Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

DALITS PLAY KEY ROLE IN KUMBH MELA!

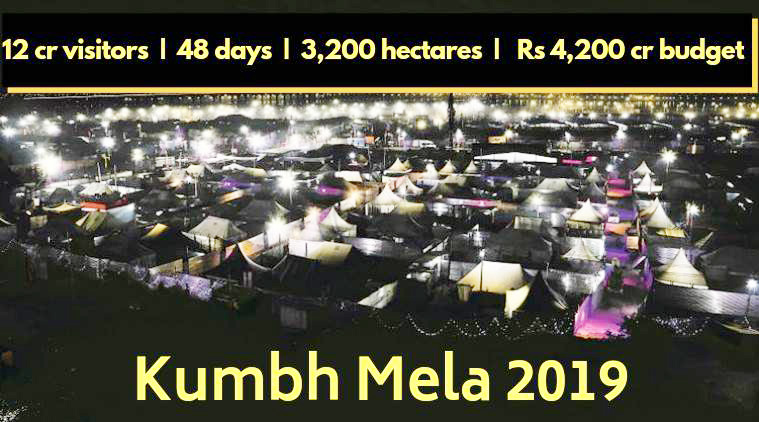

Caste, Jan 26-Feb 01 2019 January 26, 2019EXTRAVAGANZA: One of the tent cities at the Kumbh Mela. There are 1200 such tents besides 5,000 camps across Kumbh. (Photo by Abhinav Saha)

BY SOMYA LAKHANI

Ironically it is the Harijans and Dalits, the lowest classes in Hindutuva society who do the dirty work of cleaning up after holy sadhus and the mostly well-off, upper caste visitors who throng the Kumbh Mela camps to prevent the camps turning into a filthy mess

For three straight days, Ghuriya (50) chewed tobacco, spitting out the red goop only before meals. Young men teased her, Ghuriya’s 10-year-old son imitated her for some laughs, but her husband Heera Lal understood why her mouth was always full; it was to mask the smell.

“Zindagi mein pehli baar aisa kaam kar rahein hain. Pet ne aisa majboor kiya hai (For the first time, we are doing such work. Such is our desperation),” says Ghuriya, minutes after returning to her tent, having finished her eight-hour shift of cleaning nine toilets at the Ardh Kumbh Mela, redesignated Kumbh Mela 2019 by the Uttar Pradesh government.

The Mela began on January 15, and will go on till March 4. “We are expecting a footfall of 12 crore. The number soars massively on Shahi Snaan days. On January 15, the day of the first royal bath, around 1.36 crore people took a dip in the Triveni-Sangam,” says Vijay Kiran Anand, District Magistrate of the Kumbh Mela. That day and the next, the health department says, approximately 200 mt of waste was sent to to the Baswar waste treatment plant in Prayagraj. So far this month till January 18, the plant has received around 1,000 mt of solid waste from the 20 sectors of Kumbh.

An IAS officer, Anand has held charge of the Kumbh Mela for more than a year now.

Anand says they have employed a total of 20,000 sanitation workers — half hired by the Health Department and the rest through outsourced vendors. They include the ‘Swachhta Doot’ keeping clean the 3,200 hectares, divided into 20 sectors, over which the Kumbh Mela is spread, and the cleaners for its 1.2 lakh toilets, such as Ghuriya.

With the Yogi Adityanath government making the Kumbh Mela a prestige project, and tagging it as Swachh Kumbh to fit in with the Centre’s Swachhta campaign, 234 crore of the total budget of4,200 crore has been allocated for sanitation — which includes renting and setting up the portable toilets, buying equipment and disinfectants, paying wages, and providing dustbins and brooms.

At dusk, from the New Yamuna Bridge, one can see the Triveni-Sangam, swathed in saffron on all sides from its vast ‘tent cities’ housing akhadas, devotees, VVIP visitors, and foreign tourists. Some of these are “luxury tents”, put up for the first time, with rates as high as 38,000 a night. Hidden behind these temporary cities, in every sector, are colonies of sanitation workers — spread over uneven land and containing cloth tents covered with used plastic sheets, with paddy spread inside serving as beds. A few have a single bulb inside. Wood, coal and chulhas have been provided for cooking and to keep warm. The workers — from Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Jharkhand — have brought along own utensils and blankets.

It’s here, in Sector 19, that Ghuriya begins her day, in the coldest hour of the night. At 4 am, she heads to one of the 900 toilets in the sector to relieve herself, before returning to prepare a quick meal of aloo-sabzi for her family of five, with vegetables bought from the vendors around, and rice, flour and kerosene got from one of the 160 ration shops set up across the Kumbh by the state government.

At 6 am sharp begins her shift. She dons a blue cap and a thin, sleeveless neon green jacket given by the Health Department — both imprinted with Swachh Kumbh 2019 — over two torn sweaters, before heading out.

It was in early December that a neighbour in Prayagraj’s Sabzi Mandi area told Ghuriya she could get a job at the Mela, earning more than she made selling bamboo baskets. She was told that for three months, her family of five would get a place to stay, food, healthcare, and even an anganwadi for her children, besides350 a day. Her husband and two sons do the same work. While she has visited the Mela several times, this is the first time she is working there. At least 50-plus people from Sabzi Mandi known to Ghuriya are employed with her at the Mela. Via a neighbour, Ghuriya’s family got in touch with Sector 19 ‘site in-charge’ Ankur Sehrawat, a private vendor.

However, Ghuriya claims, “No one told me I had to clean toilets. The thekedar said my husband and I would pick up the flowers devotees put in the river… I cried the first few days. I have never done this before.”

As far as the eye can see at Kumbh, there are tall and narrow blue-and-pink toilets and green urinals — at parking lots, inside tent cities, on the roads, at the bank of the Triveni-Sangam. From 35,000 toilets at the last Kumbh held in then-Allahabad in 2013, to 1.2 lakh toilets now, the difference is telling.

“It’s all maths,” says Dr A K Paliwal, who heads the Kumbh Health Department, which is responsible for the Mela sanitation. The preparation began with Magh Mela 2018 held in Prayagraj. It’s an annual event attracting close to 80 lakh devotees to the Triveni-Sangam over a month. At least 5,000 toilets were installed for the event last January.

“It’s here that we counted the number of users who can comfortably use one toilet. That was around 100. Peak footfall at the Kumbh Mela on days such as Shahi Snaan and Mauni Amavasya is three crore. To manage that we need 1.2 lakh toilets so that there is no open defecation,” says Paliwal.

At the 2013 Kumbh, of the 35,000 toilets, only 5,000 were meant for public and the rest were situated inside akhadas and tent enclosures, he adds. “There was even a space officially marked for open defecation. Can you imagine that today?”

The toilet complexes for men and women are separate, and each complex comprises 10 toilets, with one Western commode for the old and disabled. “Forty per cent of the toilets are for women. We looked for user-friendly toilets, and also structures easier to clean,” says Saloni Goel, Environment and Kumbh Sanitation Consultant. A member of a Union Environment Ministry expert committee and the Central Pollution Control Board, she has been appointed by the state government.

Of the 1.2 lakh toilets, 62,500 community toilets are planned for bus stops, parking lots and the roads, 20,000 of them urinals; while 40,000 ‘institutional’ ones are to be put inside akhadas and tent cities. “We have set up 50,000 of the 62,500 community toilets, 25,000 of the 40,000 institutional toilets, and all 20,000 urinals. The rest will be put closer to the next big day, which is February 4,” says Paliwal.

The toilets at the banks of the Triveni-Sangam have septic tanks attached, so that the waste doesn’t get discharged in the river. Suction vehicles are stationed near the complexes a night before the peak days. “The tanks have a capacity of 10,000 litres each, though our calculations have shown each complex releases 6,000 litres waste daily,” says Paliwal.

Approximately 1,500 swachhgrihis have been deployed only to check open defecation. “They tell visitors about the advantages of using toilets, and also ensure that the toilets in their area are clean,” says Goel, adding that they are meant to give regular feedbacks over electronic devices.

In Sector 19, under the shade of a tree, at least 10 swachhgrihis stand with their ‘Circle Coordinator’, 24-year-old Sandeep Kumar, mapping their next route. Kumar, an M.Com student at Allahabad University, is getting 500 a day for this work. Kumar, who says they work in three shifts, says not all chinks have been worked out. “The device (to give feedback) has not been handed over yet; the app is not functioning properly. So for now, we have WhatsApp groups where we give shift-wise feedback, and also upload photos of dirty toilets.”

No kind of work intimidates him, says Dulichand (28). On the day of the Shahi Snaan though, the street sweeper from UP’s Banda district woke up anxious. “I got the afternoon shift on a day there were crores of people. I kept sweeping for hours — flowers, plastic bags, excreta, wet underwear, paper, jhoothan (leftovers), broken toys, torn clothes. You name it, I picked it,” he says. The area he had to sweep had been demarcated with a chalk, as it is done on all big days.

After sweeping the area for eight hours, Dulichand put the waste in steel dustbins. From there, the tipper vehicle, which does rounds thrice a day, picked up the garbage, and took it to the compactors, which in turn sent the waste to a treatment plant in Baswar, 10 km away.

Says Paliwal, “The length of internal roads within Kumbh is 300 km, so we aimed at a dustbin every 50 metres. At the ghats and Sangam, we put bins every 25 metres. In all, there are 20,000 dustbins.” The bins and 35 lakh garbage bags to line them alone cost approximately5.2 crore.

There are six tipper vehicles in each sector, about 40 compactors in all. Each dustbin weighs 7 kg, and has a capacity of 120 litres.

“While we would have liked to separate the waste into biodegradable and nonbiodegradable, we just don’t have the bandwidth to educate users at the Mela. It requires huge behavioural change and for now, our priority is to ensure garbage is collected,” says Goel.

One major criticism the Health Department has faced is absence of water taps in the toilets. Renu Tripathi (35), a devotee from Kanpur, says she had given up hopes of finding a “theek-thaak (okay)” bathroom on the banks of the Sangam. “I went to at least 15 toilets, either the door doesn’t shut or there is no water or they are just dirty. We heard so much about the arrangements being made this time. What’s the point if I can’t use these toilets?” she asks.

Paliwal says they deliberately didn’t put the taps. “Each toilet has a 1.5 litre bucket, and each complex has a water post from where the user is expected to fill it. We didn’t provide taps for fear of misuse or leakage.”

However, right now not all hands are on the deck. Of the 10,000 total sanitation workers to be hired by the Kumbh Health Department, only 8,000 have joined.

Officials have planned 20,000 sanitation workers and 1.2 lakh toilets to keep this Kumbh, tagged Swachh Kumbh, clean. Of them, 8,000 workers, who have joined duty, have been hired directly by the Health Department of Kumbh. These workers follow a hierarchy which has existed since the colonial period. A group of 12 sanitation workers is called a “gang”, each gang has a “Mate”, who is the supervisor, and a “Mrs Mate”, who prepares the food and takes care of the gang. Over the decades, Mrs Mate has become “Mitaayan”. These gangs are hired by “recruiting jamadaars”, who are paid 325/day and100 as token money or “shagun”. “Earlier there were more than 30 recruiting jamadaars, now there are 12-13,” says a Health Department official.

The other criticism is the shortage of masks or gloves. Ghuriya, who fears she is getting addicted to tobacco in her middle age because of the work at the Mela, says, “They have not given us masks, gloves or boots. All the training I ever got was how to use the jet spray machine to clean the toilet.”

Chunni Lal, 30, a Swachhta Doot, says that a day before the Shahi Snaan on January 15, he picked up some human excreta with bare hands. This is the first time he’s been employed at the Kumbh. “Back home, I do odd jobs; sometimes I return home with no money. This, at least, guarantees, employment for three months,” he says. If toilet cleaners get 350 a day, sweepers like Lal get295 a day, enough to draw him to the Mela from Banda district.

In another corner on the banks of the Triveni-Sangam, Mahesh Kumar (18) says, “I met some sweepers from another sector who had jackets and boots on. For now, I use my hands.”

Sector 19 in-charge, Sehrawat, denies proper equipment hasn’t been provided. He says of his allotted 1,000 masks and 200 pairs of gloves, he has distributed many to the 270 sanitation workers under him.

Adds Paliwal, “We purchased 10,000 masks, 10,000 pairs of gloves and 10,000 raincoats for the sanitation workers. Some refuse to wear them saying they feel ‘restless’ in masks or that they can’t hold the broom properly with gloves on.”

Metres away from the sanitation colony in Sector 19 is a colourful board attached to a tin entrance of a temporary structure. It’s a primary school for the children of sanitation workers, set up by the state government. Some days, the class is full, on others barely seven children show up. The Education Department has set up five such primary schools as well as five anganwadis across the Kumbh, with government teachers taking classes.

“A se anaar, B se…” says Rakhi (6), before running to hide behind her grandfather Sitaram, to avoid being asked to finish “B se…” The 50-year-old street sweeper from UP’s Panna district is standing in the queue of a ration shop. Sanitation workers and kalpavasis (devotees spending a month) are allowed 3 kg flour and 2 kg rice per month at subsidised rates across the 160 ration shops.

“I enrolled Rakhi at the Sector 19 school, but now our tent is a kilometre away. She can’t walk here alone, that’s why she’s forgotten ‘B se’,” says Sitaram, who says he came to work at the 2018 Magh Mela too and is yet to be paid wages for 47 days.

The school in Sector 19 functions from 9 am to 4 pm, and children, like Manoj (8), get uniforms, and a meal comprising panjeeri, biscuits and khichdi.

On December 23, Manoj walked home from the school, played with his siblings, and went in only to find their mother had an hour earlier delivered a child at their tent, on her own. It was when they raised an alarm that someone cut the umbilical cord.

Sona, in her late 20s, had given birth to her fourth child. “Next day, the children told the madam in the school about the baby, who rushed here to ask how I was doing. She named him Sangam because that’s where we are,” says Sona, who came from Banda district with her husband on December 15.

In a few days, she will begin cleaning toilets like Bachhi, her husband, while her three young children look after Sangam. “Madam said she informed officials that a baby had been born here. But no one has visited us. We have two old blankets between the five of us. I fear the baby will fall sick, it’s too cold.”

It’s 10 pm now, and Mahesh Kumar is finally returning to his tent near a drain after eight hours sweeping the ghats. After a quick meal, he has some painkillers for bodyache, caused by the cold, he says.

Lying down next to his younger brother, who too is a sweeper, Kumar says, “Dubki toh maar li, par punya toh hum har roz kamaate hain (We took a dip, but by doing this work, we earn blessings daily).”

The Ganga is at least 3 km away.

- Courtesy: Indian Express