Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

Palliative Care in India: The Need of the Hour

Life & Living, Nov 16- Nov 22 2019 November 15, 2019By M A Muckaden

Palliative medicine in India:

The need for palliative care in India is estimated to be around 175-275 per 100,000 of the national population for India and is classified by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as a “high” palliative care requirement region of the world. The current health care spending in India is 4% of the gross domestic product (GDP). There is no allocated budgetary provision for palliative care, even though World Health Assembly has declared that palliative care should be an integral part of general health care in every country. Thus, 80-85% of patients must spend out of their own pocket for their health-related expenses; most related to aggressive medical interventions in the last few days of life. This definitely can be avoided if there is universal access to palliative care.

Definition of palliative care:

Palliative care is defined by WHO as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification, impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems: physical, psychosocial and spiritual.” National Comprehensive Cancer Network in its guidelines,emphasises the importance of assessing family needs, values, beliefs and cultures.

Goals of palliative care:

As patients’ have largely incurable illnesses, palliative care focuses on:-

providing relief from pain and other distressing symptoms;

affirming life and regards dying as a normal process;

intending to neither hasten nor postpone death;

integrating the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care;

offering a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death;

offering a support system to help the family cope during the patient’s illness and in their bereavement;

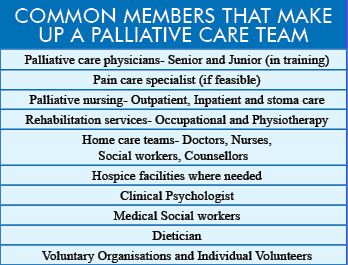

using a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families, including bereavement counseling, if indicated;

enhancing the quality of life, and may also positively influence the course of illness;

Palliative care is applicable early in the course of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and includes those investigations needed to better understand and manage distressing clinical complications.

It is also applicable to patients of all ages and all chronic life-limiting conditions which include cancers, respiratory, cardiac, neurological, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other diseases. Needless to say, the care could be needed for many years.

Quality of life and holistic care:

Palliative care is holistic, and person-centred with the primary aim of improving quality of life for these patients and their primary care givers, by adding ‘life to days rather than days to life’

The five most common physical symptoms at presentation are fatigue, pain, lack of energy, weakness and loss of appetite; in more than 50% of the patients. Weight loss occurs significantly more often closer to the end of life. The other common symptoms are nausea, vomiting, constipation, and dyspnoea. Management includes medications, preferably by the oral route; round the clock to achieve a steady state in the blood stream, and in rational combinations to promote synergism and prevent too many side effects. There is a role of even withholding certain drugs which may have significant side effects.

Palliative care also encompasses psychological support for patient and family. Anxiety and depression are the most common, requiring counselling provided by trained counsellors to both patients and family members. Active listening is the most common tool practiced by trained volunteers; a clinical psychologist should provide the technical expertise where required. Issues of interpersonal family dynamics, family collusion, and bereavement are key areas of support to patients and family provided by the counselling team.

Social support in the form of educational help for children, free medications, and empowerment of women are some very common practices. Spiritual suffering in India is often multicultural and care is usually provided by the team.

Place of care:

Home, is considered the place patient and family would be the most comfortable, while faced with a chronic life-limiting illness, keeping hospital admissions for acute interventions, and hospice care for end of life, if the patient cannot be managed at home. These are recommended palliative care principles; it is incumbent on the palliative care teams to make this happen, as community services are as yet not universally available in our country. There are efforts in many states to make this possible through the respective health services for the state, but there is a long way forward.

End of life care:

End of life care (EOLC) is a part of the continuum of palliative care and as such a very important yet difficult area. Most family members want to ‘try everything’ even though the situation is painfully obvious. For professionals, there is no law in place yet. Recently, the National Accreditation Board for Hospitals (NABH) has published guidelines for EOLC in hospitals. If ‘quality of life’ is paramount; then withholding unnecessary interventions and even withdrawal is necessary and recognized as ethically correct. Numerous discussions throughout the disease trajectory would achieve these aims.

The Supreme Court of India, in 2018, has approved Advance Directives or Living Wills which could limit unnecessary interventions; though the process still has a lot of factors which need to be worked upon.

Ethics in palliative care:

As in any other branch of medicine, the four cardinal principles: patient autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice apply. When the best interest of the patient is paramount, then withholding or withdrawing an unnecessary intervention is considered best ethical practice. The risk-benefit ratio must be calculated at every interaction and communicated with patient or surrogate if the former is not able to take part in decision making.

Good communication at all times is the best way forward; keeping all options available at all times in the discussion. Needless to say, the physician should have all the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitude.

Conclusion:

WHO has recommended that palliative care be integrated into health care in all countries. It is a long way from happening in India. All professionals can practice palliative care principles. Good communication with the patient and family from the first interaction would obviate the need for legal recourse.

Courtesy: Today’s Clinician

Frequently asked questions on PALLIATIVE CARE

Q. Is Palliative Care the same as Hospice Care?

A. Yes, the principles are the same.

Hospice means different things in different countries – it is variously used to refer to a philosophy of care, to the buildings where it is practised, to care offered by unpaid volunteers, or to care in the final days of life. It is better to adopt and use the term palliative care, a term understood by and used by health care professionals

Q. Should a Palliative Care service provide care for patients with chronic diseases?

A. No, although their care is important. Patients with chronic conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, degenerative diseases, diabetes mellitus and similar conditions usually do not have active, progressive, far-advanced disease. Nevertheless, many of the principles of palliative care are appropriate to the management of patients with chronic diseases.

Q. Should a Palliative Care service provide care for patients with incurable diseases?

No, although their care is important.

As with patients with chronic diseases, these patients usually do not have active, progressive, far-advanced disease. Nevertheless, many of the principles of palliative care are appropriate to the management of patients with incurable diseases

Q. Should a Palliative Care service provide care for patients incapacitated by their not-life-threatening disease (eg stroke, post trauma disability)?

No, although their care is important.

Patients incapacitated by psychiatric illness, cerebrovascular accidents, trauma, dementia and the like deserve special care but they usually do not have active, progressive, far-advanced disease. Nevertheless, many of the principles of palliative care are appropriate to the management of patients incapacitated by their disease

Q. Should a Palliative Care service provide care for the elderly?

No, although their care is important.

Many patients needing palliative care are elderly but they need palliative care because of the underlying disease from which they are suffering, not because of their age. Nevertheless, many of the principles of palliative care are appropriate to the management of the elderly /geriatric medicine

Q. Is Palliative Care just Terminal Care / Care of the Dying?

No.

the provision of high quality care during the final days and hours of life is an important part of palliative care palliative care should be initiated when the patient becomes symptomatic of their active, progressive, far-advanced disease and should never be withheld until such time as all treatment alternatives for the underlying disease have been exhausted palliative care may be appropriate long before the terminal phase.

Q. Should Palliative Care stay separate from mainstream medicine?

No.

Palliative care originated because of the belief that terminally ill patients were not receiving optimal care and there was for a long time mutual distrust between the practitioners of palliative care and orthodox medicine modern palliative care should be integrated into mainstream medicine. It provides active and holistic care that is complementary to the active treatment of the underlying disease. It will foster palliative care skills for other health care professionals, particularly better pain and symptom control and appreciation of the psychosocial aspects of care

Q. Is Palliative Care not just ‘old-fashioned’ care?

No.

Palliative care was originally separate from mainstream medicine, and was frequently practised by very caring individuals who knew little about medicine. Modern palliative care is more integrated with other health care systems and calls for highly trained doctors and nurses, competent in a range of medical disciplines including internal medicine, pharmacology, communications skills, oncology and psychotherapy

Q. Is Palliative Care what you do when “nothing more can be done”?

No.

No patient should ever be told “there is nothing more that can be done”—it is never true and may be seen as abandonment of care. It may be permissible to say there is no treatment available to stop the progression of the underlying disease, but it is always possible to provide care and good symptom control.

Q. Does Palliative Care include euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide?

No.

A request for euthanasia or assisted suicide is usually a plea for better care or evidence that more care and support are needed by relatives. Depression and psychosocial problems are frequent in patients making requests and both can respond to appropriate care. Unrelieved or intolerable physical or psychosocial suffering should be infrequent if patients have access to modern inter-professional palliative care. Terminally ill patients suffering intractable symptoms can be treated by sedation; this does not constitute euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide.

Q. Is a Palliative Care service really a pain service and its doctors’ pain specialists?

No.

Most but not all patients needing palliative care have pain of one sort of another but there are usually many other reasons for their distress. Focusing on pain to the exclusion of the others does not help the patient. Palliative medicine doctors have all had advanced training in pain management but not necessarily in invasive measures (though these are less frequently used in modern palliative care.). Their training has embraced all aspects of suffering — physical, psychosocial and spiritual — but their certification is in palliative medicine, not chronic pain management.