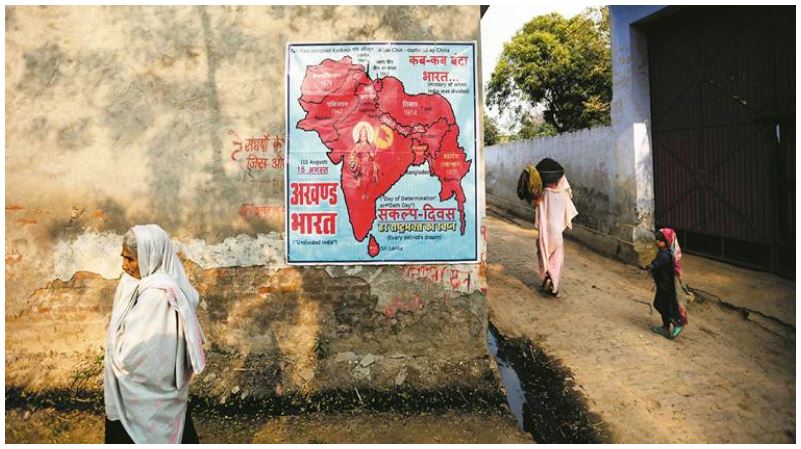

DISTURBING: A map of ‘Akhand Bharat’ outside the house of Bajrang Dal’s Yogeshraj Singh, the prime accused in December 3 violence. The murder and the subsequent lack of action has disheartened the police force further

By Deeptiman Tiwary

Ironically, circle officer SP Sharma, who had investigated the notorious Mohammad Akhlaq lynching on suspicion of storing beef, was murdered by gau rakshaks on December 3, 2018. The top suspects are a mob led by the 25-year-old convenor of the Bajrang Dal in the district, Yogesh Raj Singh. Chief Minister Yogi Aditiyanath’s immediate reaction was to show greater concern over the cows then the death of the officer…

In July 2018, when Circle Officer S P Sharma joined his new posting at Siyana in Bulandshahr district of Uttar Pradesh, Superintendent of Police Pravin Ranjan Singh gave him a list of troubles he was going to face. Top of the list was the Bajrang Dal’s 25-year-old district convenor Yogeshraj Singh. The SP also told his subordinate that this was a problem that was to be “managed”, if not necessarily “solved”.

On December 3, a mob allegedly led by Yogeshraj went after Sharma and two others, who tried to save themselves by locking themselves up in a 10X10 ft room at the Chingrawathi police chowki, about 5 km from Siyana police station. Sharma, 50, had a narrow escape.

Angry over alleged cow slaughter, the mob rained stones and set the chowki on fire. Sharma recalls hearing what sounded like the whistle of an LPG cylinder about to burst after the crowd failed to break open his door. He escaped by breaking through the ventilator of the room.

Within minutes of that attack, the mob had killed Sharma’s subordinate Subodh Kumar Singh, the SHO of Siyana police station — his body found hanging upside down out of his police jeep in nearby fields, a bullet lodged in his head.

As the news of a police officer dying at the hands of a mob, in the latest episode of cow vigilantism in Uttar Pradesh, sent shockwaves, it was also reflective of the circumstances in which police operate in this region, walking the intersecting lines between crime and politics, where problems like Yogeshraj, born of that mingling, must be “managed”.

The son of a farmer from Nayabans village near Siyana, Yogeshraj’s association with Sangh activities began eight years ago. But it was only since Yogi Adityanath came to power that he rose to prominence in Bulandshahr.

A day after the December 3 incident, the Chingrawathi police chowki — about 30 km from Bulandshahr, on the road linking the city to Siyana — wears a forlorn look. A few constables and home guard personnel with 303 rifles mill around inspecting the charred motorcycles and vehicles, and the marks of bricks and stones left on the walls, by the mob.

“I have never felt so scared in my life,” says Chanderpal, a home guard who was locked up in the chowki along with CO Sharma. “I climbed on a steel trunk and with the help of CO sahab broke through the ventilator. We then crawled out one by one,” he says, adding, “Thankfully, the contractor had used bad quality construction material. Or else we would have all died.”

Chanderpal has not eaten or slept for the past two days. “The only thing I could gulp down was a bottle of whiskey last night. I am still terrified.”

Five kilometres away, the Siyana police station is a British-era structure, with a large gate and piles of rotting vehicles impounded by police adjacent to it. After the incident, officers who served here earlier have been summoned to boost the morale. Altaf Ansari, a former in-charge of the station, has been called back from his posting in Ahmedgarh nearby. “The SHO is dead. So Ansari sahab, who served here for eight months in 2017, has been brought. He knows the area and the people,” says Sheeshram, the chief record keeper of the police station.

Subodh Kumar Singh, who spent barely three months at the station, is remembered fondly. Most, including SP Singh and locals, say he was “professional, honest and brave”. His pet dog always kept him company.

Singh was “fearless”, says his driver Ramashray. “He would have survived (that day). When the public was pelting stones, I asked him to jump into the vehicle so I could speed off. But he did not. He kept trying to control the crowd. I ran away. A few

minutes later, I found him in the field lying motionless with wounds in his head. I drove into the fields to try and take him to safety. However, as I put his body inside, the mob attacked us again. I ran to save my life,” he says.

For a police station that has just 12 constables against a sanctioned strength of 60, to manage 32 villages with close to 70,000 people, and 600 FIRs a year, this was a task it was not cut out for. “We were just 15 people at the chowki even after reinforcements arrived from B B Nagar police station (about 12 km away). If we were even 50, this incident would not have happened,” says Chanderpal.

While few call the SHO’s death a conspiracy, and others blame it on politics, some blame it on the poor strength of the force. But most agree that it is unprecedented for an SHO to die in a law and order situation. “Hum toh encounter mein nahin marte (We don’t even die in an encounter),” says a constable with a smirk.

Local BJP leaders and RSS workers have an explanation though for the mob anger. According to them, the SHO had turned a blind eye to cow slaughter and was “interfering in Hindu festivities” and “cultural expression”. “Subodhji is no more, so I do not want to say anything negative about him. But he was not very cooperative when it came to granting permission for Hindu celebrations. He had created a lot of roadblocks for our Janmashtami rally. Following the Mahakali Shobha Yatra he sent notices saying the participants were drunk. So in September, I wrote to our MP about how, due to his interference, the Hindu society was feeling enraged,” says Sanjay Srotiya, the BJP’s Bulandshahr general secretary.

Following the December 3 incident, Meerut Prant chief of VHP Sudarshan Chakra held a press conference vouching for Yogeshraj’s “innocence” and saying he was not at the police chowki at the time of the incident — a claim Yogeshraj has also made in a video on social media. He has also accused SHO Singh of turning a blind eye to cow slaughter.

On Friday, Chief Minister Adityanath said the SHO’s death was not the result of mob lynching but an “accident”.

While UP has seen a series of “encounters” leading to the death of alleged criminals, the BJP government has been facing criticism over law and order. The December 3 incident deals a fresh blow just months ahead of general elections, in a state that will be crucial to how the BJP performs. The party has already stepped up its Ram temple campaign, and posters inviting youth to join a December 7 rally for the same are still up all across Bulandshahr, a district with a substantial Muslim population.

In Yogeshraj’s village Nayabans, Hindus, Muslims are in the ratio of 60:40.

Police sources say much of the “cultural expression” the Sangh leaders accuse the SHO of opposing was “anti-minority”. “Subodhji was experienced. He had worked in Dadri and knew how quickly a communal situation could lead to deaths. He was generally accommodating, but if he saw someone was deliberating trying to disturb peace, he could be quite stern,” says a colleague.

And yet, Yogeshraj, by all accounts “the No. 1 troublemaker of the area”, does not have a single FIR registered against him at the Siyana police station. People did complain, but police always let him off with a warning.

Almost every police officer in Siyana has Yogeshraj’s mobile number. “He is either organising provocative religious rallies or protesting against azaan from mosques. When no issue is at hand, he picks up Facebook posts or even a traffic accident to create trouble,” says an officer from the police station, who doesn’t want to be named. When asked why police dealt with him with kid gloves, senior officers just smile, “You know why.”

Police’s first major brush with Yogeshraj was in late 2016 when he complained that a madrasa in his village, Nayabans, was operating as a mosque and blaring azaan from loudspeakers. Police tried to reason with him, but later took down the loudspeakers, as well as one at the village temple.

In his FIR to Siyana police alleging cow slaughter following the December 3 incident, Yogeshraj has largely named people associated with this madrasa/mosque. He has even said he saw them butchering a cow, a claim not substantiated by eyewitness accounts.

Through 2017, Yogeshraj allegedly organised various provocative rallies. “Earlier, religious processions were taken out only during Holi. In the past couple of years, Yogeshraj and his associates have taken out rallies on every festival.

They brandish swords and guns and shout slogans such as ‘Doodh mangoge to kheer denge, Kashmir mangoge to cheer denge (If you ask for milk, we will give you pudding. If you ask for Kashmir, we will tear you apart)’. What is the relevance of such a slogan on Janmashtami?” asks Habibur Rehman, 60, of Nayabans village.

On January 26, 2018, Yogeshraj took out a Tiranga Yatra through Siyana town. “It was very provocative. There was one Tricolour and the rest were all saffron flags. There were chants of ‘Hindustan mein rehna hai to Jai Shri Ram kehna hai (If you want to stay in Hindustan, must say Jai Shri Ram)’. This prompted Muslims to take out a rally holding the Tiranga,” says an officer from Siyana police station.

Police put up with more. On Janmashtami this year, a constable of Siyana police station shared a morphed photo of Lord Krishna on Facebook. After Yogeshraj sat on a dharna, the constable was suspended. A month earlier, in August, then in-charge of Siyana police station, Bachchu Singh, was summarily transferred, reportedly after a tiff with Yogeshraj. Senior officers though maintain it was a routine transfer. A couple of months before this, Yogeshraj allegedly led a mob that vandalised the Nahar police chowki, about 8 km from Chingrawathi, over a road accident.

When CO Sharma first had an inkling of trouble on December 3, he did what most officers here do. He says he placed a call to Yogeshraj, who was leading the crowd that had gheroaed the Chingrawathi police chowki with a tractor-trolley carrying cow carcasses discovered in the fields nearby.

CO Sharma, who was managing bandobast at the Tablighi Ijtema — a religious congregation of over 10 lakh Muslims near Bulandshahr city, about 40 km away — says he told Yogeshraj, “‘Bhai, please manage your people and don’t let any violence occur. I will get your cow slaughter FIR registered’. He assured me cooperation. When I reached the chowki around 12.45 pm, the FIR had been registered. I took Yogeshraj aside and asked him to remove the vehicle. He agreed and the tractor trolley was even removed briefly. But just then his associates began hurling abuses at him. And then, out of nowhere, the stone-pelting started.”

SHO Singh was already at the spot, and had convinced the villagers to bury the carcasses, before Yogeshraj arrived. “Subodhji asked them to bury the remains and lodge an FIR. At that time there were just 40-50 people. But Yogeshraj and his associates insisted the carcasses be taken to the main road and shown. ‘Photo bhi to khichani hai (One also needs photos)’, they discussed,” says constable Shubham Saini, who was present.

By 1.30 pm, the chowki was gutted and the SHO was dead.

Locals point out how this region has historically never been communally sensitive. Once the bastion of former UP chief minister Kalyan Singh, the area has a significant population of Lodh Rajputs — Yogeshraj being one — along with Jats, Tyagis and Jatavs. Muslims are concentrated in Siyana town and a few villages such as Nayabans. Most of the Hindus are engaged in farming and dairy; Muslims are carpenters, welders or peasants.

In fact the only communal violence that Siyana police station area witnessed was 40 years ago, in 1977. A mosque being built in Nayabans village was demolished by some locals and in the violence that ensued, about half-a-dozen people were killed in police firing. The remains of the mosque still stand while Muslims offer namaz in a makeshift mosque nearby.

Police and locals credit this to the relatively low Muslim population in the area unlike the rest of Bulandshahr district, as well as Siyana’s unique demographic history. The Hindus and Muslims of Siyana — almost equal in number — claim to trace their lineage back to the same family. During the reign of Mughals, two brothers of an influential Tyagi family, Shamsher Singh and Phul Singh, settled in the region and reportedly chose divergent religious paths.

Shamsher Singh embraced Islam, and from his family come most of the Muslims of Siyana. While from Phul Singh’s family come most of the Hindus.

“All Hindus and Muslims in Siyana are Tyagis. We all have the same blood,” says 70-year-old Rifaqat Ali, scion of the Shamsher Singh family. Prem Narayan Tyagi, of the Phul Singh family, agrees: “We remain brothers. Rifaqat and his family is invited for functions of my family. He invites me to his. During our daughters’ weddings we did kanyadaan together.”

Both the men are also influential. While Rifaqat Ali, with a palatial bungalow right opposite the Siyana police station, remains one of the biggest land holders in the area, Prem Narayan runs multiple businesses, including a hospital in Noida. Prem Narayan dabbled in local politics with the BJP earlier and claims his son is closely associated with the RSS.

“It is because of this demography and these two people that there has never been communal tension in the area. Whenever something happens, these two use their influence among people to calm things down. It is only in the past couple of years that we have faced some trouble,” says Inspector Altaf Ansari.

In the year preceding the December 3 incident, SP Singh points out, not a single cow slaughter had been reported in the area. But now, reports are coming in from different villages, with the Siyana police station filing one FIR of alleged cow slaughter, reported in Nayagaon.

As fingers are being raised at the Ijtema gathering, police say they are investigating if the meat of the animals whose carcasses led to the violence was meant for the congregation. Bulandshahr Additional SP told The Sunday Express on Thursday that police would first investigate the carcasses and only then focus on the SHO’s murder.

Says Naresh Tyagi of Nayagaon, “Even Muslims don’t eat beef here. But it appears some Muslims from Siyana have done this for Ijtema.”

Prem Narayan, who had set up a canteen to feed the Ijtema participants, says, “Now I don’t know if beef got cooked in my canteen as well. I don’t check everything. Whatever happened is not good.”

Rifaqat Ali, who knows Prem Narayan arranged the food for the Ijtema, regrets, “This problem has been created… They have been trying to do this for a long time. But we will not let it happen.”

A senior police officer points out that the alleged slaughter could purely be a matter of simple economics, with “so much stray cattle these days”.

Among those struggling to contain the stray cattle menace is Inderpal Singh, the pradhan of Mahav village where the carcasses were found on December 3. He says he is awaiting payments for his sugarcane from the mill to put up a fence around his fields. “The cattle destroy a lot of crops. No one is buying old cattle anymore, so we too leave them. All of this has come together and plunged the entire village in big trouble,” he says.

Late on Wednesday night, as the temperature dropped, policemen manning the Chingrawathi chowki moved into the bus shelter opposite and sat around a bonfire. Since the chowki was gutted, nothing is working inside. The conversation veered around to whether the SHO’s killers would ever be caught. “People must be laughing at us, ‘that they can’t protect themselves what will they do for the public’. You think I will ever be able to face a crowd with the same confidence?” says a constable as the others nod silently.

Courtesy: Indian Express