DIGITAL: Traditional media like print and television, which were the main campaign platforms of political parties, have given way to social media tools such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Youtube, etc.

By Anuradha Rao

In line with the global trend, social media has been increasingly used by Indian politicians for routine political communication to directly connect with their supporters. However, unethical practices online by political actors have led to a spike in violence and affected decision-making on the national security front.

Social media played a prominent role during the 2019 Indian general elections as political parties, politicians, and supporters (real or otherwise) used it extensively for political campaigning and communication. Following the global trend, social media has been increasingly used by Indian political actors for routine political communication between elections to provide unmediated and direct communication to connect leaders and citizenry, and to re-energise the political landscape in the country. While the recent general election has provided the most visible manifestations of this shift, social media platforms have been integrated into routinised political communication since the 2014 general elections, which swept the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to power. This shift builds on Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the BJP’s extensive use of social media in the run-up to the 2014 elections and during his first term in office.

Using social media to bypass traditional media and ignore critics, Modi has developed a distinct style of political communication that is interactive and continuous. His successful use of social media for political agenda building and policy crowdsourcing and publicity is evident in pan-India campaigns such as Swacch Bharat (Clean India) (Rodrigues and Niemann 2017) and the recently-launched Fit India Movement, a nationwide campaign, which encourages citizens to take up physical activity and sports in their daily lives. It was Modi’s phenomenal success in the 2014 general election that made other political actors in India to sit up and take notice of the game-changing nature of social media. With other political parties jumping on the social media bandwagon, the landscape of political communication in India has never been so heterogeneous, inclusive, fragmented, energetic, chaotic, creative, and equally polarising at the same time.

The next section discusses some salient elements of social media use by the BJP and the main opposition party, the Indian National Congress (or Congress, as it is simply known) during the 2019 general elections. This is followed by an examination of the (un)ethical dimensions of political communication adopted by these parties and/or their supporters, and the grave national security implications that came to fore due to the misuse of social media during the elections.

General Elections 2019: BJP Versus Congress Online

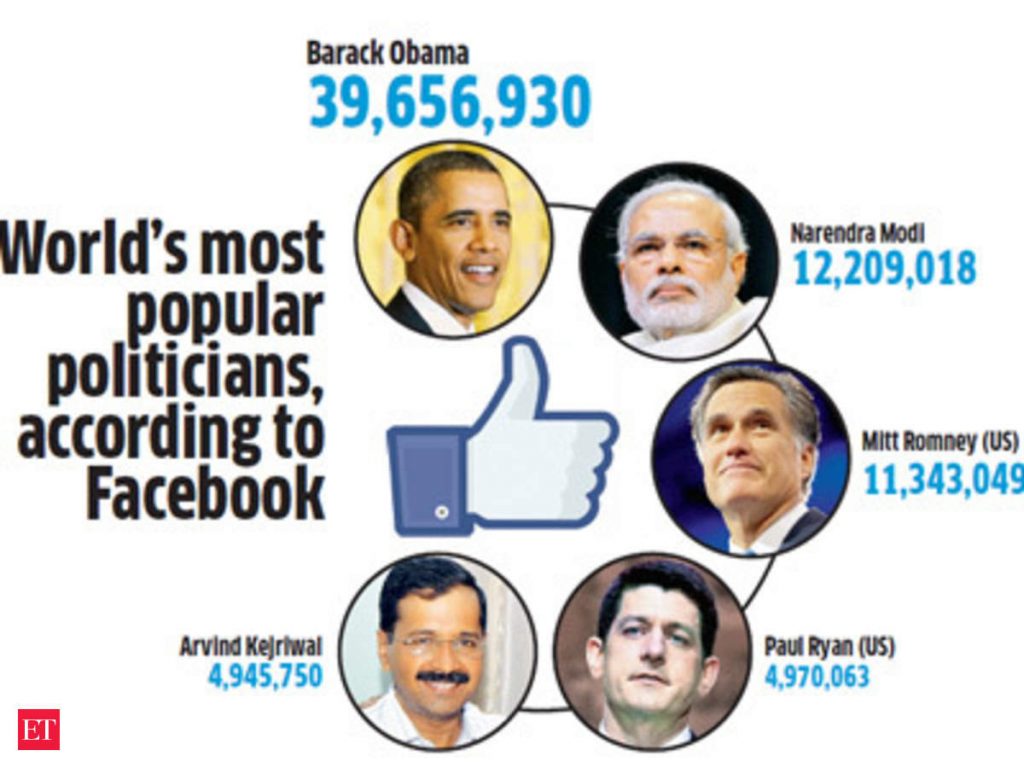

Within a month after becoming prime minister in 2014, Modi emerged as the world’s second most popular head of a state on Facebook (Goyal 2014), and in 2019, he has been the most liked leader on Facebook, with more than 43.5 million likes on his personal page and 13.7 million likes on his institutional Prime Minister of India page (Burson Cohn and Wolfe 2019). Similarly, through a skilful mastery of social media tactics on Twitter, including strategically crafted and inclusive messaging, use of selfies, celebrity involvement, and the “community action” (Pal, Chandra and Vydiswaran 2016) of his large numbers of followers to propagate his messages, Modi continues to remain a formidable force on the microblogging platform. In 2018, Modi was the third-most followed leader in the world on Twitter with 42 million followers on his personal account (@NarendraModi) and 26 million followers on his institutional account (@PMOIndia), which has the fourth-largest following globally (Burson Cohn and Wolfe 2018). In October 2019, Modi became the most-followed elected leader in the world on Instagram, with 30 million followers (NDTV 2019).

Other parties were late to the show, but quickly mastered several of the BJP’s tactics. Notably, the main opposition party, Congress, under the leadership of Rahul Gandhi in 2017 revamped party’s media policy with a new focus on social media, analytics, and crowdsourcing to compete with the BJP to garner attention in the cyberspace. The Congress made great strides in using social media, and despite the party’s social media strategy limitations (Khosla 2018), Gandhi steadily gained ground in the run-up to the 2019 general elections (Pal and Bozarth 2018). Through regular, humorous, and strategic engagement with audiences on social media, Gandhi was able to (re)brand himself as a serious political contender at the national level (Antil and Verma 2019).

Nonetheless, the BJP and Modi enjoyed a clear lead, and the BJP’s sophisticated information and technology (IT) cell made it possible. Many scholars and observers of this evolving landscape have focused on the narratives, imagery, interactivity, and other elements of political campaigning during the 2019 general elections. These are important areas of inquiry as social media emerged as a key battleground to mould public opinion and set an agenda. The role of social media in influencing political outcomes, however, is still being determined, with some preliminary research suggesting that social media’s propensity to determine voting behaviours was largely exaggerated (Daniyal 2019). As has been discussed widely, the BJP’s massive victory in 2019, in part, lay in the complementarity of its online and offline campaign strategies, and its robust grassroots support base and organisational structure.

While our knowledge of social media’s influence on political participation and political outcomes is still imprecise and incomplete, the ethical implications, however, are much clearer. The remainder of this article focuses on the ethical fallouts of the social media use during the 2019 general elections, its impacts on routinised political communication, and implications for safety and national security.

Ethics, Political Communication, and Security Implications

Social media has made Indian politics inclusive by allowing citizens, who were traditionally excluded from politics due to geography and demography, to gain direct entry into the political process. It has also allowed for a diversity of viewpoints and public engagement on an unprecedented scale. However, the 2019 general election also stands out for the new lows in public discourse, the pervasiveness of fake news and misinformation, and a routine flouting of ethical norms relating to political communication. Ethics in political communication, which has always been a complex issue (Denton 1991), is further complicated by the rise of digital technologies that are weakening traditional ethical constraints among all political actors—politicians, journalists and the mass media, and audiences.

The rise of polarising and divisive content has been a defining characteristic in the run-up to the 2019 general elections, with both the BJP and the Congress highlighting communal elements in their campaigning.[1] Social media has enabled a style of populist politics that is combative and personal, allowing hate speech and extreme speech to thrive in online spaces that are unregulated, particularly in regional languages and within private WhatsApp group chats. Sahana Udupa (2018, 2019) examines how hate speech and extreme speech have become routinised in online political communication and participation in India, its gendered implications, and the role of the Hindu right wing in producing majoritarian belligerence online. Sangeeta Mahapatra and Johannes Plagemann (2019) highlight how fearmongering and the politics of hate propagated by the BJP and the Congress have widened societal fault lines. Both parties and their proxies are also found to have shared large amounts of fake news and misinformation, which proved extremely difficult for fact-checking entities and vigilant citizens to process each case and to bring out truth (Rao 2019).

While name-calling, fake news, and other types of low-level discourse and unethical political communication have always existed, social media has undoubtedly exacerbated these problems to another level. Observers have lamented how political discourse in the country has plummeted to new lows, with misinformation, insults, and mudslinging becoming par for the course even among seasoned and top political leaders (Kumar 2014 and Misra 2019). The routinisation of such political discourse in a social media age, where such types of messages are magnified, shared, and replicated among populations with low-to-no levels of critical digital literacy is certainly problematic in its own right. These troubling trends raise new questions about the ethics of contemporary political communication, and the role of governments, corporations, press, and citizens in curbing unethical political discourse. Ironically, the role of all these actors is implicit, to some extent, in the spread of the problem. Therefore, they have to work together—along with academics, civil society, and ethicists—to stem routinised unethical communication and its detrimental effects via social media.

An area where unethical use of social media can have severe ramifications is national security and stability, as witnessed with the surge of fake news in the aftermath of the Pulwama attack in February 2019.[2] With fake news reaching a new high following the devastating attack on Indian paramilitary forces in Kashmir, fact-checkers noted the dangers of misleading posts that had flooded the cyberspace. The security implications of the rapid proliferation of misinformation post-Pulwama were manifold. Primarily, inflamed passions, sensational reporting, and political sloganeering due to the spread of fake news following Pulwama attack brought India and Pakistan to the brink of war. Facing intense public scrutiny online, Modi ordered airstrikes on alleged terror camps in Balakot, Pakistan, precipitating a series of retaliatory actions by both countries, which only ceased after Pakistan’s conciliatory gesture of releasing captive Indian Air Force pilot Abhinandan Varthaman. Here, outraged Indian netizens and a barrage of fake news played an instrumental role in triggering unprecedented hostilities between India and Pakistan (Bagri 2019), with security implications for the region as a whole.

The Balakot airstrikes and the subsequent release of Varthaman were widely celebrated on social media. This was quickly capitalised by the BJP to attach a national security dimension to its re-election campaign bid. The politicisation of Pulwama dominated social media and public opinion and subsequently played an important role in the BJP’s massive electoral victory (Bera 2019).

Another dangerous trend witnessed after Pulwama attack and Balakot airstrike was the spread of graphic images of violence by prominent persons, ordinary citizens, and media outlets to contribute to the prevailing rabble-rousing and rumour-mongering environment (Siyech 2019). Whether deliberate or otherwise, in an election campaign already rife with polarising content, false and misleading social media posts about Pulwama heightened jingoistic nationalism and communal tensions. Muslims and Kashmiris were vilified on social media, and in different parts of the country, Kashmiris were threatened, intimidated, and assaulted. Media investigations revealed that many of these campaigns of abuse were organised through WhatsApp and Facebook groups (Purohit 2019). Yet, another dangerous element was the labelling and trolling of more temperate voices or those who disagreed with the government’s actions as “anti-national.” This followed increasing popularity for the term, particularly among the supporters of the Hindu right wing, to use it to denounce individuals who disagree with their perspectives and brand them as traitors before subjecting them to violent trolling and to other forms of online abuse (Madan 2019).

The rumours and fake news that swirled around Pulwama/Balakot fall into a category of wedge-driving rumours that can have a long-lasting effect on the society, with the propensity to fuel social instability (Siyech 2019). In line with such fears, the no-holds-barred approach on social media produced unrestrained rhetoric that targeted minorities while influencing the government’s stand on foreign policy and national security issues—a practice that does not bode well for the democratic and ethical potential of social media in India.

Need for Caution

The advent of social media has changed how politics is being organised and conducted, as well as the nature of political communication in India. On the one hand, social media has allowed for the democratisation of politics and re-energised the political landscape. On the other, several ethical dilemmas arise with the involvement of political actors in the non-ethical uses of social media, compounded by the proliferation of social media among a largely digitally illiterate population. Particularly in the area of national security, political actors will have to weigh the political advantages against the very real security and human costs that would accrue from prolonged non-ethical uses of social media. The example of Pulwama/Balakot clearly indicates that unethical political communication via social media channels is not an issue that should be studied or tackled in isolation.

Sri Lanka provides a cautionary tale as to how divisiveness and hatred, propagated by political and religious leaders without impunity in cyberspace, can erode social cohesion and become a national security threat. In 2018, and yet again, in April 2019, after the Easter suicide bombings, the surge in fake news and hate speech exacerbated existing societal fault lines, resulting in deadly communal conflicts and riots. Given the serious implications of unethical political communication, political actors need to introspect further and focus on bringing back ethics to the table. As routinised unethical political communication has grave implications for politics as well as for social resilience and national security, the issue needs to be tackled on a war footing and through a multi-stakeholder approach. Political parties have a key role to play by reining in their proxies and supporters, and working with coalitions comprising of fact-checkers, civil society organisations, academia, think tanks, etc, to put ethical communication principles into practice in a social-media age.