Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

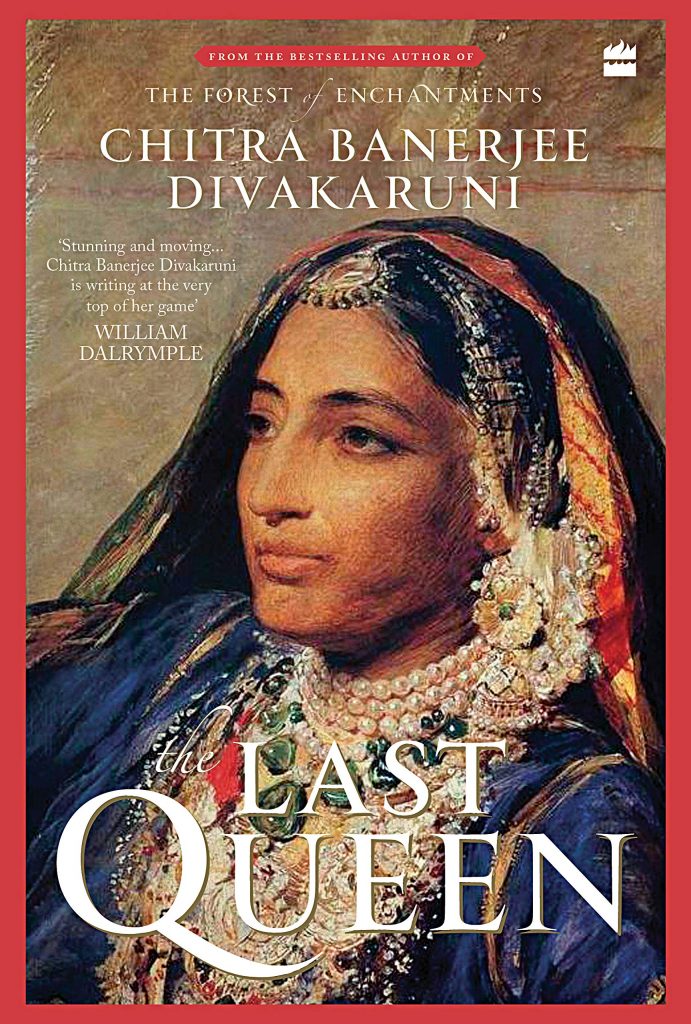

HISTORICAL FICTION GETTING POPULAR!

Mar 25 - Mar 31 2023 March 24, 2023IF you’re asking me nothing, nothing, nothing an replace the feel of a book in one’s hand…to read till sleep catches up! I’ve grown up with a book in my hand and listening to music on records of old. Nothing can replace that pleasure! Definitely not social media. To catch up with books making the news I sometimes catch up with the Out-of-Context Book Club at the Broadway Book Store in Panaji and this time on the eve of Women’s Day they were discussing Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s latest book “The Last Queen” on March 4, 2023.

If you have a yen for historical fiction this is one book you must catch up with. Historical fiction has become popular nowadays of course and one way of making us sensitive to history gone by be it fiction, half-fiction, or heavily laced with mirch masala in the telling of the narrative. As is the case elsewhere women of valour and grit have always been neglected by historians (except in rare cases) and I’m not sure if the late Khushwant Singh even mentioned the youngest Sikh queen of “Sher-e-Punjab” Maharaja Ranjit Singh in his magnificent ombudsman “History of the Sikhs”…namely Jindan Kaur, the daughter of the royal kennel keeper who became the king’s last queen and gave him son Dalip or Duleep Singh just a few years before he passed away in his 50s on June 27, 1839. The British were after riches of the Punjab empire of course and it was left to this feisty young last queen of the Punjabi empire, whose five year old son Duleep was made king by the Khalsa court, to take on the British whom her husband hated yet also entertained for diplomacy’s sake in his palace.

Jindan Kaur was 40 years younger than him but he married her after waiting for her to grow up to be 18 years and when she bore him a son she was in his heart forever or so speak! Never mind that it was barely ten years of a royal marriage and her son was barely a year old when Maharaja Ranjit Singh died. Life in the harem or zenana must have been tough for we know there were a hotbed of intrigue and power-mongering and the queen’s food had to be tasted before she was allowed to eat it…anyway, it’s a fascinating story to read, post-Ranjit Singh she had the gumption to do away with purdah and sati and fought the British from taking away her power…Maharani Jindan negotiated bravely through jenana politics with a few friends and many foes. She was the power behind the throne and it was Maharani Jindan Kaur who fought with her Khalsa army to keep the marauding British at bay…unafraid to speak her mind publicly, she certainly wielded power in her hands and was reportedly bold, rash and passionate and eventually in real life she escaped as a prisoner and was an exile in Nepal, later on in Britain (where she united with her “Britisher” son who had earlier been separated from her and sent to London where Queen Victoria kept an eye on him as he became a Christian, it’s a riveting story of many parts and sad betrayals).

According to the author this was a love story between a beautiful young commoner and a king whose eye she caught while during a Lahore outing his magnificent horse took a shine to the girl feeding him “gud” and he noted how kind she was to the animals…he married her after making her wait for two years more for her to turn 18 years and apparently remained a favourite with him till death do us part. Ten years of royal marriage, that’s it and she left a widow in her 20s…what happened afterwards makes for some poignant narrative full of heartbreak.

Interestingly, it is historically documented that Maharaja Ranjit Singh lived life maharaja size and had a harem of 20 wives and 23 concubines and it was your typical royal court with entertainment galore courtesy hundreds dancing girls. In these historical fiction novels it is always hard to tell where truth ends and fiction takes over!

But Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s “Last Queen” is worth reading even if it meanders in a first person novel, we do get a fascinating idea of a remarkable woman’s life and times in the royal court of the charismatic Maharaja Ranjit Singh of the Sikh Empire which the British so feared at one time and had to crack heads to bring it to its knees…er…if it ever did! Sikh history on its own is worth getting familiar with (seeing how to this day we see the zeal with which a separate state of Khalistan is sought). Nobody can take the Sikh “nation” for granted or so to speak.

I’M thinking what a grand history the Indian sub-continent has and so little of it has been brought alive in films, although I’m told now that the “The Last Queen” (it’s available both in hardcover and softcover, a 2021 publication) is turning into a film soon. Perhaps it was written to be turned into a film! It is historical novels like these which remind us that there was no India till recently and we were just a land of warring kingdoms with kings and queens when the Moghuls came to conquer and settle down, when the British came to rule and build their British empire and build their economy back home (never mind how many toiling and dying “natives” paid the price gallantly or bitterly)!

All this is also to say thank you to the Out-of-Context Book Club for highlighting “The Last Queen” and the discussion between various book lovers was quite hilarious for it entailed another time, other contexts and moral values which would seem so very weird and crazy for us today. I thoroughly approve of these book meets, the discussion not only focuses on the merit of reading books – some more than others – but also create a better understanding and appreciation amongst friendship between book-lovers old and young.

I do thank my friends Archana Nagvekar, Eric Pinto, Barkha Sharda, Indrani Basu, Valarie Freitas, Devayani Anvekar, some of the booklovers who make up the core team of the book club, for inviting me to the discussion. I also love making time to visit with Broadway Book Shop and just need an excuse to go!

ALL this reminds me to ask here how many queens of not-so-ancient Indian history you can recollect? They certainly made their presence felt in the times they lived in…go look up Rani Abbakka Chowta of Ullal (this warrior queen repeatedly defeated the Portuguese), Rajmata Ahilyabai Holkar (one of our most respected t Maratha woman rulers of Malwa), Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi (who hasn’t heard of her!), Rani Tarabai Bhonsle, Sethu Lakshmi Bayi, Rani Keladi Chennamma, Rani Durgavati, Naiki Devi, Rani Chennabhairadevi, Razia Sultana. Look them up please, one way or another they challenged the norms of their times to earn a name for themselves in history’s pages no matter how briefly.

Don’t know about you but I am going to read up a little more about all these women for I am seeking inspiration these days to live in my life and times when women are so much better of (except in Muslim countries like Afghanistan, Iran, North Korea, anywhere else?)…it was tough times for the women of old and it is tougher times for women today too when they’re coping with a myriad situations familiar and not so familiar.

On that note it’s avjo, selamat datang, poiteverem, au revoir, arrivedecci, hasta la vista and vachun yeta here for now.

—Mme Butterfly

An excerpt from `The Last Queen’ by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni (published by HarperCollins India, 2021 release)…

Scorpions

THREE WEEKS PASS. THE SARKAR neither comes nor sends any messages. My hopes sputter like a wick in an empty lamp. Days, I bear Manna’s invective, the growing desperation in his eyes. Nights, I dream of the Sarkar’s arm around my waist, his wine-scented breath. Soon, Jawahar will have enough money to

send me back to Gujranwala.

Then, when I’ve gouged the thorn of expectation from my heart, the Sarkar appears. He rides a different horse this time, a tall, red-brown animal who ignores me superbly when I run out to admire it. The Sarkar looks tired. He tells me he’s been preparing the troops, sixteen thousand cavalry, for a visit with the British. He met the governor-general, Bentinck himself, at Rupar by the Sutlej River.

He doesn’t apologize. He is, after all, a king. I should be thankful that he even chose to explain. I sense he doesn’t usually do so.

He describes the immense spread of the armies beside the Sutlej, greatest of our five rivers. The governor-general watching, stiff in his padded silk coat. Did the gora laat recognize the greatness hidden inside my Sarkar’s slender frame? Did he pay him due respect? I doubt it. When I ask how it went, the Sarkar smiles mirthlessly. ‘My Khalsa army performed many complex manoeuvres. Bentinck was impressed enough to remark that they put on a jolly good show.’ ‘But your purpose was served, was it not? He saw how strong we are.’ His eyebrows shoot up in surprise. ‘You’re the first woman to understand this.

My queens—even Mai Nakkain, the shrewdest—think I waste money entertaining the British because I love pomp and festivity. But you saw my true intent. Now the British will think many times before they try to cross into my territory.’

‘I’m glad your strategy was a success.’

‘For the moment. But the alliance I’d hoped for, a true partnership that might bring us peace… The British don’t want that.’ He shakes his head sadly. ‘Still, I must keep playing the game. Tomorrow Bentinck arrives in Lahore.

I am holding a banquet in his honour. I will give him many gifts. He will reciprocate, though with far fewer, because the British are tight-fisted. They came to this country as merchants. Their goal is to take from it everything they can. At the end of the visit, he will proclaim himself my lifelong friend—words that mean nothing.’

I’d give anything to wipe the despondence off his face. Hatred for the goras glows like a hot coal inside me.

‘The British have only one goal: to own all of Hindustan. They will not stop until it happens. But they won’t get my Punjab—not while I’m alive.’ He lets out a long breath. ‘Enough of such depressing talk.’ Patting the horse’s neck, he says, ‘This is Dildaar, very brave and steady. I want to take you for a ride on him. But could I have something to drink first?’

Luckily, I made some lassi earlier, churning the curds with black salt and crushed cumin the way we do in Gujranwala. I bring him a lota filled with the frothy liquid. He drinks it all.

‘Ah! I haven’t had lassi like this since I left my mother’s home.’

I can’t stop smiling even after I climb on because the Sarkar says, ‘You did that well. I think you’re a born horsewoman.’

Dildaar gallops very fast, but with the Sarkar’s arm around me, I’m confident.

We leap over a wall of stones. I laugh out loud, and the Sarkar laughs with me.

When the light turns soft, we dismount and walk along the edge of a cliff.

‘Sorry, there’s no banquet this time. I decided on this visit suddenly.’

Daringly, I say, ‘I’ve cooked saag and roti. If you don’t mind peasant fare, I’ll give you dinner when we get back.’

‘I’d love that.’

Below us rushes a great, galloping river. I stare at its roiling, mesmerizing

waves.

‘The Ravi,’ he says. ‘Beautiful and dangerous, like a headstrong woman. And like a woman, she drives me crazy sometimes. Once, I was returning from a campaign. We’d routed the Afghans after a long, dry fight in the desert. When I saw her foaming waters, and beyond it the walls of my beloved city, I couldn’t bear to wait for a bridge. I rode my horse into the river, even though my men yelled warnings. I intended to swim across, but the Ravi, she had a different plan. She grabbed me and swept me under. The horse swam away, but I almost drowned! It took four of my ghorcharhas to drag me to safety. When they got me back to the qila—looking more like a drowned rat than a triumphant conqueror —Wazir Dhian Singh scolded me roundly for endangering Punjab with my foolish risk.

‘Even now I remember how it felt, being tumbled head over heels by the dark, rushing water, my lungs burning. It was worse than facing a thousand armed horsemen.’

I draw a shuddering breath. How is it that with this man, I feel his pain in my body?

‘But it wouldn’t have been such a bad way to die,’ he muses. ‘Better than being stuck in a stinking sickbed.’

It takes me all my courage to touch his arm. ‘I’m glad you didn’t die. Not only for the sake of Punjab, but for my sake, too.’

He looks surprised. But after a moment he puts his hand over mine. He wears no rings except for one on his little finger, with a tiny red stone embedded in it.

Jawahar, who has been asking around, told me that in durbar, too, he dresses simply and sits on a plain kursi, even when foreign dignitaries come to visit. The throne is reserved for the Guru Granth Sahib.

‘I’m glad, too,’ the Sarkar says.

Tension hangs over us. His fingertips burn. I sway towards him.

He shakes his head as though clearing it of water. ‘Sun’s getting low. Time to get you back.’

ON THE RIDE HOME, I sit behind him, holding on tighter than I need to. I press my cheek against his back and breathe in his scent, sweat and wine and metal and a strong, wild fragrance which he explained was musk, his favourite perfume. Maybe he, too, doesn’t want the ride to end because he clicks his tongue to slow Dildaar down. The stars are shining all across the night sky when we reach the hut.

Before I can ask if he has time to stop for dinner, Manna is at our side, oozing solicitousness.

‘Greetings, Sarkar. I hope my daughter hasn’t been boring you with silly girlchatter.

Come, beti, I’ll help you down.’ I tell him I can manage, but he pulls at me until I lose my balance and feel myself sliding off the horse. He grabs me and staggers back, both of us almostfalling. ‘Oof, hazoor, look at this girl! She’s getting heavy. Too much for a poor old father like me. Take her off my hands, please! You’re a strong man, janaab, you can handle her weight!’

Is that a wink? Is Manna winking at Maharaja Ranjit Singh? Where’s Jawahar? I need him to come and drag Manna away before he says anything worse. ‘She comes from sturdy village stock. Strong and energetic, if you know what I mean. A virgin, too. She’ll keep you young for a long time.’

I want to bury myself deep in the earth. Waheguru, now the Sarkar will think we’ve been planning this together. That I was trying to seduce him. I begin to walk away, my steps stiff with mortification, the night blurred by my tears. He’ll never want to see me again.

The Sarkar’s voice stops me, cracking like a whip. ‘Have you no shame, Manna, talking about your own daughter as though she’s a bazaar dancer?’

He must have made a gesture of dismissal because Manna slinks into the house. I start to follow him, but the Sarkar calls my name.

I can’t bear to look at him now that everything’s ruined. But he’s the king. I must obey. He leans down and wipes my tears with his thumb. His touch is gentle. Why does it make me weep further? I am a stupid goat, like Manna claims. ‘Hush. Forget about your father. There’s a banquet in the palace tomorrow.

Remember, in Bentinck’s honour. Would you like to come? We can’t be

together. You’ll have to sit with the other women. But it’ll be something fine for you to see.’ be possible, especially after Manna’s crassness? I manage to nod.

But here’s a new problem: how does a girl tell a king she has nothing to wear?

He smiles. His beard shines, gossamer in the moonlight. ‘I’ll inform Guddan.

She’s the kindest of my queens. She’ll get you suitable clothes.’

How does he know everything I’m thinking? Before I lose my courage, I press my lips to his hand. For a moment, he’s very silent. Then he says, ‘Go inside, Jindan. Step carefully. ometimes scorpions come out at night, even inside the qila.’

He waits, still as carved marble in the moonlight, until I shut the door.