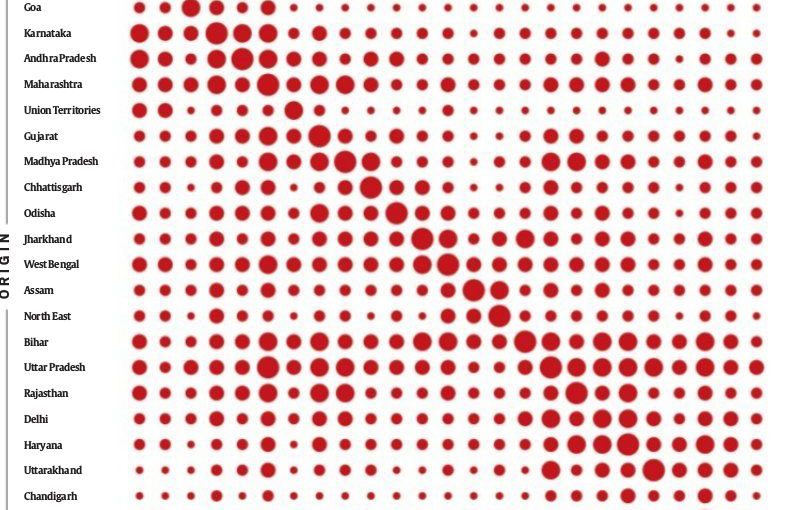

INDIAN STATES: Intra-state migration continued to form the largest share of migration. Almost 11.87 crore of the 14.2 crore migrants (over 83%) between 2001 and 2011 moved within their states. As you can see, Goa received the highest number of migrants from Karnataka, Maharashtra and UP

According to the 2011 census 14.2 crore Indian citizens migrated from poorly governed backward states like UP and Bihar to fast developing cities like Surat and Goa. In the 2021 census you will see the migration gathering momentum with more people from northern states shifting to the more prosperous southern states. Migrants come to Goa for exactly the same reasons that Goans go to London…

In a country with a long and often violent history of sons-of-the-soil politics, migration is a politically fraught issue. From the attacks on south Indians in Mumbai in the 1960s and 70s to the Northeast’s identity debates, and the anxiety over “Bangladeshi influx” in West Bengal to the unsettled row over the National Register of Citizens (NRC), the changing numbers of its people are more than just a figure for a population on the move due to India’s robust economy, while competing for its limited resources.

Amidst a global rise of anti-immigration sentiments, riding on populism, this politics is also up close and central back home now. In West Bengal, the BJP’s allegation against other parties of treating illegal Bangladeshi migrants as a vote bank will gather pitch as it makes a bid for power in the state come 2021, while wielding the NRC as a sledgehammer. In Maharashtra, the BJP’s clever distancing from the Shiv Sena and its anti-migrant rhetoric before the 2014 Assembly elections was directed as much at its vote banks in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, as the migrant settlements in the Pune-Nashik-Mumbai-Thane urban conglomeration.

The gamble paid off, when the BJP, contesting all 60 seats in Mumbai-Thane for the first time, won more seats than the Sena here. Even in national capital Delhi, the tussle between the Aam Aadmi Party and BJP over the Poorvanchali base is no-holds-barred and transparent, partly the reason why the BJP has stuck to Bhojpuri actor-turned-politician Manoj Tiwari as its state chief through thick and thin. The BJP has also used its state satraps strategically, whether it is Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath across the country or Petroleum Minister Dharmendra Pradhan, an Odia, in cities like Surat, with its high number of migrants from the state, in the run-up to the 2017 Assembly elections in Gujarat.

Occasional attacks on migrants — be it north-Indians in Maharashtra or Gujarat, or those from the Northeast in Bengaluru — add fuel to the churn.

But, how much of this is supported by the latest data on migration released by the Census of India?

BROAD TRENDS

Slow, steady, mostly intra-state

- In 2011, for which the figures are available now (that is, nearly a decade ago), 38% of India’s total population were migrants. Or, 45.6 crore people in the country had moved residence — intra-district, inter-district or inter-state — over the years.

This number was a massive jump from the Census before that, in 2001, despite the decadal population growth in the same time of about 18%. In 2001, the migrant numbers stood at about 30.5% of the population. In other words, this means that between the two Census, India saw about 14.2 crore people migrating — a jump of almost 45% from the migrant numbers seen between Census 1991 and 2001, when about 9.8 crore left their homes for new places.

Given that the 1991-2001 growth in migrant numbers from the decade before that (1981-1991) was only 27%, another story emerges from these numbers: that the effect of the economic reforms of 1991 started reflecting after a decade. - Intra-state migration continued to form the largest share of migration. Almost 11.87 crore of the 14.2 crore migrants (over 83%) between 2001 and 2011 moved within their states.

However, again, both the intra-state and inter-state numbers were robust when compared to 1991-2001. If the inter-state number stood at 1.7 crore in Census 2001, it was 2.19 crore in Census 2011 — a gain of 29% in the second decade after economic reforms (again, more than the population growth of 18% in that period). - The numbers also showed migration rising, whether rural to rural, rural to urban, urban to rural or urban to urban. Given the already high base, the rise in rural to rural was modest (21%) compared to urban-to-urban movement, which more than doubled (114%).

STATE TRENDS

UP, Bihar lead the way

- At least 12 major states — Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Odisha, Kerala, Assam, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Jammu & Kashmir and Jharkhand — saw net migration out of the state (more people left than came in between 2001-2011).

UP (-34.34 lakh) and Bihar (-27.26 lakh) sent the largest numbers of migrants to other states. Rajasthan (-3.7 lakh), West Bengal (-2.9 lakh), Odisha (-2.8 lakh), Madhya Pradesh (-2.7 lakh), (undivided) Andhra Pradesh

(-2.2 lakh), Kerala (-1.9 lakh) and Assam (-1.5 lakh) also saw large numbers leaving.

The numbers also showed that the pace of people leaving Bihar grew faster than in UP, when compared to 1991-2001. However, in the 2001 Census as well, Uttar Pradesh (-26.9 lakh) and Bihar (-17.2 lakh) topped the states with the largest number of migrants to other states. - Among states receiving migrants, Maharashtra stood at the top, with net numbers of 24.42 lakh (people who came in minus those who left). But Gujarat saw the biggest rise (+13.75 lakh against +6.8lakh in 1991-2001). As the BJP would point out, Narendra Modi was the Chief Minister of the state (2001-14) in the decade that saw that rise. After Gujarat, people flocked to Haryana (7.8 lakh), Karnataka (5.55 lakh) and Punjab (4.86 lakh).

Meanwhile, the net addition of migrants seemed to have moderated in Delhi (+14.96 lakh against +17.6 lakh in the previous Census).

CITY TRENDS

Mumbai sees a fall, Delhi tiny rise

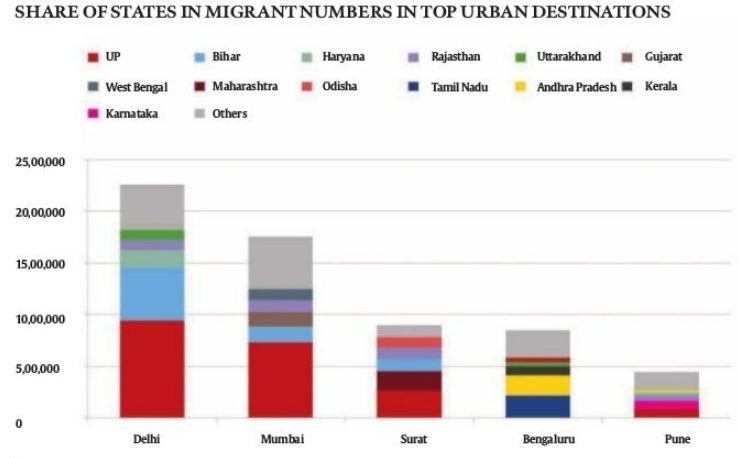

- Major urban centres saw significant reshuffling in the 2001-2011 decade, with people streaming in from rural and other urban centres. Among them, reflecting the draw of Gujarat, the industrial city of Surat (8.94 lakh migrants) emerged as as the third-largest migrant destination. The top two were Delhi (22.5 lakh) and Greater Mumbai (17.53 lakh). While Greater Bangalore (8.4 lakh migrants) and Pune (4.4 lakh) rounded up the top five, Kolkata (3.7 lakh), Gurgaon (3.2 lakh), Ahmedabad (2.87 lakh), Ghaziabad (2.8 lakh), Chandigarh (2.2 lakh), Chennai (2.1 lakh) and Hyderabad (1.68 lakh) remained the other major destinations for migrants.

However, despite what politicians would have you believe, the migration into Greater Mumbai slowed between 2001 and 2011, from the previous decade (24.9 lakh migrants), while Delhi gained only marginally. At the same time, the rise in migration levels in Gurgaon and Ghaziabad suggests the traction commanded by the National Capital Region as a magnet for migrants.

Bengaluru’s rise matched the emergence of the city as a hub for Information Technology and other knowledge-sector economies in the first decade of the 21st century. - The numbers also reflected another change from 1991-2001, when Chennai, with about 4.3 lakh people coming in, was the third largest migrant destination. Now it stood at 11th position.

- Politicians appear to have been the first to spot this shift. In Delhi, they have zeroed in on the fact that almost two-thirds of its migrants (64) came from UP or Bihar between 2001 and 2011; and in Mumbai, on the fact that the two states accounted for almost 50% (8.7 lakh) of its new residents during that period. In Tamil Nadu, meanwhile, which once would burn at the suggestion of a “Hindi imposition”, identity politics has been largely on the wane, though the BJP wave may have sent some ripples.

‘REASON’ TRENDS

Jobs on top, in a post-1991 economy

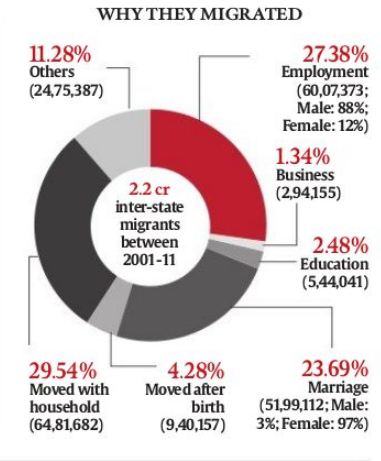

- Among women migrants, marriage was the overriding reason to move within the state in 2001-11. For the men, this was work/employment and education. When it came to inter-state, the difference was starker: while over 97% of those who migrated to another state due to marriage were women, over 88% who did so due to work/employment were men.

In terms of overall population, 27.38% gave work/employment as the reason to migrate inter-state during 2001-11, while over 23.69% cited marriage. Inter-state, the largest chunk (29.54%) moved with their households, while only 2.48% gave education and just 1.34% business as reasons.

The migration trends ran parallel to the changes in Indian economy after the 1991 reforms. India’s economy grew from Rs 5,31,814 crore (at current prices) in 1991 to Rs 20,00,743 crore in 2000-01, before leaping to Rs 72,48,860 crore in 2010-11 under the new series. During this period, the population jumped from 84.6 crore (Census 1991) to 102.87 crore (2001) and then 121.1 crore in the last Census (2011). The birth rate (per 1000 population) moderated from 29.5 (1991) to 25.4 (2001) to 21.8, and life expectancy jumped from 58.7 (1991) to 62.5 (2001) to 67 years — an improvement of over 14% during the two decades. Overall, while the decadal population growth stood at 21.54% for 1991-2001, it moderated to 17.72% by Census 2011.

These demographic changes were accompanied by a leapfrogging economy and a substantial change in the nature of it. According to data maintained by the erstwhile Planning Commission, the share of agriculture and allied sectors (at constant 2004-05 prices) declined from 29.53% (1990-91) to 22.3% (2000-01) to 14.6% (2010-11). Basically, the share of agriculture, the mainstay of the rural economy, in the total GDP had shrunk by half by the end of the second decade after economic reforms.

Agriculture Ministry statistics reveal that, at the same time, the proportion of agricultural labour compared to cultivators in the rural economy rose (40.3% in 1991 to 54.9% in 2011). Since agricultural labour offers seasonal employment, this meant more workers migrating looking for work.

Courtesy: Indian Express