Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

BREAST,VAGINA IS BARRED!

Feb 01- Feb 07 2020, POETRY January 31, 2020CENSORED: The Goa chapter of Sahitya Akademi winning Goan poet has been questioned for using words like breast and vagina to describe body parts of a women.

By Smita Nair

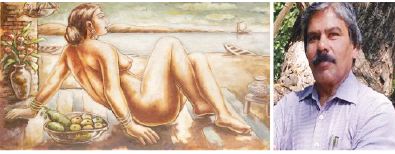

Konkani poet Neelba Khandekar who has won the Sahitya Aademi award is being harassed for using the Konkani words for breast and vagina in his poems. How else do you describe these body parts he asks.

Konkani poet Neelba Khandekar on the controversy over his Sahitya Akademi-winning volume of poetry

Konkani poet Neelba Khandekar, 60, will be in New Delhi on February 25 to receive the 2019 Sahitya Akademi Award for his collection, The Words (2017). Khandekar, has been battling Goa Konkani Akademi, a state government body, which has rejected the purchase and circulation of the book over “objectionable and obscene content”. Reputed in Goa’s Konkani language circles as a poet who “reflects the society”, one of his poem, titled Gangrape, in the 43-poem anthology has been singled out for using words like yoni and thann (vagina and breasts in Konkani).

It’s unfortunate. There can be nothing more tragic than when a poet has to explain his poetry. It’s a self-published book, and, like the other 63 authors and poets shortlisted this year, I, too, sent the book to the Akademi under the Publishers Assistance Scheme. The scheme allows the Akademi to purchase and circulate published works. Mine was the only book that was rejected. For the last one year, it’s been rather disturbing and tiring to travel 35 km to file RTIs and attend hearings. They refuse to give an official or formal explanation and I am going every few days to seek answers. The two words – I have been informed unofficially – that caught their attention and were seen as “objectionable and obscene” are the anatomical words for ‘vagina’ and ‘breasts’. Going by their own argument, I would counter, these are how one describes the parts of the body and I haven’t used the slang or the derogatory term.

How do you see these RTIs and engagements ending?

I am going to fight this. It’s not about money or purchase order for me. I want them to take back the diktat that the words are ‘obscene or objectionable’ or that the poetry on gangrape is offensive or ‘dangerous to the audience’. The prologue of my book reads: ‘Words are the beginning of my existence, they are the end of my desolation’. For me, this is the fight for words. Last time, they had banned a book, Sudhirsukt (2013), by the late Vishnu Surya Wagh, who was my neighbour, as it criticised casteism. When I went to the Akademi, the first response they gave for the refusal was by citing the use of these two words, as an example. They said they didn’t want any more ‘controversy like Wagh’.

What influenced the poem, Gangrape?

Poetry, for me, is a journey, a learning of the surrounding and an archive of social reactions. My day begins with reading the newspaper. I am unable to comprehend anything if I have not collected the day’s news. I was disturbed for a long while over the episodes of gangrape: earlier, the 2006 Khairlanji massacre shook me, then the story of Nirbhaya (the 2012 Delhi gangrape incident) made us helpless, and, finally, the 2017 Unnao case angered me. In most cases, we have shown we are the worst species. We abuse and murder our women. No animal is so heinous to abuse and kill the female gender. While, as a society, we should have nursed the victim’s wounds, given her a shoulder, helped her heal, the advocates and the machinery stood by the accused. They even questioned the victim. My words in Gangrape were my reaction to the social injustice around us. I will never speak against a woman, and will never write anything against her. My poem was my expression of the ghastly crime committed on her, again and again. I spoke on behalf of the woman.

How do you sum up your journey so far?

In school, when my classmates would run to buy toffee and popsicles, I would save it to borrow books from the local library. Those days, the adventure and the unpredictable endings in detective novels were too tempting. Regional authors, like SM Kashikar, Baburao Arnalkar and Gurunath Naik, kept me engrossed. Later, I started reading poetry, though it always bothered me that while my mother tongue was Konkani, Marathi was the compulsory subject. I saw the potential of style stronger in poetry. Unlike novels, which are vast but flat in form, poetry was challenging, and compelled one to think through its hard-hitting grammar. This is my personal opinion, though I continue to enjoy reading prose. It was when I joined college that a thought struck me – why am I not expressing myself in my own language? Poetry became a chosen outlet then.

How do you write?

My day job, till I retired recently, was clerical, and hours would be spent doing purchase accounting and mechanically counting money at the Navy’s administrative office in Vasco. I used to scrawl a few lines on waste paper. I would always find them when I travelled back home in the bus, when the conductor asked for change. Again, I would correct it and pocket the paper. I would keep writing lines, adding them, with the words working its magic in my head for hours. In the evenings, in the middle of night, I would keep writing. I like to work the turn of words, the meanings it shapes. I only write when I am convinced, as most of my poetry first happens inside me. Over the years, I have tried to highlight the issue of caste, social oppression and other human injustice. I have tried to bring Karl Marx and Lenin closer to my regional reader, and even Bapu, who is relevant to our past, present and future. He acted his words, and just for that, he keeps getting repeated in my work. My collection bears his influence.

Where does poetry stand today?

Today, political power is becoming prominent, and poetry has been sidelined. Look at the number of poets in the country. Not too many. They are the same 40 or 45 odd poets you have been hearing about for years. We return home to WhatsApp, and the same serials where daughters-in-law and mothers-in-law have been fighting for years on an imaginary planet. Where are the real issues on television? I am pained by the events that happen around us – the atrocities of caste, identity, gender and creed. We are humans …and we should be allowed to die like humans. People don’t even know what levels of atrocities are happening as they are in these parallel worlds. They are so lost in the world of social media that they have no time for reality; it is the poet’s duty today to take a pause and show them the mirror. You find that ignored reality only in the words of a poet today.

Is anyone afraid of a poet?

There is a reason why poets are feared. Hurdles are placed, language is questioned, freedom of speech is impinged upon. Poets are like masons, they build society. Poets may not have the cure or medicine for the social malaise. But their words, written on blank papers, are the beginning of change. Look at all the atrocities around you: memory holds the crime or the crime scene only for a limited passage of time. It’s a poet’s words that make one probe, question one’s reactions. Besides, a poem is always explosive; it says much more in fewer words. It is also a live piece of literature. It blends to the meaning around us.

Poetry is also an exhibition of our diversity, a diversity of our views, our thoughts, all of us. Every experience has its language – victory, sadness, satire… let’s say all these are lived and each has its own experience and expression. Poetry, like any form of literature, walks alongside; it’s a mirror to society. So, if they have issues with the poetry or usage of words, they should take measures to stop or punish the crime. There is no point punishing the poet.