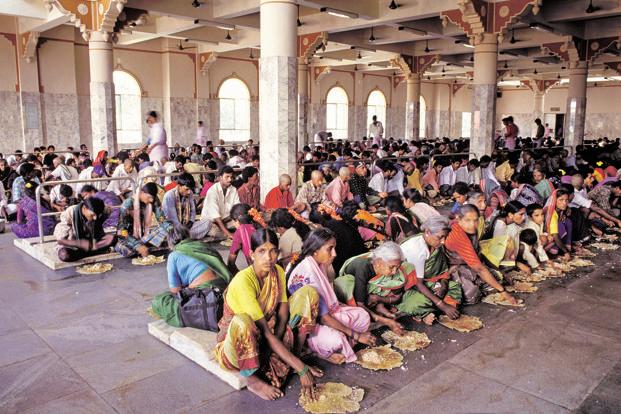

GIVING: India has the potential to become a global philanthropic powerhouse. A report has found that most people in India — 84% of the 836 million adults — give at least once a year

By PR Sanjai

Philanthropy does not mean just feeding the poor. It means making the poor independent so that they can feed themselves as Azim Premji, Sudha Murthi and Shiv Nadar have dramatised…

Athaazha Pazhnikaarundo (Is there anyone left without supper)?” This was the question that every feudal landlord in Kerala used to ask before closing their main gates every night.

These landlords have long vanished from Kerala, thanks to land reforms by the then Communist party chief minister EMS Namboodiripad.

“As agriculture took a backseat, you will not find landlords checking whether anybody is starving in the night. Indeed, giving back is deeply ingrained in the fabric of Indian culture,” says Ananthanarayanan Achuthan, a Malayalam teacher from Thiruvananthapuram, who researches Kerala history.

For India, philanthropy is not a new phenomenon. The culture of philanthropy is as old as India itself, which has a history spanning thousands of years. One who enjoys abundance without sharing with others is indeed a thief, says the Bhagavad Gita, a 700-verse Hindu scripture that is part of the Mahabharata. There are many who continue to imbibe these values even though the India of today may bear little resemblance to the civilization described in these ancient texts.

Take the case of Suhasini Mistry, a poor domestic help who set up a charitable hospital called Humanity Hospital in Hanspukur, Joka, West Bengal.

At 23, Mistry lost her husband and had to fend for herself and her four children. Her husband died because they could not afford proper medical treatment. The memory stayed with Mistry, and she decided to try and help people who may face similar difficulties.

She did a host of odd jobs from cleaning dishes to selling vegetables, and managed to save `20,000, while educating her son Ajoy Mistry to become a doctor with the help of some philanthropists. In 1996, with the help of some locals and her savings, she set up a small hospital, working out of a hut. Today, the hospital is run under the umbrella of Humanity Trust.

Examples of philanthropy across different segments of the society aren’t difficult to find. For Akshay Saxena and Krishna Ramkumar, both Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) alumni, it was a choice between helping the underprivileged and working at a high-paying corporate job. They chose the former after realizing that economically disadvantaged students did not have enough opportunities to access resources for higher studies.

The duo founded Avanti Fellows, which mentors high school students and works with them to prepare them for higher education. They draw on their network, comprising IIT engineers and students from other private engineering colleges, who in turn work with the underprivileged children.

“Charity and philanthropy has been in the ethos of the Indian traditions. Individuals and religious institutions have been contributing to the welfare of the poor since antiquity. Alms giving, offering food, and giving zakat, the Muslim tradition of giving, are some of the forms of charity motivated by Indian religious beliefs,” says Vidya Shah, chief executive officer at EdelGive Foundation, a unit of Edelweiss Group.

She notes that there are similarities and differences in the ways of giving in India and the rest of the world.

“Indian traditions in the middle ages witnessed movements to donate land, labour and succour to the needy, which was not reflected so strongly in the ways of giving by the world,” she says.

Shah adds that it’s not just individuals, but also the business community which has been contributing to social and economic development from times dating back to the 19th century.

The first known Indian endowment, the JN Tata Endowment Scheme, was founded in 1892 and remains the foundation for the Tata Group’s philanthropic activities. Jamsetji Tata was considered on a par with the UK’s Joseph Rowntree and Scottish American industrialist Andrew Carnegie in pioneering the concept of building wealth for public good.

Tata was one of a number of Indian business leaders engaged in philanthropy in the early days of industrialization.

“On a personal front, one may do philanthropy based on instinct. But organizations do it differently, by looking at long-term sustainability for instance,” said Shankar Venkateswaran, chief, Tata Sustainability Group at Tata Sons Ltd.

Venkateswaran adds that corporate philanthropy is now becoming more structured, particularly after the government’s directive to companies to spend a part of their profits on corporate social responsibility (CSR).

“If you go back to history, there were hardly any differences between the company and the owner. The promoters did not see themselves as different from the companies they founded. So the owner’s philanthropic activities were typically done through the company and neither the owner nor the public saw anything odd about that,” said Venkateswaran.

According to the new companies law, corporations need to spend 2% of their last three years’ average profits on CSR activities starting the current fiscal.

Venkateswaran said that at present, philanthropy has become more about management than giving.

“Seeking regular reports and poring over them is a good thing but it cannot substitute going to the field and seeing things for yourself,” he adds.

Less than a third of Indians give to registered charitable organizations, even though more than 80% give overall, according to a major study of giving across India. It found only 27% of people gave to a registered charitable organization.

The November 2012 India Giving Report by Charities Aid Foundation (CAF) found that philanthropy in India has the potential to soar in the next decade, with more than half a billion people giving for religious and charitable reasons each year.

The study, based on interviews with nearly 9,000 people from across the country, found India has the potential to become a global philanthropic powerhouse. Overall the report found that most people in India—84% of the 836 million adults—give at least once a year.

What is needed, though, is a widening of the community of givers, say experts.

“Kerala landlords are no more checking whether there are starving population. Obviously, nobody would want a starving or needy population to be there waiting for your help,” says Achuthan. “What we need is a bunch of philanthropists who will ensure equality in the society by creating equal opportunities.”

Courtesy: Livemint