Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

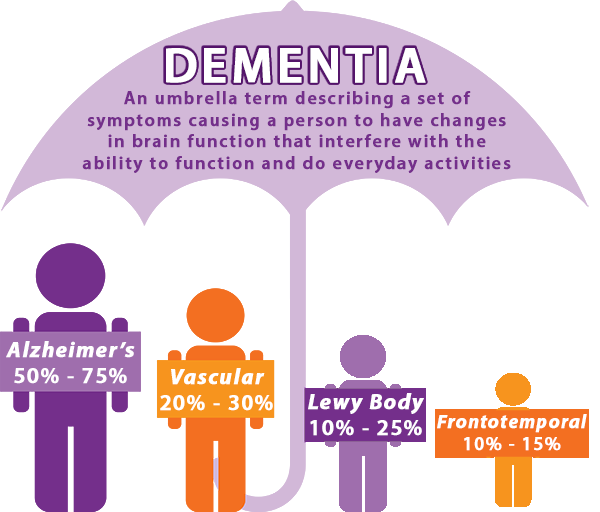

DEMENTIA CAN BE PREVENTED — Lancet Study 2020

Aug 29- Sep 04, 2020, MIND & BODY, HEART & SOUL August 28, 2020When did you last think about dementia and how you can pre-empt it? Here are a few clues…

By Nicholas Parry

A RECENT Lancet study has suggested that through a number of changes to both government policy and individual behaviour, approximately 40% of dementia cases can be prevented. In the process of building a dementia-friendly community medical students in India show their support to dementia prevention and care.

“Our report shows that it is within the power of policy-makers and individuals to prevent and delay a significant proportion of dementia, with opportunities to make an impact at each stage of a person’s life,” says lead author Professor Gill Livingston of University College London in the United Kingdom.

“Interventions are likely to have the biggest impact on those who are disproportionately affected by dementia risk factors, like those in low- and middle-income countries and vulnerable populations, including Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities.” Prof Livingston elaborated that “as societies, we need to think beyond promoting good health to prevent dementia, and begin tackling inequalities to improve the circumstances in which people live their lives. We can reduce risks by creating active and healthy environments for communities, where physical activity is the norm, better diet is accessible for all, and exposure to excessive alcohol is minimized.”

The authors call for nine ambitious recommendations to be undertaken by policymakers and by individuals. These suggestions are as follows, as directly quoted from the Lancet paper

• Aim to maintain systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or less in midlife from around age 40 years

• Encourage use of hearing aids for hearing loss and reduce hearing loss by protecting ears from high noise levels

• Reduce exposure to air pollution and second-hand tobacco smoke

• Prevent head injury (particularly by targeting high risk occupations and transport)

• Prevent alcohol misuse and limit drinking to less than 21 units per week

• Stop smoking uptake and support individuals to stop smoking (which the authors stress is beneficial at any age)

• Provide all children with primary and secondary education

• Lead an active life into mid, and possibly later life

• Reduce obesity and diabetes

Of India’s elderly population, Health Issues India previously reported a phenomenal rate of growth among this subsection of India’s citizens. “In just a decade, India’s elderly population increased from 70 million to 104 million.This change occurred across the 2001-11 period, with the elderly population reaching ever greater numbers since then…as of 2019, those over the age of 60 account for 8.6 percent of the population of India. With a trend towards lower population growth and greater life expectancy, this age group will soon begin to form a larger bulk of India’s population.”

Estimates have placed the number of patients with dementia (of which Alzheimer’s disease is among the more common forms of the condition) in India at around four million. Worldwide, numbers of dementia cases are estimated to hit 131.5 million by 2050. Such increases in dementia rates are being witnessed the world over. Initially, Alzheimer’s and dementia rates were seen to surge in Western nations, while being all but unheard of until recent decades in low- and middle-income countries. This has changed as life expectancies have improved sharply in recent years. As previously seen in Western nations, as life expectancy rose in countries such as India, dementia rates surged.

There are other factors at play, such as the higher prevalence of some of the risk factors of dementia noted by the study. “In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the higher prevalence of dementia risk factors means an even greater proportion of dementia is potentially preventable than in “higher-income countries,” said the report’s co-author, Professor Adesola Ogunniyi of the University of Ibadan in Nigeria. “In this context, national policies addressing dementia risk factors, like primary and secondary education for all and stopping smoking policies, might have the potential for large reductions in dementia and should be prioritised. We also need more dementia research coming from low- and middle-income countries, so we can better understand the risks particular to these settings.”

In many cases– India included– healthcare infrastructure simply does not exist to cope with a rapidly rising tide of those who are affected by dementia. As populations age across the globe, reaching ever higher life expectancies as other disease areas are addressed, dementia is set to become commonplace. Without the infrastructure to deal with these dementia cases, health systems in many nations could be overwhelmed.

The final section of the report stresses this fact. The authors advocate for holistic and individualized evidence-based care that addresses physical and mental health, social care, and support that can accommodate complex needs. With global dementia figures predicted to rise from 50 million to 152 million by 2050 — with LMICs predicted to bear the majority of cases– significant changes are required if India, and indeed the world’s health systems, are to cope with the burden.