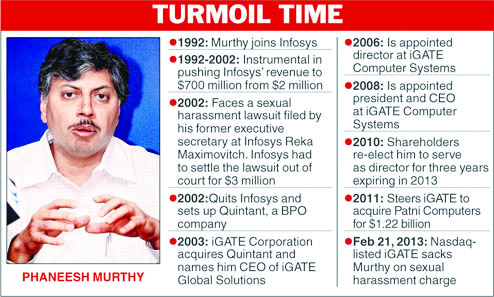

MOLESTATION: Phaneesh Murthy a senior Executive of Infosys based in the United States were sacked on charges of sexual harassment. If the incident had happened in India it would have been buried under the carpet

By Ragini Bhuyan and Piyush Aggarwal

While sexual harassment in politics and sadly even in journalism has attracted a lot of attention, not enough has being done to check the much larger practice of sexual harassment in the corporate world/. From the boss making passes at his secretary to senior managers demanding sexual favors for promotion is very wide spread. Abroad Chief Executives have been forced to resign but in our Bharat Desh (India) the bosses call the shots.

These companies belonging to the BSE 100 universe were mandated to report the number of women employees in their ranks, and the number of sexual harassment charges made by them since 2012-13.

Ever since the sexual harassment charges against the powerful Hollywood film producer, Harvey Weinstein were publicised last month, women from various industries across the world have come out to narrate their own accounts of exploitation, often at the hands of predators in high places.

MOLESTATION

While credible data on the extent of sexual exploitation across all industries is hard to come by, new regulations introduced by the capital markets regulator a few years ago allow us to examine the trends in reported instances of sexual harassment across India’s top 100 companies. These companies belonging to the BSE 100 universe were mandated to report the number of women employees in their ranks, and the number of sexual harassment charges reported by them since 2012-13.

For this analysis, we consider 52 of these firms for which consistent data is available for the past five fiscal years (from fiscal 2013 to fiscal 2017). Some firms have been excluded because of accounting changes, mergers etc. Others have been excluded because they have not clearly mentioned either the number of women employees or the number of sexual harassment charges in one or more years in the time-period under consideration.

The data shows that the number of reported instances of harassment has risen over the years. The ratio of the number of harassment cases to the number of women employees on company payrolls has also moved up.

However, this may not necessarily indicate that harassment per se has increased. As the Weinstein episode reveals, sexual harassment charges tend to be under-reported. This is also true of gender crimes in India in general. Thus, part of the increase in the proportion of sexual harassment cases may simply reflect a ‘reporting effect’ owing to greater awareness of redressal mechanisms.

The number of companies reporting instances of sexual harassment has also been rising over the years, suggesting that companies may gradually be putting in place monitoring and redressal mechanisms. In fiscal 2016, four companies did not report data on sexual harassment. This number has reduced to two in fiscal 2017.

However, the absolute numbers may be slightly misleading because the services sectors also tend to employ more women. When normalized with respect to the number of women employees, it is manufacturing and infrastructure firms that rank higher in terms of reported sexual harassment charges.

SEXUAL HARASSMENT

In general, larger and more valuable firms seem to report such cases more than smaller or less valuable firms, the data suggests. When companies were divided into four groups based on their market capitalisation, the groups with higher market capitalisation tended to have higher numbers of sexual harassment.

But it is worth noting that there are big exceptions to this trend. As the Sensex chart above shows, some of the most valuable blue-chip firms reported zero instances of sexual harassment over the past fiscal year.

The economic costs of sexual harassment are difficult to quantify but they may be quite significant. In a recent study that attempts to quantify the economic consequences of sexual harassment on streets, Girija Borker, an economist at Brown University found that women students of Delhi University were more likely than their male counterparts to choose a college that had a perceived safer travel route, even if that college was of a significantly lower quality. Borker estimates that the willingness to pay for safety meant that women’s post-college salaries were 20% lower than their male colleagues. Her analysis suggests that the fear of harassment may often force women to make relatively poorer economic choices.

SKILLED WOMAN

The trade-off between safety and financial security that women face may also partly explain India’s low female workforce participation rate, Borker argued. This in turn could be hurting India’s productivity and economic growth, as the fear of harassment may be keeping many skilled women away from the workforce. According to World Bank estimates, India’s economic growth can rise by a full percentage point if it even manages to raise its female work participation rate to the level of Bangladesh.

Adequate monitoring and redressal of sexual harassment in firms can play an important role in creating an enabling environment for women. The rising spotlight on sexual harassment across the world will hopefully spur more firms to deal with this issue more seriously.