NOBEL WINNERS: Rewarded for finding models to fight global poverty (l to r) Michael Kremer, Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee

By Udit Misra

The Nobel prize-winner for Economics shared by an American of Indian origin, Abhijit Banerji and his wife Esther Duflo have created modules for fighting global poverty…

The research conducted by this year’s Laureates has considerably improved our ability to fight global poverty,” the Nobel citation says. “Their new experiment-based approach has transformed development economics.”

The 2019 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel has been awarded jointly to Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer “for their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty”. The award carries a purse of 9 million Swedish krona (about ` 6.5 crore) to be shared among the three winners.

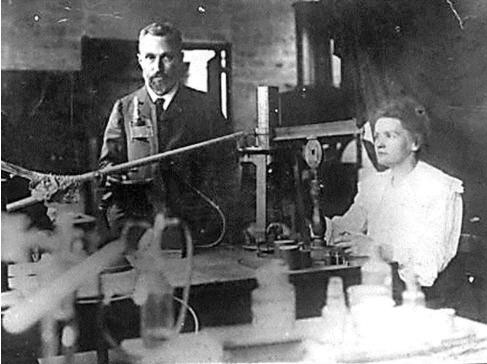

When asked what she would do with the “considerable” prize money given that most of her work is on alleviating poverty, Duflo recalled Marie Curie, who had bought a gram of radium with the prize money from her first Nobel (in Physics in 1903): “We will discuss and decide what our ‘gram of radium’ is.”

Like Curie, who won the 1903 Nobel with her husband Pierre, Duflo is married to Banerjee, with whom she shares the honour in part. They have been collaborating for long, and in 2011 wrote the book Poor Economics: Rethinking Poverty and The Ways to End it together. The couple are at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Kremer is at Harvard University.

Why have Banerjee, Duflo, and Kremer won the Nobel Prize?

“The research conducted by this year’s Laureates has considerably improved our ability to fight global poverty,” the Nobel citation says. “Their new experiment-based approach has transformed development economics.”

In Poor Economics, Banerjee and Duflo bemoaned how the debates on poverty “tend to be fixated on the ‘big questions’: What is the ultimate cause of poverty? How much faith should we place in free markets? Is democracy good for the poor? Does foreign aid have a role to play? And so on”.

Banerjee, Duflo and Kremer, who have been working together since the mid 1990s, are different in that they do not get stuck with the “big questions”. Instead, they break down a problem, study its different aspects, conduct various experiments and, based on such “evidence”, decide what needs to be done.

Thus, instead of looking for the silver bullet to prop up the 700 million people globally who still live in extreme poverty, they look at the various dimensions of poverty — poor health, inadequate education, etc. They then drill down further on each of these components. Within poor health, for instance, they look at nutrition, provisioning of medicines, and vaccination, etc. Within vaccinations, they try to ascertain “what works” and “why”.

As Duflo said immediately after the announcement: “People have reduced the poor to caricatures without understanding the roots of their problems. We decided let’s try to unpack the problem and analyse each component scientifically and rigorously.”

How does this approach work in practice?

“The lack of a grand universal answer might sound vaguely disappointing, but in fact it is exactly what a policy maker should want to know — not that there are a million ways that the poor are trapped but that there are a few key factors that create the trap, and that alleviating those particular problems could set them free and point them toward a virtuous cycle of increasing wealth and investment,” Banerjee and Duflo said in Poor Economics.

Breaking down the poverty problem and focussing on the smaller issues such as “how best to fix diarrhoea or dengue” yielded some very surprising results.

For instance, it is often believed that many poor countries (like India) do not have the resources to adequately provide education, and that this resource crunch is the reason why school-going children do not learn more. But their field experiments showed that lack of resources is not the primary problem.

In fact, studies showed that neither providing more textbooks nor free school meals improved learning outcomes. Instead, as was brought out in schools in Mumbai and Vadodara, the biggest problem is that teaching is not sufficiently adapted to the pupils’ needs. In other words, providing teaching assistants to the weakest students was a far more effective way of improving education in the short to medium term.

Similarly, on tackling teacher absenteeism, what worked better was to employ them on short-term contracts (which could be extended if they showed good results) instead of having fewer students per “permanent” teacher, in order to reduce the burden on teachers and incentivise them to teach.

And what is their “new experiment-based” approach?

The “new, powerful tool” employed by the Laureates is the use of Randomised Control Trials (or RCTs). So if one wanted to understand whether providing a mobile vaccination van and/or a sack of grains would incentivise villagers to vaccinate their kids, then under an RCT, village households would be divided into four groups.

Group A would be provided with a mobile vaccination van facility, Group B would be given a sack of foodgrains, Group C would get both, and Group D would get neither. Households would be chosen at random to ensure there was no bias, and that any difference in vaccination levels was essentially because of the “intervention”.

Group D is called the “control” group while others are called “treatment” groups. Such an experiment would not only show whether a policy initiative works, but would also provide a measure of the difference it brings about.

It would also show what happens when more than one initiatives are combined. This would help policymakers to have the evidence before they choose a policy.

Is there a flip side to RCTs?

The use of RCTs as the provider of “hard” and incontrovertible evidence has been questioned by many leading economists — none more so than Angus Deaton, the winner of the Economics Nobel in 2015, who said “randomisation does not equalise two groups”, and warned against over-reliance on RCTs to frame policies.

While randomly assigning people or households makes it likely that the groups are equivalent, randomisation “cannot guarantee” it. That’s because one group may perform differently from the other, not because of the “treatment” that it has been given, but because it has more women or more educated people in it.

More fundamentally, RCTs do not guarantee if something that worked in Kerala will work in Bihar, or if something that worked for a small group will also work at scale.

This Nobel, albeit indirectly, for RCTs will likely stoke this debate again.

Courtesy: Indian Express

Other married laureate couples