Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

VISHAKA VERDICT IS FLAWED!

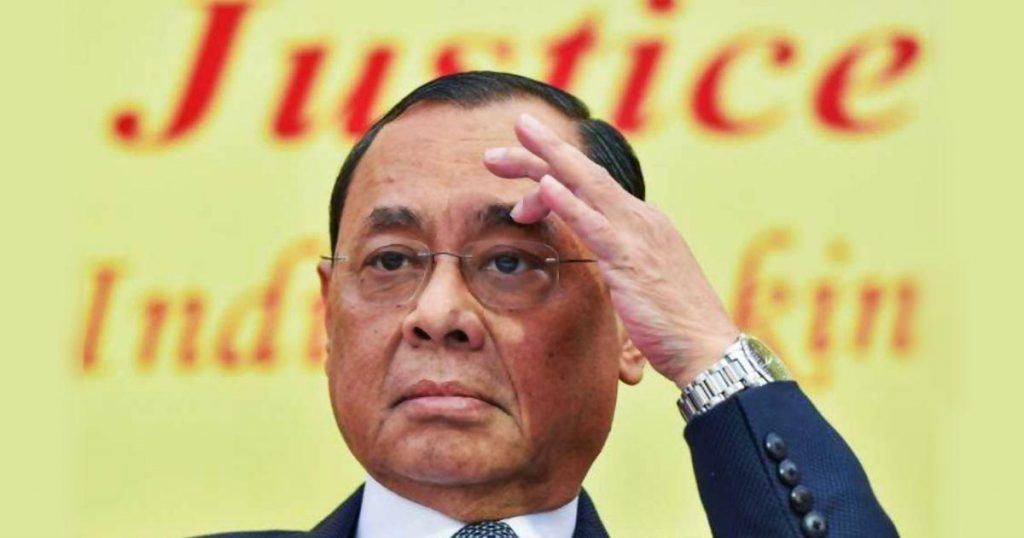

May 25- May 31 2019, PERSPECTIVE May 24, 2019UNFAIR: The Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi has claimed that the Vishaka guidelines and the (Prevention of Sexual Harassment) POSH act does not apply to him. There is no provision in the rules as to what action can be taken against the person holding the highest offices if he indulges in sexual harassment

By Gaurav Bhatt

If a colleague harasses you sexually you can complain to the boss and get him arrested under the laws governing prevention of harassment at the work place. But what do you do if the harasser is the boss himself? Leading women’s lawyer Indira Jaisingh is demanding that the act should be amended to provide for inclusion of everyone including the chief justice of the Supreme Court and even the president and the prime minister

In the aftermath of the allegations against CJI Gogoi, senior advocate Indira Jaising spoke to the Indian Express about the in-house inquiry into the sexual harassment case against CJI, polarisation at the Bar, the need for more SC/ST and women judges in the Supreme Court, and said the appointment of judges should be more transparent.

Q: Last year, after the January 20 press conference by the four Supreme Court judges, you had appreciated how Justice Ranjan Gogoi, along with the others, had spoken about the independence of the judiciary. Why the criticism now?

I believed that history was being made and I wanted to be witness to that history. I cannot analyse it. I would like to ask Justice Gogoi what was that press conference all about? Was it about democracy being in danger? Was it about the institution? Was it about your angst against (former CJI) Dipak Misra? What was it? We supported him because we thought this was about a very, very important institution, the Supreme Court of India… I was present at the Ramnath Goenka Lecture which Justice Gogoi delivered. I was thrilled beyond words to listen to his speech. I said to myself, finally, finally, finally we have a Chief Justice here who is not going to allow curbing of dissent.

Q: Since that January press conference, a lot of what happens inside the courts has become public. How has that shaped the institution?

It should have shaped the institution for the better. There is no solution to anything except sunshine and transparency. And I would have thought that the extent to which the Supreme Court is discussed and written about would only make it improve, and that they would take all the bona fide criticism on board and change themselves. However, it has actually declined. Either they are closing ranks to ward off the criticism… because at the end of the day, what on earth is democracy all about? It’s about the right to question you. I don’t see why I don’t have the right to question the judiciary.

This is the first time I have seen the judiciary been aggressive against a lawyer. It is an attack on right to representation. (On May 8, the Supreme Court issued a notice on a petition seeking direction to the Centre to register an FIR against Jaising, her partner Anand Grover and the NGO Lawyers Collective for alleged violation of rules related to receipt and use of foreign funds.)

Q: Union Finance Minister Arun Jaitley has gone on record to say that when people don’t get a favourable order, they become ‘institutional disruptors’ who say that the court is compromised. Can you name one judgment or any one order where I have said that the institutional integrity has been compromised because a favourable order was not given?

Let me give you the example of Sabarimala. Justice Indu Malhotra gave a dissenting judgment. Go back and read my tweets and see what I said then. When people were pillorying her for giving that order, I said, ‘Look, she is entitled to her opinion’.

Q: But you have been very critical of the judgment in the Judge Loya case.

Is that being compromising of the judiciary? It is being critical of a judgment. Please distinguish between being critical of a judgment and critical of an institution. Make that distinction.

Q: We saw a group of Congress MPs moving an impeachment motion in Parliament against former CJI Dipak Misra. Wasn’t that politics?

You have to understand, impeachment is a political process. It happens in Parliament. It is MPs who decide whether to impeach or not to impeach. (But) yes, politicians can’t decide guilt and innocence. That is why the three people appointed to find the facts are sitting judges of the Supreme Court.

Let me give you an example. There was an impeachment motion against a sitting judge of the Madhya Pradesh High Court on the initiative of a former judicial officer whom he allegedly sexually harassed. That impeachment motion was signed by nearly 60 MPs from across political parties. Hamid Ansari, then vice-president and chairman of the Rajya Sabha, admitted that motion. Supreme Court Judge Justice R Banumathi was appointed to head the committee (in 2015). Attorney General of India K K Venugopal and High Court Judge Justice Manjula Chellur were members of the committee… So that answers your question. Yes, it is a political process and it will continue to be a political process.

Q: You said that the Bar has collapsed. Can you elaborate?

There is polarisation occurring in the Bar. It was in a very recent case when, for the first time in my 50 years at the Bar, I heard a polarised debate inside the courtroom. There was a time when the Bar was united on democratic rights, on the rule of law. It’s no longer united on the rule of law because we have reached a stage where we are easily capable of redefining these concepts. You have a different definition of law, I have a different one. You have a different definition of democracy, I have a different one.

Q: Coming back to the sexual harassment case against the CJI… the complainant had written a letter to 22 judges of the Supreme Court with an affidavit. What could they, the judges, have done with the complaint? What process should they have followed?

They had many options. First of all, the CJI should have completely disassociated himself (from the case). He made, as I said, the original sin of sitting (on the bench that heard the case). After that, there was no fairness in the process. When you sit in court and the court says this is an attempt to destabilise… There could never have been an impartial inquiry because of what he (Gogoi) said.

Q: But when 22 judges get a serious, detailed affidavit…

They could have just forwarded the affidavit to police and said, ‘We don’t know what this is all about. You figure it out.’ You could have had an independent, impartial agency, not connected with the Supreme Court, look into it.

Now, I will tell you what options she had. She was unlawfully sacked. Right? She could have gone to the high court and challenged the termination of her employment. Any court would be obliged to listen to her.

Now, the POSH (Prevention of Sexual Harassment) Act doesn’t apply to judges. They say Vishaka (guidelines) don’t apply to us. Also, focus your attention on the word ‘in-house’. What is in-house? It’s a voluntary inquiry conducted voluntarily by an organisation to inform itself. It’s not a legal process. If I don’t want to, I don’t have to go before your ‘in-house’. I can say well, courts of law are available. I will exercise my remedy in a court of law.

In my opinion, perhaps, they should not have held an in-house inquiry at all. All the 22 judges were part of the full court resolution. They could just do what POSH advises. It says it’s the duty of an employer to assist an employee in taking legal action as she would like. Under the law, an employer is obliged to help the employee file a criminal complaint… Far from performing its duty, the court is doing the opposite. The Supreme Court can help her go to a court of law. The court can provide assistance, the court can provide a lawyer… There’s a lot the court can do.

They should have just said, look, this is something that we cannot inquire into because willy nilly in some way or the other, the institution will get compromised, not an individual judge. So it should be a very participatory process.

If the court wants to do it in-house, in my opinion, the victim should have the option to nominate one person. The court should have the option to nominate one person, and between the two of them, they can nominate a third person. This is done day in and day out in arbitration.

Q: Does it all come down to more accountability, a need for the judicial accountability Bill? The attempt to have a National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) was scuttled.

I was one of those who opposed the NJAC Bill. But my reasons for opposing it were very simple. Where is the transparency? First of all, why is it skewed in favour of the government, which is what the court finally held. But I did also raise the question of transparency. The time has come for appointment of judges to be a transparent process. Let there be a commission, the National Judicial Appointments Commission. Let it be a participatory commission. Let the proceedings be transparent.

Q: After the Supreme Court’s order in the SC/ST Act, you had commented on the ‘Brahmanical nature’ of the judiciary. You have also been very vocal about gender disparity in the judiciary. How can these imbalances be remedied?

See, it’s very easy to have more SC/ST judges. Today the court doesn’t have a single SC or ST judge. So when I made the statement, it was not a false statement. And I was threatened with contempt of court inside the courtroom… But there are no easy solutions. What I think you need are institutional checks and balances. And yes, you need more women, more SC/ST (judges), you need diversity.

Q: Can the complainant appeal the clean chit given to the CJI?

There is a judgment of the Supreme Court saying that this order of the in-house committee is an appealable order and that is the reason a copy has to be given to her. So she can appeal it and have it set aside. That’s their own judgment. That judgment was delivered in the case of the ADJ (Additional District Judge) who had complained of being sexually harassed by a sitting High Court judge. The 2003 case of Indira Jaising vs Union of India was also a case of sexual harassment by a sitting high court judge. So, it’s a problem that they have not been able to resolve since that time. They don’t know how to deal with women. And they don’t know how to deal with sex. It’s as simple as that.

Q: You have said that sexual harassment is endemic within the judiciary. But why has the Bar been silent until now?

The Bar is silent on everything, not only on sexual harassment. The fact that the Supreme Court Bar Association passed a resolution saying that the process adopted by the Supreme Court was wrong came as a pleasant surprise to me. Yet, you see what Mannan Misra, the president of the Bar Council, has said. He says the problem is you have given too many rights to women.

Q: You said seven judges should not hear your case and you cited the doctrine of bias? Isn’t that choosing your Bench?

I am not questioning judicial orders. I am questioning administrative orders. So my argument is, the person who is in charge of passing the administrative order is the accused. He is the master of the roster. He constituted that Bench. There is a solution in law for this. In the Madhya Pradesh case, I argued that when a judge is under inquiry, he is to withdraw from administrative and supervisory work. Now the work of constituting benches is an administrative job. The Chief Justice could not have done the work anymore because he is under inquiry.

Q: So the CJI should have stepped down?

I am not saying step down. Some have gone to the extent of saying that he should remove himself from administrative and judicial work. I wasn’t going that far. I said I will go as far as the Supreme Court has gone. They have said that when a judge is being inquired into, he ceases to do administrative work. Now setting up Benches is administrative work. So I am questioning those administrative orders.

Q: This is not about the judiciary alone. In its present form, the POSH Act seems to offer no solution in cases where the accused is the seniormost person in any organisation. Does this call for a serious relook at the legislation?

In my opinion, the Vishaka judgment is flawed because it doesn’t take these issues into consideration. Every person who comes to me for advice on sexual harassment, I have told them don’t go to the internal committee. It’s a purely voluntary committee. It’s a little complicated… But in the case of the judiciary, there is a law which compels me to go to this committee.

Q: Who do you go to if not the internal committee?

File a civil suit in the nearest magistrate’s court. That’s it. Let the law take its course.

Q: So you are saying that not only in cases where the accused is the seniormost person, but in all cases the complainant should go to court?

In all cases.

Courtesy: Indian Express