Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

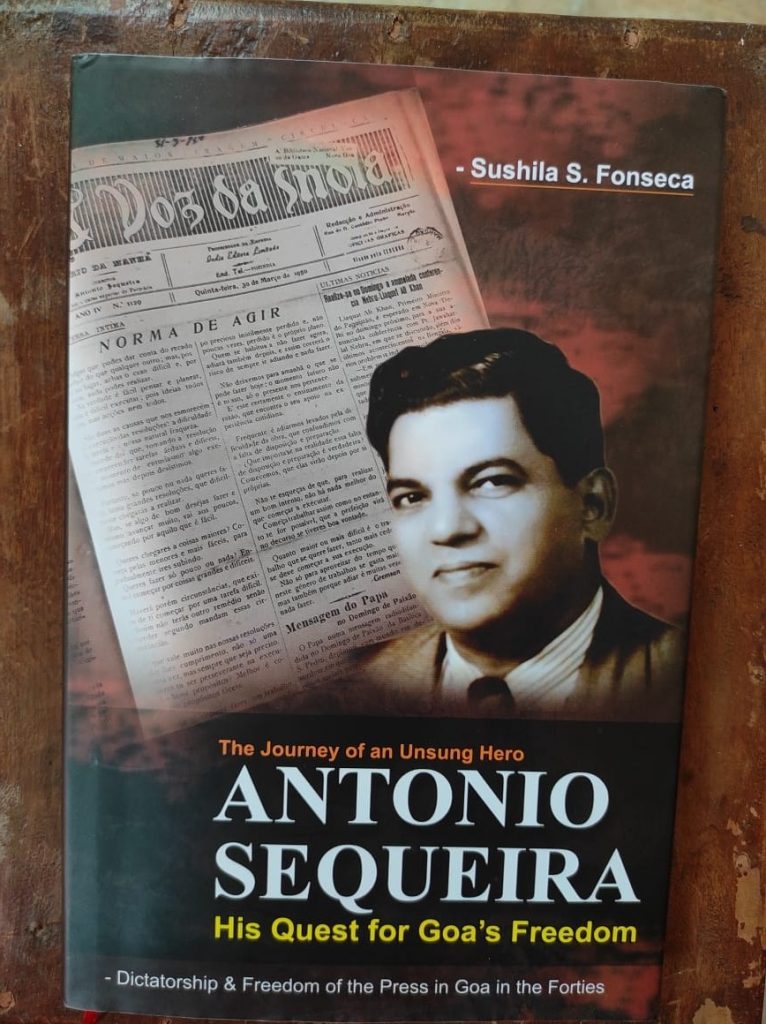

REMEMBER UNSUNG HERO ANTONIO SEQUEIRA!

May 01- May 07, 2021, Potpouri April 29, 2021Author Dr Sushila Sequeira Fonseca is the daughter of Antonio and Ermelinda Sequeira. She is a consultant pathologist and also writes as and when the muse strikes. She is the author of several fiction and non-fiction works and is a Goa State Cultural Award Winner (Literature in English 2018-2019)

‘The Journey of an Unsung Hero Antonia Sequeira, His Quest for Goa’s Freedom’ by Sushila S Fonseca (hardcover, 2021, Rs599)

WITH the menace of a exclusively Indian strain of corona virus (NoB1617, whatever it means) in the air I’ve been forced to more or less at home, something very difficult for me to do for I feel mostly out of doors! But when at home one is besotted with Facebook posts, but this time for a change I’ve been engaged with Dr Sushila Fonseca’s new book The Journey of an Unsung Hero Antonia Sequeira, His Quest for Goa’s Freedom’ (hardcover, 2021). Dr Sushila has one of the keenest perception of things, apart from being a much trusted pathologist in town, her books are simply elegant affairs and offer insight into some rarely covered aspects of Goa’s Portuguese-time colonial history. The good pathologist is a keen observer of the times she’s been privileged to live through and uses her time fruitfully to show us the other side of the coin or so speak. In her new book she’s personally involved forAntonio Sequeira’ is about her own father’s life and times and one realizes how rich Goa’s history is vis-à-vis very many stories of courage and valor during colonially oppressive times! Not only the Goan Hindu side but also on the Goan Catholic side. And history chaser Dr Sushila Fonseca has been a witness to some of it in her own family vis-à-vis the life and times her parents Antonio and Ermelinda Sequeira lived, and as if with latterday hindsight she has done her homework and come up with her latest book titled ‘The Journey of an Unsung Hero Antonio Sequeira, His Quest for Goa’s Freedom.’

Amongst other tidbits the book offers some amusing and interesting perceptions and perspective into the Liberation years and how even freedom of the media suffered, had to be compromised with given the prevailing dictatorship of the Salazarist regime in Goa. Read the book also to understand a more or less similar situation today with a difference (when media is under attack for the stand it takes on human liberties).

In recounting her parents’ life and times during Portuguese rule over Goa the author tells us how her father was affected by media censorship in the mid-1940s, when her father Antonio Sequeira was director and editor of the Portuguese daily A Voz da India’ during the few crucial years it contributed to voice of the freedom movement in Goa. And mind you Antonia Sequeira was a respected lawyer, a pharmacist, keenly conscious of a colonial ruler’s misdeeds and cruelties as it impacted the people of Goa converted and not converted. Regardless of religious differences all were Goans in mind and heart rooted in the red soil of Goa, no matter they may have lived in Portugal or the other Portuguese colonies of those years. So we have Antonio Sequeira in the forefront of the movement for the liberation of Goa from colonial rule and the book throws up fascinating facets and sentiments – of a couple undoubtedly owing allegiance both to their Portuguese as well as native Goan identity. If you want to see the other side of the picture of Goa’s Liberation here it is very simply yet evocatively recounted inAntonio Sequiera’—a man conscious of the yoke of colonial rule and committed to freedom.

His liberating `A Voz Da India’ was banned, a warrant issued for his arrest and he was compelled to run away from Goa to escape arrest. It was a Portuguese newspaper which dared to take the side of other more familiar names calling for liberation from Portugal, like Dr TB da Cunha. But the author rues that her although her father’s contribution to the cause of Goa’s Liberation was critical, later on it remained unsung and forgotten! In a sensed the book could be a daugher’s effort to fill in the blanks in memory of her father and parents life and times.

You’ll have to read the book for the nitty gritty of her parents overt and covert views about the shortcomings of Goa’s Portuguese rulers. A bit of background: “Antonia was born on 20th November, 1911, in Loutolim and he grew up in Raia – both these villages were prominent ones in the south of Goa or Portuguese India as it was called. Antonio’s was a Goan Brahmin Family, of strong Christian faith. Many members of the family attributed his birth to the prayers and promises made to their favorite saints for their intercession with the Almighty Creator to bestow Aleixo and Quiteria with a boy child. Therefore, when Antonio was christened, not only was he named after his grand-father as was customary but the names, of the many saints prayed to, were also added on. Thus, he finally had multiple names. There were Eusebio Antonio Roque Sebastiao Salvador Francisco Xavier da Piedade Sequeira but he became known to everyone just as Antonio Sequeira.’ He was born to a well to do bhatkar or landlord family of Goa which moved amongst the crème de la crème of society of the day.

A good family, education, profession, he did a course in pharmacy, later on he also obtained a license to practice law in Quepem. Her father, says the author was a multi-dimensioned entrepreneur and also a child of nature, “had a weakness for white butterflies. To him they were a good omen: he reckoned that they brought him good luck! For him, the appearance of black butterflies was a warning of impending danger and one had to be very careful! Be it as it may, the fact is that on more than one occasion, he did see white butterflies when taking an important decision, which turned out well for him.”

A life well lived in palatial homes, a loving wife with golden singing voice, a charmed life one would say when the children came along…and yet the author writes about the struggles of the mind as the chapters of liberation history turned. Some familiar history, some unfamiliar insight into how the Governor-General of Goa in charge of governance depended mainly on orders from Portugal’s Minister for Colonies…the years of Salazar’s dictatorship regime became a period of discontent for all Goans and arose the reasons for revolution. Goa’s economy was in the doldrums and a black market thrived.

The writing is comprehensive enough to serve as a refresher course to young Goans today who may be taking their freedom too much for granted today! Dr Susheela Fonseca has a gamut of selected quotes from the many players of the times which led to Goa’s Liberation and in all this her parents’ lives were intertwined. Especially her father’s life who was passionate about Avoz da India (The Voice of India) which was a daily newspaper published in Portuguese in Goa, which was also known then as Portuguese India. The first edition of this newspaper, was published in May 1946 and retired judge and advocate, Vicente Joao de Figueiredo was the first owner and publisher…A Voz da India consisted of four pages yet it made an impact on its readers during the pre-Liberation years.

Media students may do well to read up this book! Lots of yesteryear photographs with Ermelinda getting involved in Gandhiji’s causes, the early 50s were difficult times and the couple had to emigrate for greener pastures (Ermelinda pragmatically sold off her gold jewelry to create funds for a new life abroad). The family lived in Mombasa, Kenya, from 1952 to 1970, so we get some insight into Goan life in Africa. I appreciate the remarkable selection of quotes the author has used before each chapter…you want to understand Goa more, go read the book. A better understanding of history cannot but better heal the wounds of the soul, I would say Sushila S Fonseca’s new book unerringly helps to do just that.

ON that note it’s avjo, poiteverem, selamat datang, au revoir, arrivedecci and vachun yetta here for now.

Excerpted from ‘The Journey of an Unsung Hero: Antonio Sequeira’

by Sushila S Fonseca…..