Going for the kill: Students at MS University, Baroda, engrossed in a game of PUBG. (Photo: Bhupendra Rana)

By Gaurav Bhatt

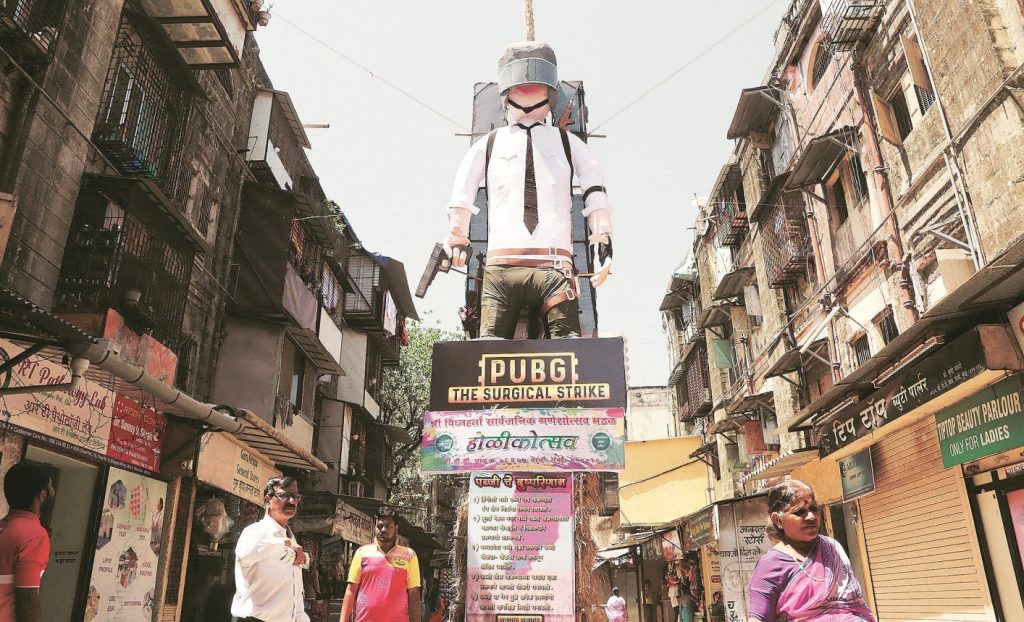

PUBG, an online game which has millions of followers, centres around killing those who disagree with you or whom you do not like. Its popularity in India has increased possibly due to the culture of hate spread by top BJP leaders like Narendra Modi and Amit Shah

She hadn’t played a mobile game before and Veenu Sehrawat wanted to know what the fuss was all about. So, the 17-year-old from Jhajjar, Haryana, downloaded PlayerUnknown’s BattleGrounds on her Moto G 3rd Generation phone this January and went in for the kill. One tap and she was on an island, with 99 other armed players, and all driven by one goal: kill or be killed. Over voice-chat, she could hear them talk, exclaim, cuss. “At first,I had no idea what was happening. But then I killed a guy who had been talking trash. Since then, I have just kept tapping at the screen,” says Sehrawat.

As VTrigger, Sehrawat logs in at least two hours of PUBG daily. She has been caught red-handed by her parents and gotten away by saying it’s “an English-teaching software.” It has helped that her Class XII board results haven’t gone for a toss — she scored 75 per cent — despite not cutting down on game-time with her squad of classmates (she is the only girl playing). “You can be standing in queue at a hospital, or getting bored at a wedding, and you can play a quick round. It’s more than a game. It’s like hanging out with friends or making new ones,” she says.

Lakshya Gaur, though, can’t stop rolling his eyes at his best friend. “His name is Abhishek. But everyone in school now calls him TysonKiller. It’s like they’ve forgotten his name. He has become cool because he gets a lot of kills in PUBG,” says Gaur, a Class IX student at a school in East Delhi, who speaks with disdain not befitting his age. “That is what all the kids in the school talk about now. How they won a match the night before, what guns they like. We even got a note from the school asking us to not play the game,” he says.

Point out that he knows a lot about a game he doesn’t play, and Gaur cackles. “Who said I don’t play? I’m just not very good at it.”

You can find them in parks and metro coaches, hunched over glowing PUBG screens. They are students dodging the teacher’s eye to sneak in a game between classes; or employees stuck to their smartphones during long meetings. If you’re particularly lucky, you might catch a glimpse of Indian cricketers on their tablets and phones at the airports. MS Dhoni and Virat Kohli exchange jibes on who is a better player. Social media banter will tell you that Yuzvendra Chahal rules the roost and Mohammed Shami is laughingly bad.

PUBG (pronounced pub-jee) has invaded urban Indian lexicon, and even crept into pop music. Here is Haryanvi musician Gulzaar Chhaniwala showing you how to tell the real men from the posers. “PUBG mein kill konna kare yaar ne, reality mein vairiyan ne dead kare re (I don’t have any kills in PUBG, I’ve killed my enemies in real life)”.

Mobile gaming has seen hits like Candy Crush and Clash Royale. Even Pokémon GO! had its moment in the sun. But nothing has come close to PUBG’s appeal. The multiplayer game satisfies the primal impulse of gunning down a human-controlled character, as opposed to the AI shooting gallery of single-player shooters. But what has made it accessible and exciting for non-gamers is that there are no bells and whistles. There are no animated cut-scenes or voice-overs. It’s 100 players on an island, scrambling for weapons and fighting to remain the last one standing. What ensues is 30 minutes of shootouts, close shaves, getaways and, at the end, “chicken dinner” for the winners. (A chicken dinner at casinos used to cost as much as a standard bet: $2). It’s like Hunger Games, only you are competing as a solo player (in a 1 vs 99 scenario) or as a team of four taking on 24 other squads.

The game is 999 on computer, and is free to play on mobile. So, a decent phone and good internet connection is all one needs. No wonder, the ascent of PUBG mobile has been in the post Jio-4G India. You neither need to shell out30,000 for the latest generation of gaming console à la PlayStation 4, nor assemble a high-end PC. PUBG mobile’s total downloads crossed 200 million in December 2018 and the number of unique players crossed 120 million users in India, according to market analyst website Sensor Tower.

Saloni Pawar, who goes by the name Meow16K in the gaming and streaming community, misses the “chilled PUBG community” before the game arrived on mobile phones. “I did try playing PUBG mobile a couple of times but I’ve always been a keyboard-and-mouse gamer. But since PUBG mobile’s launch, female participation has definitely gone up. Because everyone owns an Android phone with internet connection,” says the 19-year-old from Mumbai. (“If there’s a female player, people try to protect her or kill her as quickly as possible,” says Sehrawat.)

Mobile manufacturers are cashing in, making the game a benchmark for the latest configurations. The ad blitz has been aggressive (on TV, billboards) and sneaky (keep an eye out for pamphlets plastered on school buses and around school and college campuses.) Streamers (PUBG players who stream their games on YouTube), too, are making hay by promoting products and gadgets to their young audience. Besides, a number of online tournaments, offering 10-100 per kill, provide one more reason to whip out the phone whenever possible.

MONEY FROM PUBG?

Mehul ‘Torpedo’ Dey, a 19-year-old hotel management student and footballer, is now on the payroll of Entity Gaming as the team’s professional PUBG mobile player. “I was never a gamer. I would get annoyed by all my friends, who were suddenly hooked on to this game, but once I tried it, I realised its appeal,” says Dey. “I got so good at it that I decided to form a squad to take part in the Campus Championships last October.”

Organised by developers Tencent Games, it was the first major PUBG mobile competition in India, and saw nearly 2,50,000 registered players. Mehul, along with 79 others, made it to the final round in Bengaluru.

His parents decided to let him compete, and Dey responded by winning the tournament, splitting the `15 lakh prize money with three teammates. “After that, I got to represent India in Dubai, and my parents now know this could be a proper profession. Now, they encourage me. ‘Aaram se khelo,’ they say,” says Dey, who has also started streaming on YouTube.

PRIZE MONEY WORTH 14 CR

According to Varun Bhavnani, a game developer-turned-director of Entity Gaming, one of India’s top eSports outfits, many tournaments are coming up. “Prize money worth 14 crore is up for grabs. We are going to see serious talent from India,” he says.

In March, Naman Mathur, better known as MortaL, and his squad, won30 lakh as prize money at a tournament. The 22-year-old from Mumbai has since taken his YouTube channel from 20,000 subscribers to 2 million by posting tips and recommendations for new players.

That PUBG retains first-timers and non-gamers makes sense, since it was designed by someone who doesn’t consider himself a gamer. In 2017, shortly before his game sold a record 10 million copies in six months, the reclusive Brendan Greene, the titular PlayerUnknown, sat down for a chat with CNET. “For a lot of people, their life is dedicated to gaming. I enjoy games, but I don’t consider myself on that level,” Greene, a former DJ and web designer from Ireland, told the American tech website. “I’ve never played Zelda. I’ve never played these classic games because they don’t interest me,” he said. As a result, perhaps, unlike narrative-driven, single-player affairs, with story missions and boss battles and background music, PUBG is comparatively bare bones. It is a choose-your-own-adventure book with countless endings. There’s no narrative, only the tense stories you and your squad puts together. The battle royale game most resembles a game of roulette. If you lose, you want to play one more round to turn your luck around. If you win, you want to ride it.

Greene, whose gaming days began with the Atari 2600 gaming console in the 1980s, wanted to make a military simulation where “once you die, you’re dead”. He worked on two games with varying degrees of success before striking gold the third time. PUBG had a soft release on PC in July 2017, and frequently saw a million concurrent users.

PUBG’s success also spawned its biggest rival in Fortnite, a game which ditched its initial format to jump on to the battle royale bandwagon. The flashier, more polished Fortnite has since become a pop culture phenomenon, finding admirers in Michelle Obama, rapper Drake, the Fifa World Cup-winning France team and, recently, an on-screen Norse god. But while it conceded ground globally, PUBG hit the motherlode as Greene partnered with Chinese conglomerate Tencent to release the game on mobile in March 2018. Within three days, PUBG mobile reached the No.1 spot in 48 countries, including India.

Ali Vikar from Lal Bazar, Srinagar, was one of the first ones to click download. “I downloaded the game as soon as it was released. But it took me five-six months to find my squad,” says Vikar, a BTech student. “And then it became intense, addictive. Your reflexes, IQ level all come into play,” he says.

Ubaid, 25, who runs the PUBG Kashmir Gameplay channel on YouTube, says the game provides a much-needed diversion. “When I began streaming the games, it used to be just two-three people. Now, our WhatsApp group has grown. I send out an invite at 10 pm, and within minutes we fill the 100 slots,” says Ubaid, who works as a contractor during the day. “I am not a good player. I just like to organise the daily games. But it is only for Kashmiris. We are the children of conflict. Who would have thought a mobile game would help people de-stress and relieve them of anxiety? Even when we can’t visit each other, we are together through PUBG. Koi ladka agar patthar maarta pehle, toh ab vo iss game pe hai. (If a boy would hurl stones before, now he is playing PUBG.) This is the change I have seen,” he says.

For Vikar, who has been a gamer since Class VIII when his parents got him a PC, PUBG is serious business. “My parents get annoyed sometimes. But it isn’t just goofing around. I have no idea what I will do after I complete engineering. When you read about players winning lakhs and making a career, that becomes a goal. Let’s be honest, there are not a lot of jobs in India,” he says.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi earned street cred with teenagers when he name-dropped PUBG at the Pariksha pe Charcha event in January. After a worried parent sought his help to shift the focus of her child from online games to academics, Modi replied: “Ye PUBG waala hai kya?”

INDUCING VIOLENCE?

The parent was not alone. There is legitimate concern over PUBG, a military simulation which uses “real-world” guns and ammunition. In March this year, for instance, police in Rajkot, Gujarat, first announced a ban on the mobile game, concerned by claims that it encouraged young men to violence — and then went ahead and arrested 16 youths for playing or having downloaded the game.

“I had bought the smartphone a year ago. I did play but, of late, I was losing interest. The police detained me simply because I had downloaded it on my phone,” said a 20-year-old civil engineering student in Rajkot. Booked under IPC section 188 (disobedience to order duly promulgated by public servant) and Section 135 of Gujarat Police Act, the students were granted bail the same day. “I might have made a mistake but the police action made me feel that my privacy was being breached,” he says. He no longer plays PUBG on his phone.

Games such as CounterStrike — a first-person shooter pitting counter-terrorists against terrorists — have been a mainstay at hostels and cyber cafes for nearly two decades, but they have never been in the spotlight like PUBG. “A player shooting people virtually is not going to make him pick up a gun. People can differentiate between real life and virtual,” says Vikar, but Ubaid adds a word of caution. “It differs from person to person. Supervision is needed if you are young, or playing it for the first time.”

Bhuj resident Tirth Mehta, medallist at the eSports event at the Asian Games last year, believes such measures will only push youngsters to the game. “Banning anything is never a solution. In Gujarat, people are playing it everywhere,” he says. The game has faced sanctions in countries such as the UAE, Iraq and Nepal. A soft ban existed in Rajkot — the game wasn’t removed from the playstores and no IP ban was implemented — but it was lifted last week.

To their credit, Tencent Games put out a health advisory and introduced time limitations for players younger than 18. But when has a “click no if you’re under 18” alert stopped anybody?

Though the game remains free-to-play and the matches skill-based, meaning one doesn’t need to spend anything to win, in-app purchases offer cosmetic upgrades (clothes, skins for guns, etc are much in demand). “Nobody wants birthday gifts. My classmates tell me, ‘Buy me some in-game cash so that I can buy a new skin for my gun’,” Gaur says. “This is after they’ve pestered their parents to buy a mobile that runs PUBG faster.”

Parents would do well to listen to the PM’s advice. “If we wish that our kids move away from technology, it will be like asking them to go back on progress. Parents should instead take an interest in how children use technology. So the child will understand that whatever I am doing, my parents are going to help me with it,” Modi had said at the event.

But what role should the children play? Gaur shrugs, and makes another precocious observation. “The other day, we were signing scrapbooks, and one question read: ‘What would you take with you to a deserted island?’ Abhishek wrote: ‘99 people and lots of guns’ and added a winking emoji.”

Courtesy: Indian Express