Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

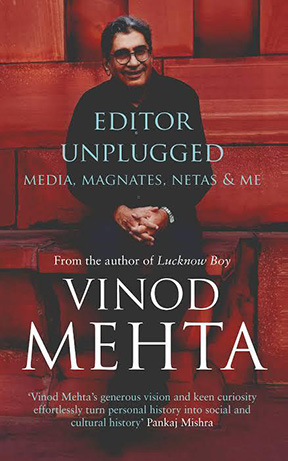

VINOD MEHTA’S `EDITOR UNPLUGGED’ From the author of `Lucknow Boy’

April 08- April 14 2023 April 7, 2023Books to read! Books Revisited! Books which count for something past, present and future!

Editor Unplugged’ is the second of Vinod Mehta’s biographical books, the first beingLucknow Boy’…Mehta lifts writing out of mundane boredom and offers sharp insights, wit and wisdom as he recounts his life and times in and out of a much celebrated media career first in Bombay and then in Delhi.

By Pankajbala R Patel

YOU may think this is a kind of dated book to recommend for reading but maybe not so — for this media insider’s view of how the Indian media works is still very much valid and more so. Not much has changed, if anything the situation is much worse with assorted media scrambling to stay alive and kicking or not kicking…that will have wait for a while till all the political muck of a failing democracy is cleaned up. Nobody knows how long it will take for India to arrive into the brave new world of a working democracy!

In this respect I have always thought the late iconic editor of Debonair, The Sunday Observer, The Indian Post… and finally Outlook – in a print media career of 40 years, has something to say which is worth knowing and meditating on. A true blue editor with a sharp eye sifting fact from fiction would be hard to find today – most have already compromised with their conscience and warmed up with the government of the day. A few sit on the fence waiting for more auspicious times, some of course are giving up the ghost in bits and pieces.

It is not often that media persons of any great worth have anything to offer at life’s end years, but one of my favourite editors, Vinod Mehta, walks in the footsteps of say a Khushwant Singh; he has a sense of humor as well as irreverence for those chasing power and pelf without any conscience or respect for the people in whose name they are “public servants” but in name only, “public masters” would be more appropriate nowadays.

For all interested in the Fourth Estate as a pillar of democracy must read this book titled Editor Unplugged, Media, Magnates, Netas & Me’ (Penguin Viking, hardcover, 2-14, Rs599) which is very readable as are all of Vinod Mehta’s books (he has earlier books on Meena Kumari and Sanjay Gandhi which he wrote during his Bombay or Mumbai years, before he washed the dust of the megapolis in favour of editing the Outlook in Delhi for over a decade before retiring gracefully to write his memoirs first in Lucknow Boy (2011) and now in continuityEditor Unplugged.’ The Outlook’s expose of the Niira Radia scandal impacted his editorship hugely and presumably led to his early retirement from actively editing the weekly. For Vinod Mehta it was a time to look back, look forward, writing his memoirs were perhaps a sort of payback time for here he gives an inside understanding of business biggies he had to deal with like Ratan Tata, Mukesh Ambani and others. He also offers us valuable insight into some of our favourite personalities like Khushwant Singh, Arvind Kejriwal, Rahul Gandhi, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Sachin Tendulkar, Rajdeep Sardesai, Arundhati Roy, Ruskin bond and many more, some of whom he considered his personal friends.

FROM BLACK & WHITE

MEHTA lived at a time when old world black and white print journalism was giving way to today’s razzmatazz genre of colourful audio-video journalism – today’s playing fields of media are in hi fi electronic and digital fields, which can make for some mindboggling manipulation and superimposition to hoodwink readers! Fake news is getting bigger and bigger and readers have to be several notches ahead to tell truth from lies and make-belief!

“Editor Unplugged” makes for both amusing and disquieting reading and gives one a glimpse of how the face of society has been changing post-Rajiv Gandhi era – for the better or for the worse, we are not quite sure yet given today’s steeped in defection politics and anarchical mayhem. The author’s story-telling is enriched with favourite quotes and anecdotes gleaned from his own reading and learning over years and this makes the narrative come alive in chapter after chapter.

If you’re asking me the Vinod Mehta books makes for a perfect re-capping of what has led us to today’s political and social scene scenery; you must read him all the more if you’re a media person or a politician! A Business Standard review of the book describes him as “A man who is widely known for many things: wit, an instinctive sense for story…(and) a suspicion of power.” His books facilitate a better understanding of how far contemporary media has travelled and offers sharp and piquant insight into “media, magnates, netas and me” — almost right up to the present where so many of the players are still alive.

Excerpted from `Editor Unplugged’ by Vinod Mehta…

The Dynasty

When I joined Debonair as editor, several hurdles awaited me. However, I did not anticipate which one would cause me the greatest difficulty. My expectation was that the nude centre spread would be my Mount Everest. Well, that is how I began, but when it quickly dawned on me that Sharmila Tagore or Miss India could not be persuaded, I gave up. Occasionally, a Katy Mirza would come my way; however, it was mostly unwashed hippie girls, living in Stiffles Hotel, who agreed to shed their clothes for Rs250.

No, the tallest hurdle was Politics – how to write it, how to evaluate it, how to commission it and finally, how to decide how much of the stuff should be included in a journal whose reason for existence had nothing to do with current or non-current affairs.

Given the country’s landscape in 1974, I had no option. Politics to the left, politics to the right, politics to the centre surged out into the public domain and dominated public discourse. The Nav Nirman movement, led by Jayaprakash Narayan (JP) crusading against the Indira Gandhi regime, was growing rapidly. Mrs Gandhi, under siege, countered with an underground nuclear test at Pokhran, hoping the dhamaka would divert attention from JP’s anti-national’ activities. For the common man, irrespective of his ideological loyalties, 1974 could safely be described as an intensely political year, a harbinger of the shameful Emergency twelve months later. What do illiterates do to overcome their illiteracy? They read a book. I read several in the course of my self-education on a subject called politics. The competition was awesome. The Bombay-based editors were not to be trifled with. Sham Lal, Girilal Jain, V.K. Narasimhan, represented the Bombay trio; and the ones stationed in Delhi were equally formidable. If memory serves me right, most of these gentlemen wore reading glasses as thick as boulders. When seen in public, which was rare, they carried books which could be used as door-stoppers. These were serious men who took writing on politics very seriously. Their social life consisted of frequent visits to bookshops . In Mumbai, Strand Book stall, run by the likeable and helpful Mr Shanbhag, was their preferred haunt. Unreliable tittle-tattle says that Messrs Sham Lal, Girilal Jain, N.J. Nanporia could spend anything from two to four hours browsing through the latest Andre Malraux. Refreshments were supplied by the management, and free books in the hope that they would be reviewed. These were the worthies I had to compete with, if you will pardon the expression. One day, I met Girilal Jain and confided in him my problem.To write on politics,’ he declared, you first have to understand the grammar of politics.’ What the hell is the grammar of politics? The phrase stuck in my throat. I hated it. In forty years of journalism, I have never used it. I could write, read and speak Macaulay’s recommended language for aspiring clerks reasonably. Consequently, I started reading both the Delhi and Bombay editors with care. Frankly, it was not easy. I had difficulty getting beyond the first two paragraphs. The text may have been profound, scholarly and supremely in the national interest, but it was wittingly dense and convoluted. One could read an entire piece of 100 words and ask: “What was that about?” (To be fair, Girilal Jain, once he picked up a cause – Hindu nationalism – became at once provocative and engaging, while Sham Lal mentored a line of journalists who reached high places.) As chance would have it, just before joining debonair I had interviewed Khushwant Singh, then editor of the Illustrated Weekly. I asked him to respond to the criticism of the traditional editors that he was a shallow person whose political writing could be situated between the inconsequential and the titillating.Have you tried to read Sham Lal?’ he asked. He is unreadable.’ To strengthen his case, he said the most prestigious foreign publications, like the New York Times and the Guardian, regularly invited him to contribute political columns.They don’t ask Sham Lal,’ he said bitchily. Clearly, not much love was lost between the shallow and the thoughtful.

Torn between two polarized propositions, I thought I should investigate the matter for myself.

Fortuitously, at that moment, a new genre dubbed New Journalism surfaced. The appellation is attributed to American journalist tom Wolfe, and its foremost practitioner proved to be Norman Mailer, who also wrote fiction. In 1960 Mailer published a 9000-word essay on Esquire magazine eccentrically titled, Superman Comes to the Supermarket’. Susceptible to unorthodox influences, I took to Mailer at once. He broke all the rules of journalism as we knew them and yet his piece was unputdownable. The author metamorphosed into the central figure of a narrative objectivity was cavalierly jettisoned. He also made generous use of the pronounI’.

Here is a Mailer covering the 1960 Democratic Convention in which John Kennedy was a strong contender for the ticket: And suddenly I saw the Convention. It came into focus for me, and I understood the mood of depression which had lain over the Convention, because finally it was simple: The Democrats were going to nominate a man who, no matter how serious his political dedication might be, was indisputably and willy-nilly, going to be seen as a great box-office actor, and the consequences of that were staggering and not at all easy to calculate.’ Mailer took the journalism manual and tore it up. He mixed reportage, opinion, conjecture and prejudice. C.P. Scott, who gave the profession its stone-written mantra,News is sacred, comment is free’, was not available for comment.

In 1973, Tom Wolfe edited an anthology of New Journalism. In the introduction he observed,

The voice of the narrator was one great problem in non-fiction writing. Most journalists, without knowing it, work in a century-old British tradition in which it was understood that the narrator should assume a calm, cultivated and in fact, genteel voice…Understatement was the thing. You can’t imagine what a positive word understatement was among both journalists and the literati ten years ago.

Wolfe continued,

There is something to be said for the notion, of course, but the trouble was that by the early 60s, understatement had become an absolute pall. Readers were bored to tears without understanding why. When they came upon the pale, beige tone, it began to signal to them, consciously, that a well-known bore was here again, the journalist, a pedestrian mind, a phlegmatic spirit, a faded personality, and there was no way to get rid of the pallid little troll short of ceasing to read. This had nothing to do with objectivity and subjectivity or taking a stand or commitment – it was a matter of personality, energy, drive, bravura…style in a word.

New Journalism, Old Journalism, one thing got deep into my skull: whatever sage and urgent message I wished to communicate, I had to ensure I did not bore the reader with the gravitas of the message, and also did not feel shy in trying to add some style to my prose. We journalists are fortunate to be journalists. Our readers believe we can deliver privileged information. Nevertheless, we have to mandate for self-indulgence or abstraction – a self-indulgence which snobbishly demands that serious writing must be written solemnly. The trick, of course, is to deal with heavy subjects lightly. It is something I am still working on.

If there is a lesson I have learnt in forty years of political writing, it is that political writing is no different from writing on Bollywood. (Who said politics is showbiz for ugly people?) colour, fact, atmosphere, speculation, bias, a jolly touch, must be judiciously mixed to ensure your audience stays on the page.

As he stares into the blank screen, the political journalist, indeed all journalists, must remind themselves, I am writing for the reader, not for the foreign minister.’ The novelist Stephen King, who knows a thing or two about holding the reader, says,One of the really bad things you can do to your writing is to dress up the vocabulary, looking for long words because you’re maybe a little bit ashamed of your short ones. This is like dressing up a household pet in evening clothes. The pet is embarrassed and the person who committed this act of premeditated cuteness should be even more embarrassed.’

At the rookie age of twenty-six, I took tutoring from Khushwant Singh, S. Mulgaokar, George Verghese, Normal Mailer, Tom Wolfe, James Cameron, among others. Besides, my comfort level with this type of journalism was high since I am a naturally opinionated person. Early on in my career, I attempted political writing in a cool, anonymous, impersonal voice. What emerged needed to be consigned to the wastepaper basket.

The voice’ is for the individual to find. You can’t fake it, you can’t copy it. It has to be your own. How you acquire it is something of a mystery. But acquire it you must. It will not come if you lie, evade, tell half-truths…George Orwell put it succinctly,The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms.’

For instance, it would be virtually impossible for me to write a coherent piece defending the RSS or attacking the indispensability of secularism in our republic or praising George Bush. Toadies can do it but a journalist with some integrity will find it difficult.

One you have your voice, good, bad or indifferent, you can write text which, if nothing else, is honest. And your own.