Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

READ HISTORY, READ INDIAN HISTORY, READ WORLD HISTORY.… To have a future and not a repeat past!

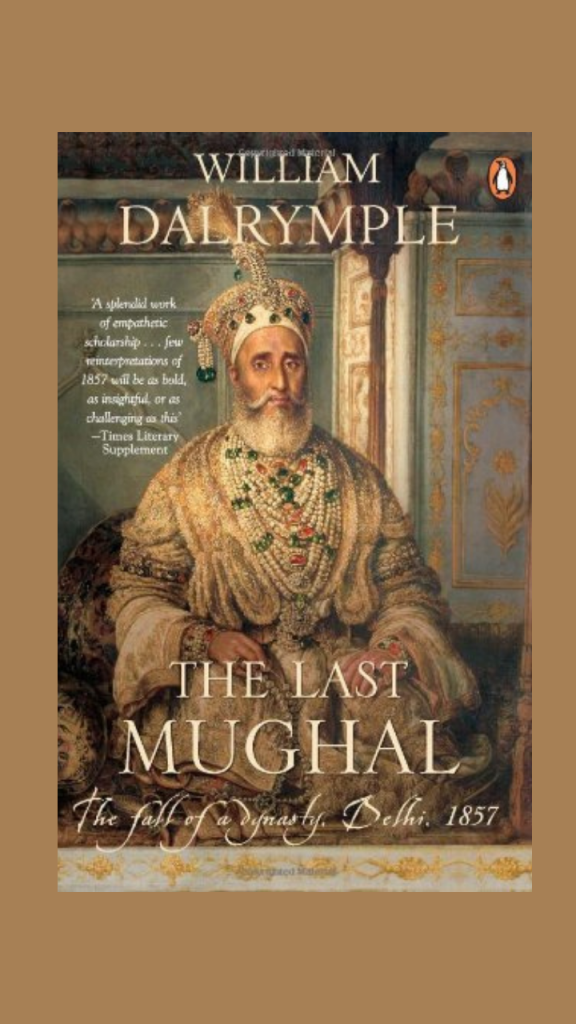

April 01-April 07 2017, April 29- May 05, 2023 April 28, 2023`The Last Mughal, The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi, 1857’

By William Dalrymple (Penguin softcover, Rs699).

IT’S so rewarding to be back to reading! For a while I had just given up on good old-fashioned reading with the book in hand, never mind if one falls asleep while reading it…reading history can make you yarn and fall asleep faster! But not this book on my mind currently: William Dalrymple’s “The Last Mughal, The Fall of a Dynasty” which recounts the rise and fall of the last Mughal dynasty’s emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar II…and along with it we get a graphic description of life and times of the city of Delhi, once a royal Mughal city and then it turned British when the British East Indian Company moved to Delhi from Calcutta to rule its vast empire.

How the British dealt with the then Indian rulers Hindu or Muslim is a fascinating narrative because in the end although they had to deal with various famous and infamous British “servants” posted to supervise India…the nitty gritty of diplomacy, frustration, ambition, scheming harem concubines and too many wives…it’s all here for our understanding in Dalrymple’s magnum opus of a book, non-fiction, not spiced up with mirch masala. So weary and tedious reading at times but altogether so profoundly enlightening and educative, you’ve got to read it patiently.

Here’s the unvarnished truth and what a bleak, grim narrative comes through as we see how the royal romances and grand lifestyles turn shoddy, pathetic, poignant in turn…but still struggles to survive with dignity with whatever resources of a once fabled wealth is left (the bulk of it squirrelled away by who else but the British Raj). This is the political world of old and we need to understand it.

After reading this book the sorrier I am sorry that the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi sees it fit to remove Mughal history from the NCERT textbooks of our children – what half-educated arrogance and lop-sided tunnel vision rules us today! It’s a version of modern-day imperial arrogance which I pray will end one of these days before the real horrors of tit-for-tat bloodshed commence anew with a repeat of stale narratives…

Who is going to make a clean sweep of the hellish life imposed on aam aadmi today with superficial and hypocritical promotional stances so visible around us… preaching something contrary but so clearly indicates that a mass of people are pretending to be deaf, dumb and blind out of disbelief and fear – sitting on fences forever! Hey, this is a courageous sub-continent which made it through thick and thin and to be described as a great civilisation! Remember that.

But this is to say after an admittedly quick reading of William Dalrymple’s “The Last Mughal” I’m more than ever convinced our Indian children need to study Mughal literature to be clued up on what Moghul giving way to British history was all about – put history in perspective so that we perhaps reap a happier future and not go in for repeats of history in various more sophisticated vendettas which have humankind have surely outgrown now?! Or are out minds still bogged down by retrogressive medieval ways of thinking despite the advancement of science and technological material comforts?

The book has been so meticulously researched by one of our most conscientious writers who though a Scotsman may as well be half-Indian! He is the author of five books of history and travel, including the highly acclaimed award-winning bestseller “City of Djinns”, also read “White Mughals”…the much celebrated Dalrymple is married to artist Olivia Fraser and loves to travel with his three children, dividing his time between London, Scotland and Delhi.

Find time to read his books for they offer more than just a fleeting glimpse of history, his is no grandstanding writing but one which is most detailed with research enough to refresh the mind with fabulous insights! “The Last Mughal” reveals the sad story of royal betrayals, debauchery, violence…and yet there’s a side to it all which also speaks of the renaissance of learning, literature, poetry, wisdom, faith, real romance and trash and how it all got corrupted through the valiant errors of judgement in personal as well as empire politics…and just passing time which waits for no one to set anything right.…hell’s bells, by now someone should have make a television series on the Mughal dynasty in India! Say, along the lines of Turkey’s “Magnificent Century” (recounting the life and times of Sultan Suleyman)! William Dalrymple’s “The Last Mughal” offers valuable reference material to work on.

Read this book if you also want to get an idea of what Delhi used to be like once upon a time — but not too far back in history, closer to our times! If you’re asking me all India’s Mughal monuments, literature, cultural and religious moorings along with whatever defines three centuries of Mughal history in the sub-continent should be retained, show-cased, appreciated, for the world to learn valuable lessons. I guess nobody is listening here!

ON that note this is just to note that my life has become one round of festivals in Goa good, bad and ugly and I’m trying desperately to get back to reading some of my favourite books of yesteryear and today…also catch more films ESG’s Cine Club, may be travel a bit if I can, haven’t done it for so long in recent years that I’ve almost forgotten the joys of discovering new places! Also almost three-quarters of me is almost gone now; nevertheless I will always say books, films and travelling around is the most valuable education anyone may invest in to be fully educated human beings. And so did a few editors I once worked with in Mumbai-that-was-Bombay…on that note its avjo, selamat datang, poiteverem, au revoir, arrivedecci, hasta la vista and vachun yeta here for now.

—Mme Butterfly

Excerpted from `The Last Mughal, The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi, 1857’ by William Dalrymple…. (from author’s Introduction)

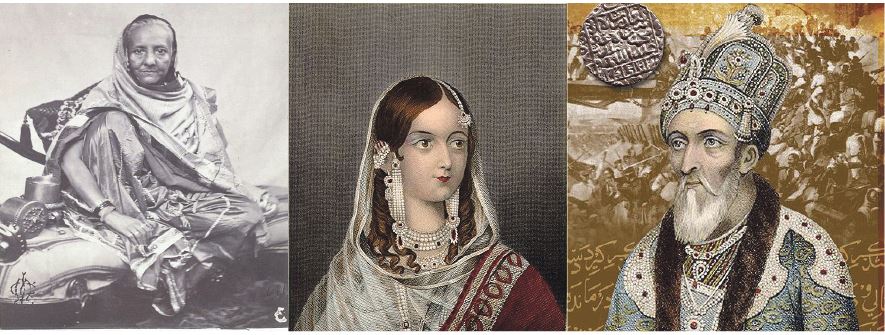

ALTHOUGH Bahadur Shah II, the last Mughal, is a central figure in this book, it is not a biography of Zafar so much as a portrait of the Delhi he personified, a narrative of the last days of the Mughal capital and its final destruction in the catastrophe of 1857. It is a story I have dedicated the last four years to researching and writing. Archives containing Zafar’s letters and his court records can be found in London, Lahore and even Rangoon. Most of the material, however, still lies in Delh, Zafar’s former capital, a city that has haunted and obsessed me for over two decades now.

I first encountered Delhi when I arrived, aged eighteen, on the foggy winter’s night of 26 January 1984. The airport was surrounded by shrouded men huddled under shawls, and it was surprisingly cold. I knew nothing at all about India.

My childhood had been spent in rural Scotland, on the shores of the Firth of Forth, and of my school friends I was probably the least well-travelled. My parents were convinced that they lived in the most beautiful place imaginable and rarely took us on holiday, except on an annual spring visit to a corner of the Scottish Highlands even colder and wetter than home. Perhaps for this reason Delhi had a greater and more overwhelming effect on me than it would have had on other more cosmopolitan teenagers; certainly the city hooked me from the start. I backpacked around for a few months, and hung out in Goa; but I soon found my way back to Delhi and got myself a job at a Mother Teresa’s home in the far north of the city, beyond Old Delhi.

In the afternoons, while the patients were talking their siesta, I used to slip out and explore. I would take a rickshaw into the innards of the old City and pass through the narrowing funnel of gullies and lanes, alleys and cul-de-sacs, feeling the houses close in around me. In particular what remained of Zafar’s palace, the Red Fort of the Great Mughals, kept drawing me back, and I often used to slip in with a book and spend whole afternoons there, in the shade of some cool pavilion. I quickly grew to be fascinated with the Mughals who had lived there, and began reading voraciously about them. It was here that I first thought of writing a history of the Mughals, an idea that has now expanded into a quartet, a four-volume history of the Mughal dynasty which I expect may take me another two decades to complete.

Yet however often I visited it, the Red Fort always made me sad. When the British captured it in 1857, they pulled down the gorgeous harem apartments, and in their place erected a line of barracks that look as if they have been modelled on Wormwood Scrubs. Even at the time, the destruction was regarded as an act of wanton philistinism. The great Victorian architectural historian James Fergusson was certainly no whining liberal, but recorded his horror t what had happened in his History of Indian and Eastern Architecture: those who carried out this fearful piece of vandalism’, he wrote, did not even thinkto make a plan of what they were destroying, or preserving any record of the most splendid palace in the word world…The engineers perceived that by gutting the palace they could provide at no expense a wall around their barrack yard, and one that no drunken soldier could scale without detection, and for this or some other wretched motive of economy, the palace was sacrificed’. He added: `The only modern act to be compared with this is the destruction of the summer palace in Pekin. That however was an act of red-handed war. This was a deliberate act of unnecessary vandalism.’

The barracks should of course have been torn down years ago, but the Fort’s current proprietors, the Archaeological Survey of India, have lovingly continued the work of decay initiated by the British: white marble pavilions have been allowed to discolour; plasterwork has been left to collapse; the water channels have cracked and grassed over; the fountains are dry. Only the barracks look well maintained….

(from chapter The Last of the Great Mughals)

By 1862, Zafar had reached the grand old age of eighty-seven. Even though he was weak and feeble, and although doctors had now been expecting his imminent demise for some two decades, he still showed no signs of succumbing to their predictions, beyond feeling ill with paralysis at the root of the tone’. In late October 1862, however, at the end of the monsoon, Zafar’s condition became suddenly much worse: he was unable to swallow or keep down his food, and Davies wrote in his diary that the tenure of his life was nowvery uncertain’. The old man was spoon-fed on broth, but by 3 November found it increasingly difficult to get even that down. On the 5th , Davies wrote that the Civil Surgeon does not think Abu Zafar can survive many days’. The following day, Davies reported that the old manis evidently sinking from pure decrepitude and paralysis in the region of his throat’. IN preparation for the death, Davies ordered that bricks and lime be collected, and a secluded spot on the back of Zafar’s enclosure was prepared for the burial.

After a long night’s struggle, Zafar finally breathed his last at 5 a.m. on the morning of Friday, 7 November 1862. Immediately the machinery of the Empire swung into action to make sure that the passing of the Last Mughal would be as discreet and uneventful as possible. Zafar’s death may have marked the end of a great ruling dynasty 350 years old, but Davies was determined that as few as possible would witness this sad and historic moment. All things being in readiness,’ wrote Davies,he was buried at 4 p.m. on the same day at the rear of the Main Guard in a brick grave, covered over with turf level with the ground.’ Davies noted how his two boys and their father’s man servant attended the burial, but the women, in accordance with Muslim custom, did not.

A bamboo fence surrounds the grave for some considerable distance,’ he concluded,and by the time the fence is worn out, the grass will again have properly covered the spot, and no vestige will remain to distinguish where the last of the Great Moghuls rests.’

The following day, Davies wrote his official report on the demise of his charge. This event made very little impression either on the relatives or on the Mahomedan population of this town,’ Davies noted with satisfaction.Probably about a couple of hundred spectators assembled at the time of the funeral, but this even was occasioned in a great extent by idlers coming from the neighbouring Sudder Bazar to town to see the Races which were going on that afternoon near the prisoners’ quarters.’

The death of the ex-King may be said to have had no effect on the Mohamedan part of the populace of Rangoon,’ he added,except perhaps for a few fanatics who watch and pray for the final triumph of Islam.’