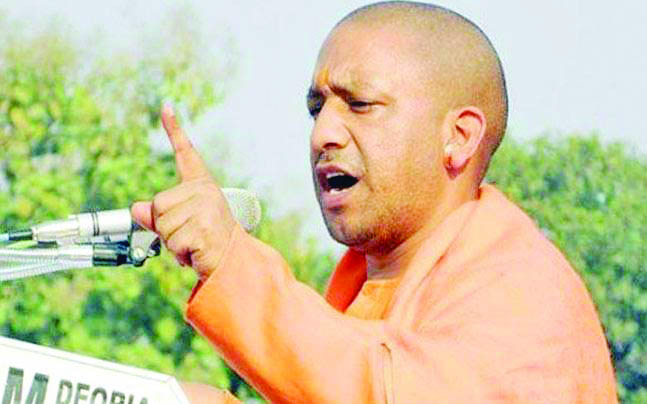

VANDE MATARAM: Yogi Adityanath, controversial chief minister of UP, has declared that anyone who refuses to say Vande Mataram has no right to live in India. This followed the refusal of a prominent Muslim leader to repeat Vande Mataram

By Ritika Chopra

There have been many instances where the members of the EC have disagreed on action to be taken, particularly on hate speech. The EC has been split on what action should be taken against the top leaders of the BJP and their provocative remarks. It seems to be reluctant to take on BJP politicians — particularly Narendra Modi and Amit Shah

While the Election Commission is supposed to transact its business unanimously as far as possible, Commissioner Ashok Lavasa has dissented with the opinion of his colleagues in some recent matters. Under what circumstances did the EC become a multi-member body? What is its procedure when Commissioners disagree? S K Mendiratta, who served with the Election Commission of India for more than 53 years, explains:

Q. When and under what circumstances did the Election Commission of India (ECI) become a three-member body?

Article 324 of the Constitution vests the “superintendence, direction and control of elections” in an Election Commission consisting “of the Chief Election Commissioner and such number of other Election Commissioners, if any, as the President may from time to time fix”.

From the commencement of the Constitution on January 26, 1950 until 1989, the ECI was a single-member body, with only a Chief Election Commissioner (CEC). The ECI was expanded just ahead of the elections to the ninth Lok Sabha, against the backdrop of differences between the Congress government of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and CEC R V S Peri Sastri. These differences began with the Presidential election of 1987. The Union government wanted the nomination process for the election to be timed in such a way that Giani Zail Singh, whose relations with Rajiv were tense, was prevented from throwing his hat in the ring for a second term. But Peri Sastri declined to play ball, and when the time for Lok Sabha elections came two years later, the government, unsure of how he would act, decided to curtail the CEC’s powers by turning the ECI into a multi-member commission.

On October 7, 1989, the government, through a notification issued by President R Venkataraman, created two positions in the ECI in addition to that of the CEC. And on October 16, 1989, Election Commissioners S S Dhanoa and V S Seigell were appointed.

Despite many disagreements between the three Election Commissioners, and the fact that there were no rules governing the transaction of business for the Commission, the Lok Sabha elections of 1989 were conducted successfully. However, the three-member arrangement only lasted for 70 days.

Q. Why did this happen? How did the ECI revert to being a one-member body?

Soon after coming to power, the National Front government of Prime Minister V P Singh rescinded the Presidential notification of October 7, 1989. Dhanoa challenged his removal in the Supreme Court. The court dismissed his petition — but observed that more heads were better than one in a body that had to perform important constitutional functions, and that there should be a provision for transaction of business if the Commission were to be made a multi-member body again.

The Union government then enacted The Chief Election Commissioner and Election Commissioners (Conditions of Service) Act, 1991, which gave the CEC a status equal to that of a Supreme Court judge, and his retirement age was fixed at 65 years. The ECs were given the status of High Court judges, and their retirement age was fixed at 62 years. This meant that if and when the ECI became a multi-member body again, the CEC would act as its chairman, and the ECs would be junior to him. At the time of its enforcement, this Act had no provisions to govern the transaction of the Commission’s business.

For the next two years, the ECI continued to function as a single-member body. Peri Sastri passed away while in office in 1990, and V S Ramadevi was given temporary charge of the Commission until T N Seshan was appointed CEC on December 12, 1990.

Q. What happened thereafter? How did the ECI become a multi-member body again?

Unhappy with Seshan asserting the Commission’s independence, the Congress government headed by P V Narasimha Rao decided to expand the ECI again on October 1, 1993. M S Gill and G V G Krishnamurthy were appointed ECs. Simultaneously, The Chief Election Commissioner and Election Commissioners (Conditions of Service) Act, 1991 was amended by an Ordinance. The name of the law was changed to The Election Commission (Conditions of Service of Election Commissioners and Transaction of Business) Act, 1991. The government made the CEC and the ECs equal by giving all three the status of a Supreme Court judge, retiring at the age of 65 years.

In other words, all three Commissioners now had equal decision-making powers.

Also, a new chapter titled ‘Transaction of Business’, containing Sections 9, 10 and 11, was introduced in the Act. These three sections envisaged that the CEC and the ECs would act in such a manner that there was unanimity in their decision making and, in case there was any difference of opinion on any issue, the majority view would prevail.

Seshan moved the Supreme Court, alleging that the three provisions were an attempt by the government to curtail his powers. A five-judge Bench headed by Chief Justice of India A M Ahmadi dismissed the petition (T N Seshan Chief Election Commissioner vs Union Of India & Ors, July 14, 1995), and the ECI has functioned as a three-member body ever since.

Q. What is the nature of the powers of the Election Commission of India?

In Mohinder Singh Gill & Anr vs The Chief Election Commissioner and Others (December 2, 1977), the Supreme Court ruled that “Article 324, on the face of it, vests vast functions in the Commission, which may be powers or duties, essentially administrative, and marginally, even judicative or legislative”. This means the ECI mainly has administrative functions in the preparation of electoral rolls and conduct of elections. The Commission has to exercise its powers and perform its functions under Article 324 in conformity with the provisions of Sections 9 to 11 of The Election Commission (Conditions of Service of Election Commissioners and Transaction of Business) Act, 1991. The three Sections apply to all the items of business transacted by the Commission — whether administrative, judicative or legislative.

Q. What is the procedure for disposal of matters that come before the Election Commission of India?

Files are normally initiated at the level of the relevant sections/divisions in the Commission’s secretariat, and they move upwards, going up to the Deputy Election Commissioners (DECs) or Directors General (DGs) of the relevant divisions. The DECs/DGs then mark the files needing the Commission’s decisions or directions to the ECs in order of their seniority. With the observations of the ECs, the file ultimately goes to the CEC.

In some cases, where any of the ECs or CEC desire a matter to be discussed in person, that matter is deliberated upon in the meetings of the full Commission, which are normally attended by the concerned DECs and DGs as well. The decisions taken in those meetings are then formally recorded in the file concerned.

Q. What happens if any of the Election Commissioners dissent?

If some difference of opinion persists even after oral deliberations and discussions, such dissent is recorded in the file. All opinions carry equal weight, which means the CEC can be overruled by the two ECs. In normal practice, while communicating the decision of the Commission in executive matters, the majority view is conveyed to the parties concerned. The dissent remains recorded in the file.

In case dissent is to be recorded in a case of judicative nature — for example, in references by the President under Article 103 of the Constitution or by the Governors under Article 192, or in matters relating to splits in recognised national or state political parties under the Symbols Order — the dissenting member may like to record a separate opinion/order. For example, separate opinions were recorded by the two ECs (S Y Quraishi and Navin Chawla) and the CEC (N Gopalaswami) in 2009 in the matter of alleged disqualification of Sonia Gandhi on the conferment of an honour by the government of Belgium.

However, despite the existence of the provision to take decisions by majority since 1993, very rarely has dissent been recorded. When a matter is deliberated upon by the three Commissioners in a Commission meeting, they normally agree to a common course of action. This does not, however, mean that there is no disagreement between the Commissioners — there are certain instances in the past where a consensus could not be arrived at even at the meeting.

Courtesy: Indian Express