizenship Act of 1955 and who became citizens of India only on December 20, 1961 by the Goa, Daman and Diu (Citizenship) Order, 1962. On the other hand, it included a number of people—not Goans by any stretch of imagination—who, particularly after the 1963 elections, moved into Goa to earn a decent living. Dandekar drew the attention of the House to the assurances given by then Prime Minister, Nehru in the Lok Sabha in August, 1964, regarding “some aspects of our basic approach in respect of Goa, when it becomes a part of the Indian Union.” Nehru had clearly specified: “The special circumstances of culture, social and lingual relations and the sense of a territorial group which history has created will be respected… laws and customs, which are part of the social pattern of these areas and which are consistent with fundamental human rights and freedom, will be respected and modifications will be sought only by negotiations and consent.”

Dandekar also quoted president Dr Rajendra Prasad, who said in March, 1962, “We have, however, repeatedly assured the people of Goa and the world that the personality that this area has acquired… shall be preserved.” Dandekar felt that the assurances made to Goans must be honoured as they were a part of the fabric of the honour of the country.

Shinkre of Marmagoa felt it was essential to briefly refer to the background of Goa that consisted of 11 talukas, out of which only four were under foreign domination for 450 years, while the remaining seven which were ceded out or transferred to the Portuguese through treatises with the Raja of Savantwadi and the Raja of Sundhe, were under foreign domination for hardly 150 odd years. Shinkre pointed out that the urge to retain the separate entity of a union territory came from the inhabitants of the four talukas who were the “by-product of foreign domination”, whereas the people in the remaining seven talukas were pro-merger. Shinkre believed that there were only two voices in Goa; one for merger with Maharashtra and the other for a full-fledged state.

Regarding the alleged intolerance of Maharashtra, Shinkre estimated that there were more than 50,000 Goans in Mumbai alone who were agitating against the merger of Goa with Maharashtra and the government of Maharashtra had not attempted to suppress them. Shinkre conceded that Goa was connected to Mysore on three sides, but, irrespective of the political set up, Goans would choose for themselves.

- Chatterjee of the Bundwan constituency clarified that he was not actuated by any animus or any antipathy against Maharashtra, but pointed out certain solemn pledges that the nation had made to the people of Goa. At the Jaipur session, for instance, the Congress had pledged that “the cultural heritage of Goa should be maintained.” Chatterjee also read out excerpts from a letter that Jawaharlal Nehru had written to S. Nijalingappa, chief minister of Mysore in 1962: “We have decided and we hold to that decision that Goa should remain a separate entity in the union of India. Why should there be this hankering for Goa to be merged into this state or that state? I do not understand it. Goa can develop as it likes within the framework of India and add to the richness of India.”

Chatterjee welcomed the constitutional device of a referendum and specified that if people of Goa wanted to remain a separate state in the Indian Union, within the framework of the Constitution, “Let them decide like that. The only thing we want is, let there be an honest effort; let there be a proper and full observance of the pledges”. He argued that the 85,000 Goans who were living in Mumbai played a magnificent part in the liberation struggle of Goa. Chatterjee argued that Alvares was wrong when he pointed out to the Representation of the People Act which says “that an elector can only be a person normally resident in that territory” for the Opinion Poll was not an election for five years of a member to the Assembly or Parliament; it would determine the future of Goa not for generations, but for centuries. Therefore, he opined that all Goans (including 20,000 seamen) should have their say. Chatterjee tabled a motion similar to Dandeker’s that “you should exclude from the poll those who are really not Goans” and cited a letter of the government that said that “Goans are not eligible for enrolment as voters in the electoral rolls for Parliament and Assembly.” But, Chatterjee contended that they “are as much Goans as anybody else. They are sons and grandsons of those who were in Goa” and hence, they should be given a chance of having their say in what shall be the permanent future and reshaping of the destiny of Goa.

Chatterjee moved the first clause,

“Provided that all persons who are not Goans as defined in the Goa, Daman and Diu Citizenship Order of 1962 shall not be eligible to participate in the Opinion Poll notwithstanding the inclusion of their names in the electoral rolls;” and

“Provided that all Goans at present non-resident in Goa as well as Goan seamen on the high seas, who are Goans as defined in the Goa, Daman and Diu Citizenship Order of 1962 shall be eligible to participate in the Opinion Poll”.

Dandeker moved

“Provided that the said electoral rolls shall be amended as follows, firstly, the names of all persons who are not Goans shall be excluded; and secondly, the names of all those persons who are Goans but whose names are not included in the said electoral rolls by reason only of their not being ordinarily resident in Goa, Daman and Diu shall nevertheless be included in the said electoral rolls notwithstanding that they are ordinarily resident in any other part of the territory of India. ‘Goan’ means a person born in Goa, Daman or Diu who become a citizen of India on the 20th day of December, 1961 by virtue of the provision of the Goa, Daman and Diu (Citizenship) Order, 1952.”

- Chatterjee demanded that the amendment moved by him and Dandekar be considered or the Parliament would be guilty of breach of faith.

Alvares objected to the amendments saying that a ‘Goan’ was not defined by any statute or person. Referring to the Goans settled outside Goa, he said that people could not determine the future of Goa in absentia. Moreover, he said that the government of Maharashtra and the Election Commission had accepted that Goans were Indians (this argument was important because Goans in the rest of India were denied the right to vote in the Opinion Poll as they were said to be non-residents. If they were not recognised as Indians by others, they had the right to vote in the only place where they were recognised!). He said, “It is only those Goans, a very large section of them, who refused to call themselves Indian and who insisted upon calling them, Portuguese nationality till the day of liberation, who were not enrolled.“

Dandekar countered this argument by pointing out that, in the general elections of 1952, 1957 and 1962, Goans were excluded from the Indian electoral rolls on the grounds that they were not Indian. He said that when he asked the Election Commissioner why Goans born in Goa but residing in India were expressly excluded for Indian electoral rolls on the ground that they were not Indian citizens, he had received a reply that said in part, “Indian citizenship being an essential requisite for enrolment as an elector, it is likely that may Goans who, although residing in India more or less continuously, had not taken the trouble to take out naturalisation certificates and were not enrolled at the last three general election.”. Hence it was not just mere matter of saying,” I am an Indian citizen”.

Shinkre argued that nothing stopped Goans who were residing in Mumbai or at other places from enrolling themselves in the electoral rolls of Goa after liberation, provided they could prove to the electoral authorities that they were ordinarily residing in Goa.

The amendments by both Chatterjee and Dandekar were put to vote and denied. Vidya Charan Shukla, followed by the chairman, moved that the bill be passed.

The Lok Sabha passed the Bill without accepting any suggestions, except the one asking that Goans residing in other parts of India be allowed to register their names in the voters’ list without a fee.

In this manner, the Bill was thrust upon Goans and non-Goans by the Central government. There were many flaws in the legislation that was enacted to assess the opinion of the people. It was a hurried enactment that was rushed through Parliament with undue haste. Many concerns were dismissed. Goa began walking towards full fledged Statehood that day, but it was a long walk along a thorny path.