As an aam aadmi I would not even be able to approach the residence gates of former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. But as a journalist and editor I had the unique privilege of travelling with Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and being present at the summit between him and General Musharraf.

By Rajan Narayan

Journalists live a double life! On their own with their limited and one-time pathetic salaries they would only afford to drink Hercules Rum and eat pav-bhaji or dal- bhaat. But in their professional capacity, they can lunch at The Oberoi and dine at The Taj hotels. Only because I was a journalist I had the opportunity to travel with Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to Brazil and Cuba. But on retirement the journalist, being the aam aadmi, nobody pays any attention to him because he is no longer useful for providing them publicity….

I COME from a very poor family. My father was a Lower Division Clerk in the Accounts Section of the Defense forces. Like many Goans his only ambition was to get a government job. But then as now without bribing politicians or with influence you could not get a government job. In Bengaluru where I spent my childhood, we used to eat only nachne (ragi) daily, it was working class people’s food. We ate it not because of the nutritional value of nachne but it was cheaper than rice and wheat and available in the ration shops. We also used to eat all the time something called “lapsi” which was made of boiled broken wheat.

If I had not taken up journalism as a job to dedicate myself to I would never have discovered the big bad world. Fortunately, I had a passion for writing. And right from the beginning, I was not afraid to ask questions to people in authority. Perhaps I was born a rebel. In Bangalore University the vice-chancellor, a Dr VK Gokak, started an official paper of the university. I decided with a few students to start a rival paper called “Retort” which translated to protest. But being students we were careful to put a chemistry retort. It was in “Retort” that I was later inspired to start my later tongue-in-cheek “Stray Thoughts” in the OHeraldo in Goa. But doing the “Retort” was way back in the 60s when I was doing my Bachelor’s at Bangalore University.

In 1967 I shifted to Bombay which became Mumbai. I enrolled for a Master’s course in economics in Bombay University. I was staying at the University Hostel and desperately needed a part-time job. I had gone with a friend of mine to the office of the Indian Express. My friend was working for Financial Express which was a sister publication of the Indian Express group. The news editor was very impressed that I was carrying on my shoulder a big bag of books. He asked me whether I had really read these books which were 600 to 1,000 pages. He asked me some questions about the books I had with me. Fortunately, I was able to answer his questions. He immediately offered me a job as a trainee sub-editor at a huge salary of Rs250 per month.

Back in the 1970s, Rs250 was considered equivalent to today’s Rs5,000! I took up paying guest accommodation, sharing my room with a friend Chandru Mirchandani at Kotachiwadi in Girgaon. My landlady was Claude Alvares’ mother who took a keen interest in her paying guests.

DOUBLE LIFE!

THAT’s when I discovered the double life that a journalist has to live in private. I could only afford to live on vada-pav or an omlet. I used to eat chola- batura from the gaddo outside Churchgate railway station. For dessert I would sometimes afford a Quality ice candy. I first got to know the power of being a journalist when I was asked to interview the maker of Afghan Snow (the company was established in 1909) which was much loved by women including my mother. The owner ES Patanwala was an early bird and wanted to see me at 9am in his office. Nobody else was interested in doing the interview and since I was the junior I was told to go.

Some of us reporters used to sleep in the office while doing the night or midnight or graveyard shifts. That morning I had got up late and even without brushing my teeth or changing my clothes I rushed to Byculla to keep my appointment with Patanwala. I was dressed in faded jeans and a purple kurta. I had a long beard. I must have looked like an awaara for when I reached the factory the watchman would not believe that his owner had invited someone looking like me. He was expecting somebody in a tie at least if not a suit.

But by raising my voice in English I managed to walk into the office of the managing director. There the secretary started putting a handkerchief to her nose while looking at as though I was some stinking being. She would not let me see her boss. Finally, the boss hearing the noise I made came outside in his impeccable three-piece suit and to the shock of his very stylish secretary, welcomed me warmly into his office with profuse apologies. During our conversation in his luxurious office he offered to pour out the best brandy into my coffee.

POOR STAFFERS

THIS was just the beginning. The Indian Express owner Ramnath Goenka didn’t believe in paying the staff much. His excuse was that we all got invitations from businesspeople who wanted publicity and we would staffers would be well taken care of by them. I learned that however big the industrialist they did not care about a journalist’s looks or attire but cared only about the publicity they could get in the Indian Express.

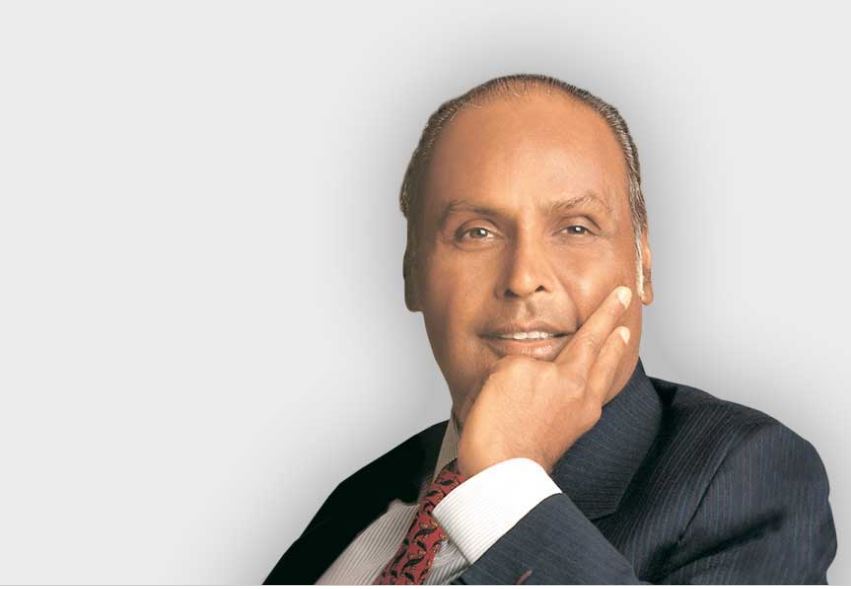

So I met the top industrialists of the 80s and 90s. I was the first to interview and write a cover story on a young Dhirubhai Ambani who was not afraid to bribe here and there while building his business empire. Dhirubhai clearly believed everyone had a price. He had silver slippers and golden slippers to give away or so speak. I also happened to teach his elder son Mukesh Ambani (today’s richest man in the world) conversational English when he was in the 12th standard.

I learned that Dhirubhai himself did not want publicity. I once told him that everyone was calling him a chor to needle him. He got very angry. He blamed his business rival Nusli Wadia of Bombay Dyeing for all his business problems. Ambani told me that Wadia was impotant. After a lot of pleading he agreed to do an interview with me but later on he did not like the article in which I had exposed how corrupt he was and tried to stop it from being published.

In fairness, it must be admitted that considering there were so many permits and permissions required to do honest business in those days, no honest businessman could survive. Ambani had the policy for some import machinery for making rayon and nylon fabrics changed only for 22 days. When the issue came up he told the press not to print it. He threatened my family. I made a police complaint. Finally, the political king of Mumbai then, Rajni Patel, brought about some kind of a conciliatory truce between Dhirubhai Ambani and the owner of the Business India magazine I was working for.

I REALIZED the power of being a journalist anew when I was interviewing the managing director of Associated Cement Company, S Krishna Murthy, who was from Tamil Nadu. I warned him that I was recording the interview. He thought that because both of us spoke Tamil I would be easy on him. I repeatedly warned him to call his public relations officer because he was talking nonsense. The MD started telling me how he could run a company where the production manager was 92 years old and the marketing manager 82 years old. He asked how could he run the company with these old Parsee idiots? When the issue of the Business India (where I was working later) came out carrying my interview quoting him, chairman JRD Tata was furious and immediately sacked the MD.

Thanks to being an editor I have met most of the older generation of top politicians in India and Goa. When I came to Goa in 1983 to start the English version of the OHeraldo, I celebrated my first birthday thanks to some business friends who organized a party for me – I was 24 years old. Earlier in my life and even before I became a reporter I had not even entered a five-star hotel in my life.

However, once a journalist and an editor I regularly lunched at the five-star luxury hotels of the Taj and Oberoi and appreciated premium Scotch all the time. The irony, such were our salaries, in my private day-to-day life I could afford to eat only dal-bhaat or batatawada-pau or pau-bhaji, washed down with army run. I also had family responsibilities to take care of early in my career when my father and elder brother had walked out on the rest of us.

MOST CHERISHED

PERHAPS my most cherished memory is that of travelling with former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in 2006 to Brazil and Cuba. Normally, a small press party accompanied the prime minister on his trips abroad and this trip I was invited, it was a long trip to Brazil first and then on to Cuba. The travel time from Bombay to Brazil is something like 28 hours even in a government state-of-the-art plane. In Brazil I met famous football players like Pele and Kaka. I visited Samba City where there schools teach young girls to dance for the Carnival dancing. From Brazil we went to Cuba and this was 30 hours flight. The plane flew over thick rainforest and we saw no naked ground at all.

Cuba was just like Goa and I stayed in hotel called Miramar. Cuba has the best rum, cigars, hospitals and free healthcare for its citizens. I sat in a bar made famous by the author Earnest Hemmingway who also invented the cocktail drink mojito. Another highlight of the trip for me was the meeting with General Pervez Musharaf of Pakistan who had tried to capture Indian territory at Kargil. Unlike Prime Minister Manmohan Singh who has no PR, General Musharaf embraced us and said “Hamare Bharat ke bhaiyo…” Never mind that he stabbed India in the back soon after.