In a region where Muslims have lived since well before the 16th century, the real question is why the remains of more ancient mosques have not been found?

By Amita Kanekar

In Goa, one is used to history lessons from the most unlikely of sources but that honour is now being extended to architecture as well. The latest wisdom is that the old Safa Masjid in Central Goa’s Ponda cannot have originally been a mosque. The reason offered by self-proclaimed experts is that talis, or water tanks, of the sort visible at Safa Masjid were built only at Hindu temples.

Mosques originated in Arab lands and Arab lands “had no water”, so there is no question of mosques having water tanks, they contend. Only Hindu temples had tanks, which means that that the Safa Masjid was originally a Hindu temple.

This kind of hate-inciting talk has become run of the mill these days. Indeed, if there was a competition for producing divisive rhetoric, these newly minted architectural experts would be beaten hollow by cabinet ministers in Goa’s Bharatiya Janata Party government, who seem to have no current challenges to deal with, given Chief Minister Pramod Sawant’s promises ad nauseum to restore “Hindu temples destroyed by the Portuguese”.

As if that wasn’t enough, Power Minister Sudin Dhavalikar in the wake of the Gyanvapi fracas in Varanasi declared that the Archaeological Survey of India must search for “shivlings in Goa’s destroyed temples”.

Even so, this latest attack on the Safa Masjid has a positive side: it has served as a reminder of the unique, and sadly overlooked architecture of the Goan mosque.

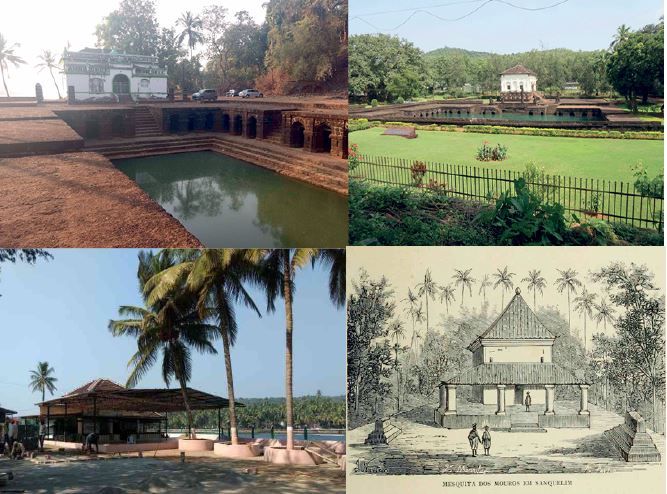

Contrary to the claims of these self-proclaimed experts, the architectural elements of the Safa Masjid are not unusual, nor is it the only mosque of its kind. In Goa itself, and less than 20 km away from the Safa Masjid, stands a remarkably similar complex on the banks of the Mandovi river in the village of Surla – the beautiful Surla Tar Masjid.

Smaller than the Safa Masjid and simpler in its ornament and detailing, this mosque complex is a similar arrangement of a relatively small building facing a large rectangular tank. There is also another and newer-looking dargah behind the old mosque building, which seems to have been built recently.

Although I have not been able to find much about the origins of this complex, its venerable age seems indisputable: its Pir Saheb was listed as one of the official affiliate deities of Siddeshwar, the chief deity of Surla village, when the Siddeshwar temple was registered in 1936.

Residents say that in earlier times, the Muharram celebration at the mosque used to be a major event involving all communities in the village. Now, however, the Muslim population of the village has declined and so has the event. But the mosque remains a part of the village’s Shigmo celebration, a traditional spring festival held in March in Goa.

The tank at the Surla Tar Masjid is similar to that at the Safa Masjid, lined with ogee arches along its laterite walls, which are interrupted by flights of stairs down to the water. The masjid building here contains a prayer hall fronted by a lobby, unlike the Safa Masjid, which only has a prayer hall. Both buildings are surrounded by a row of ruined pillars, clearly the remains of what would have been a surrounding pillared portico.

At the Corgao Dargah in Pernem, there is a similar double-massed form though it has been renovated using modern material – the central mass being the higher prayer hall topped by a sloping, tiled roof, and the lower being the surrounding portico with a lower lean-to roof. There is no tank here, perhaps because the dargah building almost edges the Terekol river.

At the Corgao Dargah in Pernem, there is a similar double-massed form though it has been renovated using modern material – the central mass being the higher prayer hall topped by a sloping, tiled roof, and the lower being the surrounding portico with a lower lean-to roof. There is no tank here, perhaps because the dargah building almost edges the Terekol river.

According to a study of the Safa Masjid by architectural historian Mehrdad Shokoohy in 1997, its original roof structure was different from the current one, which was constructed fairly recently by the authorities. A 19th-century image shows it roofless and in a state of neglect if not ruin.

The probable design of the original roof, a sloping one built of timber and topped by tiles, along with the arrangement of a central prayer hall surrounded by a portico, is close to the old mosques of Kerala, says Shokoohy, and is typical of mosques of the western coast.

But, through its high floor level, decorative niches, and ogee arches, it also resembles the architecture of the Deccan sultanates. The result is an architectural hybrid, unique to Goa and part of the region’s distinctive and creatively heterogeneous architectural traditions, which include churches, temples, and domestic architecture.

Mosques and water tanks

About the assertion that mosques have no water bodies, the fact is that mosques have always had water bodies. They might not always be large tanks and can vary from small pools to stepped wells or other forms, as can be seen all around South Asia and beyond.

In present times, these water bodies are often found to be replaced by modern water sources, especially in urban areas. Whatever the form, there was always a source of water, for the ritual ablutions that worshippers conduct before prayers. This is true of most spaces of worship, including Christian churches. So, it is not true that only Hinduism gives importance to water in a sacred space.

Discussing the tank of the Safa Masjid, Shokoohy points out that there are some mosque tanks in Karnataka’s Vijayapura, such as the Taj Khan Baoli, though these have plain walls, without the arches that edge the Goa mosque tank.

But Kerala also had decorated mosque tanks in the past, as is clear from a description by medieval explorer and scholar Ibn Battuta in the 14th century of a Jami mosque with a grand, ornate and stepped rectangular tank at Dahfatan, north of today’s Kozhikode.

Though probably larger, the Dahfatan tank sounds quite like the Ponda and Surla Tar tanks. Through the latter, it may have influenced the later Goan temple tanks as well, like at the Mangueshi temple in Priol.

Finally, a word about origins. The self-proclaimed experts point to the lack of knowledge about the origins of Safa and the unexplained origin date of 1560 offered by the Archaeological Survey of India as proof that something about the origins of this mosque complex is being hidden.

It is true that, like the Surla mosque, it is not clear when the Safa Masjid was built. There are no records or inscriptions relating to its foundation. Shokoohy, too, says he has not found any justification for the Archaeological Survey’s date of 1560.

But the lack of foundation records is fairly common for many buildings in South Asia and should not raise questions about the presence of this mosque. Goa has been the home of Muslim communities long before the region became part of the Deccan Sultanates in the 14th century. Muslim communities, especially connected to trade, are recorded as being based in the region from as early as the seventh century.

Besides this, Ponda became an important frontier town of Bijapur after the 16th-century conquest of Goa by the Portuguese, of the territories called the Old Conquests. It would become a part of Goa only with the expansions of the 18th century, the so-called New Conquests.

Far from being surprised at the presence of a mosque here, the real question should hence be: how come the remains of more ancient mosques have not been found in Goa?

One major reason would surely be the Portuguese destruction of all mosques they found. But the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party will not be heard talking of such destruction or the need to restore these mosques, nor of the lost shrines of other faiths, such as of Buddhists and Jains, or those of indigenous communities that are being destroyed even today. Restoration is only for destroyed Hindu temples.

It would make vastly more sense to protect and restore the heritage that remains, rather than look for what has disappeared. But maybe not political sense, especially with the kind of politics that offers little but an invented past and a violently divisive present.

Amita Kanekar is a novelist and an independent researcher in architectural history

Courtesy: the Scroll