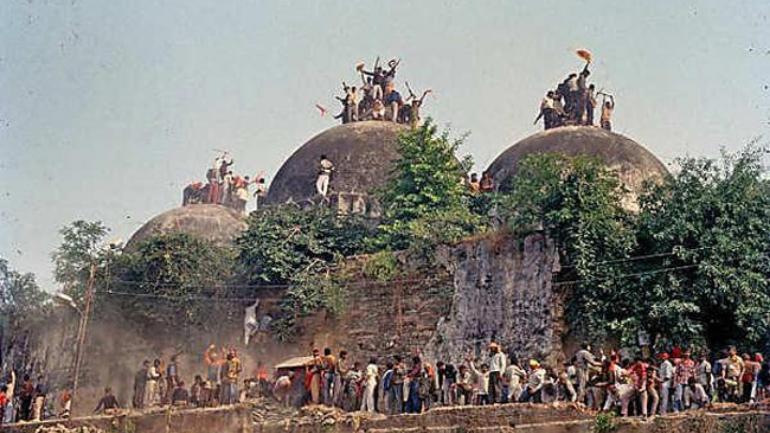

JAI SHREE RAM: The RSS is already making demands for the immediate construction of the Ram Mandir at Ayodhya at the site of the demolished Babri Masjid

By Aakash Joshi

For the RSS the elections are not an end in themselves but merely a means to achieve their dream of a Hindu India where minorities will be second class citizens

Is the cultural nationalism espoused by those that follow the ideologies of V D Savarkar and M S Golwalkar one that has an essential connection to democracy? Or, to ask the more fundamental question, is majoritarian politics at its core democratic?

In his article ‘Election is the ideology’ (Indian Express, May 28), Vinay Sitapati makes a compelling case to answer these questions in the affirmative. Hindu nationalism, he argues, emerges around the same time as the British colonial government first began to provide limited franchise to Indians (with the Government of India Act of 1919), and given that India is a society “composed of groups with identities” rather than one of “individuals with interests”, “the logic of democracy began to be seen through the prism of demographics”.

But democracy is not just about who wins an election. It is, equally, about the sort of public those that seek to rule create, on the road to power.

There is, of course, an intrinsic (even necessary) connection between majoritarianism and democracy — both are based in the ultimate analysis on the legitimacy that winning an election provides. Yet, there is — or ought to be — something more to democratic politics than merely the logic of electoralism. And there certainly is more to Hindutva than winning elections.

Among the Hindu nationalist organisations that emerged in the 1920s, the RSS and its offshoots today hold the greatest sway. The core of the RSS remains, by and large, aloof from electoral politics and like the other ideologically-driven movement that emerged in India in 1925 — the communists — there is a purity of purpose associated with this distance from power. The idea of the Hindu Rashtra is more than just that of a “Hindu vote-bank”. It is a conception of history, nationhood and citizenship that is the antithesis of Sherlock Holmes’ famous dictum — it twists facts to suit theory, rather than theory being determined by facts.

There is, for example, no doubt that the RSS and its subsidiaries have worked tirelessly over the last century to create a Hindu nation from an assortment of castes and tribes. Yet, is the ultimate aim of the Hindu Rashtra merely a vote-bank that encompasses all Indians other than Muslims and Christians? Unlike the Congress, or various other political formations, power is not an end in itself for the Sangh — it is the means to propagate and further a particular kind of society, where individuals are both products of and vehicles for “cultural nationalism”.

Organisationally and ideologically, the separation between the RSS and BJP is telling. The latter has, on the one hand, as Sitapati puts it, “catered to Hindu castes microscopically while painting the Muslim as the broad brushed ‘Other’” and on the other, its discourse has become increasingly intolerant — think “Congress mukt Bharat”, “urban naxal” and, of course, “anti-national”. The ideological core of the Sangh, though, has behaved differently since its political wing attained a majority in the Lok Sabha. Take for example Sarsangchalak Mohan Bhagwat’s statement ahead of the Bihar elections in 2015, calling for a review of reservations at a time when the BJP was doing its best to build alliances across castes. Or the invitation to and then the celebration of former President and Congress stalwart Pranab Mukherjee’s address at a flamboyant RSS function in Nagpur by the top leadership of the Sangh.

Another clear sign of the priorities of the RSS is its disproportionate engagement with the Marxist-Leninist left. Electorally, the communist parties are hardly a challenge to the BJP, except perhaps in Kerala. Yet, academics, universities and intellectuals who are often barely a light shade of pink are accused of being anti-state actors, or alienated from “Bharatiya culture” and holding a “fascistic and dogmatic worldview” (‘Most intolerant of them all’ by Manmohan Vaidya, Indian Express, June 26, 2018). The explanation for this obsession with what is now a minor political force is not, cannot be, electoral. It comes from the desire for a hegemony that is also intellectual, social and cultural.

With political power, this road to dominance is far smoother. It can be done through re-writing textbooks or through pliant vice chancellors. It can use the media, and it can use cinema. It can make freedom fighters of collaborators, patriots of assassins, rewrite history, science and geography, even medicine. But not all it does is with the next election in mind. The project has a timeline that goes far beyond the half-decade cycle.

None of this is to say that the Hindu right is in any sense aloof from political power, or that the Sangh has not been united on the ground in creating arguably the most successful contemporary election-winning machine. But to state that two decisive Lok Sabha wins have completed the millennial project, that “the Hindu Rashtra is here” is premature. That project will continue to fight for dominance in the realm of ideas, food habits, literature, economics, cinema and all the myriad ways in which “cultural nationalism” can be imagined. Equally, for those that wish to oppose such total hegemony, the resistance cannot be limited merely to elections.

Courtesy: Indian Express