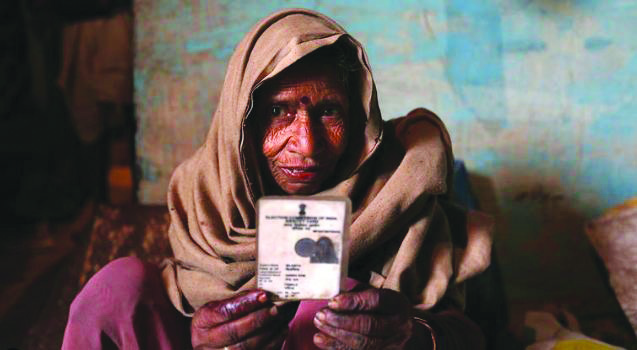

AADHAAR HAI: Bilasia Bai, a resident of Kohani village, has Aadhaar does not have Janam Kundali of either her children or her parents. This will make her liable to victimisation as a refugee from Bangladesh to be sent to externant camp.

By Milind Ghatwai

As a survey of Gangayan, a rural taluka in Madhya Pradesh, where illiteracy is over 90% shows no one has his/her birth certificate. Forget about baap ka naam! Everyone may have an aadhaar card, but they are full of mistakes. Residence will not be able to answer the majority of 21 questions they will be asked under the National Population Register from April Fool’s Day.

Bilasia Bai doesn’t trust her son with her papers. “What if he burns them in a fit of anger,’’ she says, pushing open the tin door to her nephew’s house, barely a few feet from her home, and slowly taking out a large bag from a niche in the wall. It’s a windowless mud house with mud floors, much like the other homes in Kohani village in Shahpura tehsil of Madhya Pradesh’s Dindori village.

VITAL DOCUMENTS

In the deep recess of the yellow bag that’s ridden with holes are her Aadhaar card, a passbook and a Samagra Parivar Card, which assigns a unique eight-digit number to each family that benefits from government schemes. Launched during the Shivraj Singh Chouhan-led BJP regime, beneficiaries use the card for all social security schemes, including to get pension and ration.

Her son, a daily wager, is alcoholic, she says, and often beats her up. “My daughter goes out to work too. I go home only when she is around,” says Bilasia, who is in her sixties.

A few years ago, Bilasia’s husband walked out on her. “He left me for another woman. I don’t think about him anymore. I have no hope that he will return or that my son will behave better. These papers are all I have. Where will I go if they are destroyed,” she says. The family owns no land.

As the debate over the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and a nationwide National Register of Citizens (NRC) roils the country, with fears that people will be asked to prove their citizenship, Madhya Pradesh’s Dindori district, among the poorest in the country, has been largely untouched. The administration says there have been two rallies so far — one pro-CAA and the other against — and both passed off peacefully. But in a district where 64.9 per cent — the highest in the country — reported “none of the assets specified” to a question in the last Census on whether they had assets such as television, personal vehicles or phones, the “kagaz”, or documents that establish identity, have always been a prized possession, wrapped in polythene or cloth bags, or tucked away in iron petis. They have determined who gets to go to school, who doesn’t; who gets a scholarship, who doesn’t; who comes back from the ration shop with the 5-kg rice or wheat each person is entitled to, who comes back empty-handed.

MISTAKES IN AaDHAAR

A few feet from Bilasia’s nephew’s house, seated in front of another mud house is Hanumat Vishwakarma, a 35-year-old father of three. He disappears into the darkness of his house and comes back with his “kagaz”. But there are problems, he says. When he got his Aadhaar done the first time, it carried only his first name. The second time, it came with a surname, but a wrong one – “Dhurve”, which would have made the landless Dalit a tribal. “I will have to go to the local Aadhaar centre again… I don’t like going there. All these places are only for the rich, those with money to spare,” he says sullenly.

His eldest daughter, 13 years old and a Class 6 student, is speech impaired. “Her teacher told me to get a disability certificate… that I will get money under some scheme,” he says. Someone in the village told him the certificate can made at Dindori, the district headquarters, more than 60 km away. So the daily-wage labourer skipped a day’s work to make the trip — “it cost me more than 100”. But at Dindori, they told him the certificate can be made at Shahpura, barely 15 km from his home. “I will have to go another day now,” he says. Like Bilasia, Vishwakarma hasn’t heard about CAA or NRC. Over the years, while mobile phones and a shiny road network have made their way to most remote villages of Dindori, with no industries to speak of, most people go as far as Mumbai, Ahmedabad, Bhopal and Jaipur in search of work. Jobs under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme are erratic, “only when panchayats come up with some work”. At the anganwadi in Kohani village, the children have left for the day and anganwadi worker Shashi Dhurve is preparing to leave. Dhurve, who has been working for close to two decades, says she is preparing to apply for a PAN card. “Since I have a job, someone told me I will need a PAN card in case I decide to apply for a loan in the future,” says Dhurve, who earns10,000 a month.

She admits she has no idea about NRC or CAA but knows that “people without documents face a lot of problems”.

Around 3 km from the anganwadi, at Dhurve’s house, her husband Haridas, a farmer, says he does not own a mobile phone but has heard about CAA and NRC and knows documents are “crucial these days”. Taking out a plastic bag from the steel almirah, Haridas says, “If we are ever asked to prove our citizenship, we have Aadhaar. It’s the most important document in our lives.’’

SPELLING IN CORRECTION

“Before CAA and NRC, our only grouse was that our Aadhaar cards never got our spellings right because the people at the centre feeding all that data into computers can’t differentiate between common Muslim names,” says Mohammed Qasim, a 40-year-old trader of wheat and rice at Vikrampur village, off the main road leading to Dindori. “Now we have bigger worries,” he says.

Unlike the other communities of Dindori, its Muslims, who make up less than 1 per cent of the population and whose members are scattered in villages across the district, mostly small-time traders and small landowning farmers, are aware of CAA and the NRC, and admit to being fearful and confused.

HINDU MUSLIM RIFT

“They (the government) are creating a rift between Hindus and Muslims. They want to establish their badshahat (supremacy),’’ he says. Among the wealthier Muslims in the village, his family has “all the documents”, he says, from Aadhaar to land records. The family owns a TV, fridge, sofa, and a motorcycle, among other “assets”.

“They came for the Muslims first, then they will come for tribals and later Dalits,’’ says Anis Khan, 44, sitting in his house in Shahpura village. Anis admits he has picked that line from “informal conversations”, but says it could well come true.

The 44 year-old says farmers will stop selling their produce to teach those backing the legislation a lesson. His father Mohammad Hamid Khan, who has joined the conversation, listens impassively, before he says he fears a backlash.

“Nahin, nahin (no, no),” the son protests. “Hindus hamare support mein hai. Keval BJP aur RSS walon ko chhodke (The Hindus are with us, except for those with the BJP and RSS),” he says.

It’s 11 am and the Aadhaar Panjian Kendra in the district headquarters has come to life. Young couples, toddlers swathed in blankets and sweaters, school girls and the elderly stand patiently in queues, awaiting their turn at the two-room centre, not far from the collectorate.

Dasru Lal Yadav and his wife have travelled 30 km from their Darri Mohgaon Mal village to stand in the queue. A fortnight ago, Dasru had applied for updating his Aadhaar card. In his 50s, Dasru owns only one acre, which makes him eligible under the PM-Kisan Yojana Samman Nidhi Yojana. Though the Central scheme, which promises `6,000 a year as income to small and marginal farmers, was launched a few months ago, Dasru has not got any money so far due to spelling errors in his Aadhaar card, which don’t match the details in his bank passbook. “Modi wale paise nahi mile, baki sabko mil gaye (We haven’t got money under the Modi scheme; everyone else has got),’’ says his wife Lalti. Till his Aadhaar card is updated, Dasru will have to continue looking for work in places as far as Bhopal.

After waiting for close to an hour, when his turn comes, the official at the centre looks up his details and says dryly, “Process mein hai. Char-paanch din aur lagenge (The application is being processed. It will take 4-5 days).’’ Yadav quietly nods and turns around. The couple will now make the trip back home, only to come back and stand in the queue some days later.

REPEATED TRIPS

At the centre, there are no less than 30 people in the queues — some to make new Aadhaar cards, which is done free of cost; others to update or correct mistakes in the old ones, for a fee of `50. It takes up to three months for a new Aadhaar to be delivered at home. A wall at the centre lists 35 documents — passport, driving licence, among others — that applicants have to furnish to carry out changes in name, address, date of birth and other details.

But hardly anyone stops to look at the wall; instead queuing up for hours just to get to the data-entry operator or the assistant at the centre who then hollers out instructions.

According to District Collector Bakki Karthikeyan, Aadhaar penetration in Dindori is complete. “Almost every body is documented because of Aadhaar, Samagra Parivar Card, job cards under NREGA. People don’t have to come to Dindori because all paper work is done either at the block headquarters or at gram panchayat level,” he says.

Metres away, at the Dindori District Hospital, a 100-bed facility whose Out Patient Department sees about 200-250 patients a day, Chief Medical Health Officer Dr R K Mehra says about 900 patients have benefited so far from the Centre’s Ayushman Bharat scheme since its launch in 2018. “But the biggest problem for the beneficiaries of the Ayushman scheme is the mismatch between the 2011 Socio Economic Caste Census, which is the basis for Ayushman Bharat, and the details on their Aadhaar cards. If these spelling and factual errors in the documents are not enough, there are issues of Internet connectivity. Since much of the authentication happens online, erratic online connectivity is a problem. We ask for documents only from patients applying under the Ayushman scheme,” he says.

SHORTAGE OF DOCS

The district hospital, which has seven community health centres (CHCs), 22 primary health centres (PHCs) and 219 sub-centres under it, does not carry out Caesarean operations because the only anaesthetist the hospital had was transferred six months ago. “Barring the 17 MBBS doctors attached to the government hospital, there are just four MBBS doctors in the district who can practise privately. Three of them are into politics and one is a retired government doctor. Women have to go to Jabalpur, 150 km away, for C-sections,” says Dr Mehra.

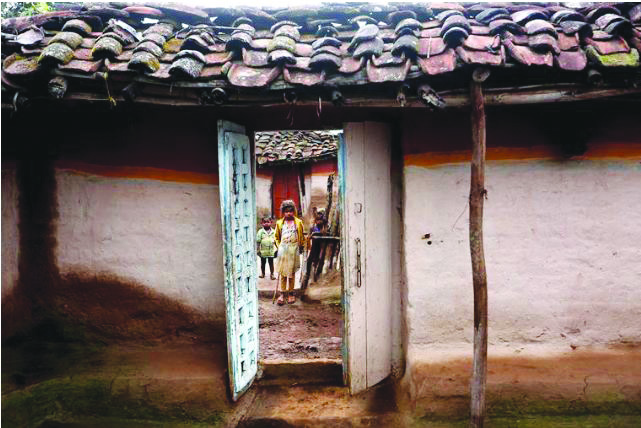

Less than 25 km from the district headquarters is Goyara, a village with a mixed population of Baigas and others. Along with the Gonds and other tribals, the Baigas, a primitive tribe in Madhya Pradesh, make up 64.7 per cent of the district’s population.

The only motorable road to Goyara, a hamlet of mostly mud homes, has been rendered unusable after sudden showers lashed the region recently. It’s here, at one end of the village, that Bisram Bhoka, a 47-year-old Baiga tribal, lives with his wife. All his three daughters are married and live separately.

Bhoka’s documents spell his first name in different ways — “Bisram”, “Visram”, “Bisaram”… Carefully wrapping his documents back in a piece of cloth and placing it on a makeshift loft, Bhoka says he is worried about something else. “I used to get 35 kg rice earlier, but now I only get 15 kg a month. I have asked a few people. Some say I must go to Dindori again. All that way….”