Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

RESCUE KHAZANS FROM GREEDY LANDSHARKS

Cover Story, May 11- May 17 2019 May 10, 2019STANDING TALL: Dr Nandkumar Kamat has been a prominent figure in the battle to save Goa’s Khazans for more than 30 years. (In pic — in December 1990, the High Court directed DC Anil Baijal to inspect the Khazans of St Cruz in response to a PIL filed by Dr Kamat)

Well-known Goan veteran activist and assistant professor in microbiology in Goa University, Nandkumar Kamat, spoke about restoring the ecological, economic and agro-entrepreneurial glory of Khazans in Goa at the K D NAIK memorial lecture organized by the Goa Chamber of Commerce and Industries (GCCI) at the Hotel Mandovi on April 30, 2019. He also urged the revival of the salt pan industry…

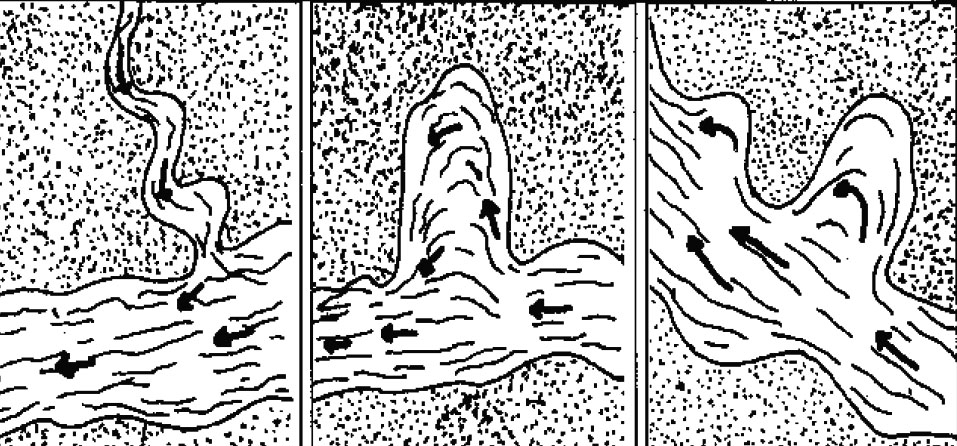

Khazans are reclaimed lands from the river or the sea. A created network of bunds protects the agricultural fields and adjoining villages from tidal flows. Khazan lands have three main features: sluice gate, poim (a depression at the end of the Khazan lands at the lowest level of the low tide) and two types of bunds. Bunds are mini dams fitted with sluice gates called ‘manos’. Khazans are dual purpose. They are used for pisciculture and agriculture, accounting for 50% of rice crop.

What went wrong?

Khazans were traditionally owned by the community. Even before the Portuguese came to rule Goa, consortiums would manage the resources in Khazan lands. These institutions were called gaunkaris (village-association), and had a few farmers managing the system. Under the Portuguese rule, these consortium were renamed comunidades.

Once the laws changed, under the Agricultural Tenancy Act of 1964, the responsibility shifted and maintenance was neglected as landlords were no longer getting the income they used to and tenants were struggling with red tape.

Nowadays farmers prefer pisciculture (fish farming) to paddy cultivation. Their vested interests purposefully do not allow the maintenance of the bunds of the poim. ‘Fake-breaching’ is a common occurrence and bunds are either not maintained properly or water is allowed into the poim with force to gather more land for pisciculture. Of the 18,000 Ha Khazan land, 75% of it is induced with salt water due to lack of maintenance.

What do we lose when a hectare of low lying tidally influenced Khazan land is converted?

As per valuation done by Robert Costanza (a global expert on ecosystem services and valuation) of ecosystem services of 18,000 ha Khazan land, losses due to conversion of Khazan land amount to 25,000-27,000 crore per year — and this is not captured by natural resources accounting in the State.

Why are Khazans valuable?

Khazan ecosystems play an important role in the regulation and maintenance of various ecological processes and life support systems. Khazans serve as barriers to tide, wind and wave action. Khazans also play a vital role in regulation of hydrological flows. Khazan biota, vegetation cover and (soil) biota… helps in water supply functions such as filtering, retention and storage of water. Khazans contribute to soil retention, controlling erosion and facilitating sedimentation. They help to filter suspended sediments from water and stabilize bottom sediments to control erosion. Khazans act as stabilizers and sediment accumulators of the intertidal and subtidal areas of the coast. They act as nutrient sinks, buffering or filtering nutrient and chemical inputs to the coastal environment. Khazan salt pans act as ecological sinks with a potential to transform native bacterial populations to metal-resistant strains corresponding to the dynamic changes in the surrounding metal concentrations. Biota present in Khazan soils helps mineralisation of organic matter in soils and sediments. Khazans contribute to soil formation through accretion of animal and plant organic matter and the release of minerals. Soil formation plays a critical role in maintenance of crop productivity and the integrity and appropriate functioning of earth ecosystems. Khazan flora takes part in biogeochemical cycles such as cycling of carbon, nitrogen and other nutrients. Gas regulation function provided by Khazans help in maintenance of good health of local population and prevention of diseases and in general a clean and inhabitable earth for the global populace.

Employment and business opportunities

In 1992 our panel discovered that 18,000 hectares Khazan lands contribute directly and indirectly 1,15,250 jobs sustainably without input of any state subsidies, infusion of capital, or technology.

a) Rice cultivation in Khazan land

Many seed companies are interested in salt-tolerant genes found in rice strains grown in Khazan land. It’s not easy to put a value on these precious genes. They have evolved through years of adaptation in salinity toleration of wild rice varieties.

Salt tolerant varieties used in Khazan farming: Asgo, Babri, Belo, Chagar, Corguto, Damgo, Dodig, Giresal, Kendal, Kochri, Kusalgo, Patni, Rungo, Shirdi, Sotti, Valai, Xitto.

b) Other cultivation in Khazan land

After the monsoons, vegetables are grown in areas away from the riverine side or from the tidal influences. Dr Kamat has listed micro-irrigated vegetables, which are grown in winter in Khazan lands of some islands in Goa, with their uses and current status. The system of micro-irrigated winter vegetable cultivation is known as ‘Varye ‘.According to Dr Kamat these islands had evolved some rare strains of vegetables suited to saline conditions. These are Amaranthus (Tambdi bhaji) rich in iron, cellulose and fibre; Lagenaria vulgaris (Konkan dudi, bottle gourd) large size and soft texture for medicinal use; Raphanus sativus (mullo, radish) for medicinal value; Coccinia indica (Tendli, Gherkin or ivy gourd) marketed; Hibiscus esculentus (bhendi, okra/lady’s finger) early fruiting variety; Basella alba (Valchi bhaji, climbing spinach) rich in iron, vitamin A; Allium cepa (piao, onion) as a seasoning agent, of medicinal value; Solanum melongena (vainge, brinjal/eggplant; Lens esculenta and Vigna unguiculata (alsando, chovli, moong, different types of lentils) high nutritive value; and Phaseolus aureus, the island variety of green gram, which is now extinct.

c) Salt pans in Khazan land

Agor, mith and agaris — the solar salt production technique is 2000 years old and the salt pans or AGORS are integrated in the Khazan agroecosystem.

In 1876 total 36 villages in 4 talukas of Goa had 386 salt pans and produced 45000 MT salt which was then exported to 15 countries. In 1991 we discovered that 13 villages in 4 talukas had only 119 salt pans left and production had fallen to just 18000 MT

During 1998-99, One ha of salt pan yielded a net profit of 1,50,000 over a working period of 120 days, or a sustainable profit of1,250 per day.

Salt in Goa is pre and probiotic, medicinal living, rich in iodine, microbial pigments, vitamin E. Huge scope exists for using salt pans for production of biofertilisers and seaweeds.

d) Wind and Solar Energy Farms

The linear morphology of Khazan bundhs in eight talukas make these as ideal locations to establish wind and solar energy generation farms due to excellent direct solar energy flux and appreciable wind velocity during seven months of the year.

e)Aquabio entrepreneurship

During 1980s NIO developed the technology of pearl spot/kalundara culture and also crab culture, but despite high demand and premium price there is no organized mass cultivation of either.

f) Alternative Uses

- Cultivation of Spirulina, Algae culture, Petro-algae, etc

Another option is to transform Khazan farms into nutritional factories by mass producing spirulina.

Goa can also replicate the Bangldeshi model of algal culture.

Cultivation of oil-rice Petro-Algae can transform Khazan farms into bio-fuel producers.

The future belongs to new health and nutraceutical products and we need to tap the potential of Khazan land for microbioresources.