Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

FALLING FOR KOHLRABI!

Life & Living, Nov 28- Dec 04, 2020 November 27, 2020The elegant Kohlrabi also known as knol khol, naab, koo bideh, navil kosu… related to cabbage family and much loved in Kashmir Valley! Comes in pale green and royal purple. Botanical name: Brassica oleracea

By Tara Narayan

FUNNY, or not funny. How we sit up and take notice of a vegetable we have seen before but ignored and or wondered about but nothing to get familiar with for years on end! I’m so angry because I’ve never bought the elegant looking long-stemmed leafy kohlrabi before. It took my friend Nandita Haksar (a most fastidious foodie who was waxing lyrical about vegetarian Kashmiri food one day) who fired my interest the kohlrabi. Some say it is weird vegetable but I say it is a most gracefully long vegetable with pale green watery white tones. Kohlrabi come from the German word kohl (“kohl” for cabbage and “rabi” for turnip, they thought kohlrabi was a veggie marriage); but we in India better know is as knol khol (wrongly khol khol) or ganth gobhi, “navalkol” in Maharashtra, “noolkol” in Telugu in Andhra Pradesh, etc.

Anyway, suddenly for all of this month I’ve been looking keenly at this swathy lake-green leaved piles of kohlrabi in the market, totally seduced by how the word flows so smoothly off my lips! And ever since I’ve been so fida over kohlrabi…then I started buying it without knowing how I should best eat it despite Nandita’s instructions. An adventurous foodie you cannot do better than read Nandia Haksar’s political cookbook “The Flavors of Nationalism, Recipes for Love, Hate and Friendship” (published by Speaking Tiger, paperbook, 350). A personal memoir, as she calls it, she weaves an engaging political upbringing with a few special Kashmiri Pandit recipes thrown in like a meaty Khumani…but more about that later. TO stay with this lovely kohlrabi you may see it abundantly these days at the early morning gauti veggies and Goan specials pavement market outside Panaji municipal market. It’s become my favorite outing to begin the day these winter months -- although it’s still a hot November this year. One sees the pale green (drying leaves turning ashy blue) kohlrabi but occasionally the eyes light up seeing the pure purple kohlrabi which too are exquisitely eye catching. Kohlrabi can be hefty and coarse leafed with heavy bulbs or globes, but do look for smaller, tender bulb kohlrabi which have lots of fresh baby leaves….truly, these long-stemmed kohlrabi are beauties. Pricewise they’re pretty expensive. All vendors quoted20 per kohlrabi or “take three for panas (50)” and I fussed, most expensive vegetable in town, how can it be so expensive! Give me just one for10 because I only want to find out what this vegetable is all about, but it was nothing doing and finally I selected one kohlrabi from the pile which looked like it had greener baby green leaves and a small, tight bulb. La, la, la…so pretty. I haven’t seen a prettier vegetable than kohlrabi. Anyway, this kohlrabi is singing a high note of joy in my life these days, can’t take my eyes of it.

Kohlrabi is not a root vegetable and do not belong to the turnip family okay. Botanically kohlrabi belongs to the Brassica genus of plants and is related to cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, kale, Brussels sprouts, Savoy cabbage, gai lan, etc, I dare say kohlrabi taste comes closest to broccoli stems, slightly sweeter maybe.

IN KASHMIR I’m told the Kashmiri Pandit community love kohlrabi as one of their khaas vegetables; upon chewing some of Nandita’s brains she recited a garbled recipe of how her bua cooked kohlrabi and I said it’s too complicated, forget it; only her bua gone with the wind knows how to cook it in true blue Kashmiri Pandit style with lots of mustard oil and wadi or bari! From the gist of it one chops the “saag” (kohlrabi greens with bulb chopped or cubed after top leathery skin is removed and all fibers left), and then temper in mustard oil, cumin seeds, two dry red chili, pinch hing…later you may add dried spiced-up lentil nuggets or cakes called “wadi” in them, salt and jaggery as per taste.

Serve atop rice of course. Kashmiris are pukka meat and rice eaters. Well, one will find scores of kohlrabi recipes at Facebook cookery sites if you do some homework.

What I did was try to make a butter-enshrined soup but I didn’t realize kohlrabi can be so fibrous and therefore my soup too turned out over fibrous and chewy. I had to spit out the chewed up fiber globs! But it was a lovely creamy green soup because to retain the coloring I’d added a pinch of sweet soda to it at the beginning…soup stock was so celestially tasting and to live for, of course I had to sieve out much of the fibrous greens before re-warming, salting, peppering and sipping it feeling nice and warm and determined to perfect my kohlrabi soup next time around. Will make it again but this time I will use only the tender leaves and maybe puree the bulb after skinning it more thickly.

Hey, once the exquisite creamy waxy skin is off one arrives at a crunchy watery loveliness within with a faint aroma of cabbage…one may slice the skinned bulb thinly and add it to a coleslaw salad with a lemony dressing. I imagine that would be utterly delicious. Kohlrabi is a very vitamin C, antioxidant rich veggie and you must know how vitamin C speeds up virtually all wound healing. The veggie plays a role in collagen synthesis, iron absorption, boosts immune health.

Plus, kohlrabi and family of brassica veggies offer vitamin B6, potassium, support red cell production…their electrolytes are important for heart health and fluid balance. A single cup of 135g of kohlrabi provides approximately 17% of daily fiber needed. It is dietary fiber which helps supports gut health and blood control (all that fiber I was complaining about earlier but too much can be too much and one may not over do it on the fiber front important though it is).

More notes: The kohlrabi beauties are related to wild cabbage. It’s an ancient vegetable dating back to it origins to the first century AD – like I said kohlrabi gets its name from the German word “kohl” for cabbage …people thought it was a cross of a veggie between cabbage and turnip earlier on but this is not true. People across Germany, Central Europe and parts of India, China and South East Asia love kohlrabi and use the veggie greens and bulb in various ways to intrigue and captivate the senses. Both pale ivory green and purple more or less offer same flavor.

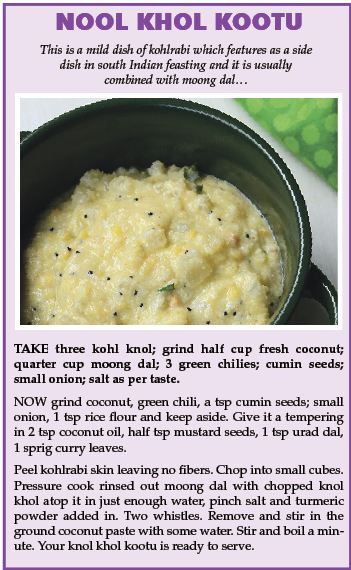

THIS is to say you may slice kohlrabi flesh finely thin and eat it raw in salads or stir-fries or do mashed kohlrabi instead of mashed potatoes. Down south India I’m told they do a knol khol kootu (“nool khol koot”). Can also do simply delicious crunchy water pickles with kohlrabi thick chunks or slices and this I’m interested in now…let me see, veggie water pickles are all the rage because of the probiotic virtues credited to them in such item numbers as the German sauerkraut or Korean kimchi or Indian lemon pickle or I’d say even Goan mango chepnim.

One may just about water pickle any vegetable to enrich it with great flavors. Go look for kohlrabi this week, my dears and share some recipes with me here if you wish!

Excerpted from ‘The Flavors of Nationalism’ by Nandita Haksar…

AMMA’S repertoire was wide-ranging, from basic Kashmiri food to absolutely delicious ravioli and spaghetti bolognaise, which simply melted in the mouth. Many times I find myself longing for her chicken casserole and tamatar-aloo sabzi. She had trained our cooks , even Joseph, in Kashmiri cooking. But within the family Amma did not enjoy the same formidable reputation as Bua or Papa. I resented this deeply.

I am sure Amma did too. She did not want her identity to be that of a mere housewife. She used to grumble because every single day she would ask: `What would you like for lunch?’ or `What shall we have for dinner?’ And invariably we, Papa and I, would answer: `You decide.’ I did not understand why she so much resented deciding the menu every day. Now I do.

As a child, I knew Amma harbored deep resentment against a life where she could not realize her full potential. She did not understand institutionalized patriarchy the way my generation of feminists did. If Amma had read Betty Friedman’s Feminist Mystique (1963) she would have identified with its central idea that women need to find personal fulfillment outside their traditional roles. But she would have said Betty Friedman did not deal with the wider forms of social inequality, oppression because of class, colonialism or imperialism.

For Amma, the difference between men and women was a kind of discrimination and inequality; she felt strongly about women’s rights but was not familiar with concepts like gender and patriarchy. She would have dismissed Betty Friedan because she was predominantly dealing with the problems of white middle-class women in the United States. Amma, and women of her generation, could not de-link the oppression of women from the wider struggle for the liberation of human beings from class exploitation and imperialism. So Amma continued to play her role as mother and wife, but would often complain: `I am a doormat on which everyone wipes their emotional dirt off.’

In a perverse way, it was a protest of sorts that she never really let people know she could or even knit. And this attitude rubbed off on me; I refused to learn any of the skills women were supposed to have. And even when I could cook I would not tell anyone.

Many, many years later, I teased Amma that after she died I would not remember `Maa ke haath ka khana’, food cooked by my mother’s hands. And she retorted: `So that’s the kind of feminist you are. You want to remember your mother only by the kind of food she cooked.’