The memoirs of Valmiki Ram by Lindsey Pereira is a book of gods and goddesses and the reality at ground level. Do gods feel a sense of failure or fear when terrorist acts take place. The author has ventured into the emotions of gods.

By Sayari Debnath

Do gods feel regret, a sense of failure, or fear when they see the monstrosity they have set into motion? Are they infallible, do they pay for their shortcomings, or do their lives ever end in tragedy? The answers depend on what (or who) you think god is. Organised religion has done a spectacular job of making god human.

Think about it – yes, god is supposed to have superpowers and hordes of loyal followers, but just like you and me, god’s existence is full of challenges. There are bad guys to defeat and teach lessons, good guys to reward and be grateful for, existential doubts about one’s purpose, and the desire – however small – to be remembered. These absurdities of life have bogged down mortals and they haven’t spared the gods either.

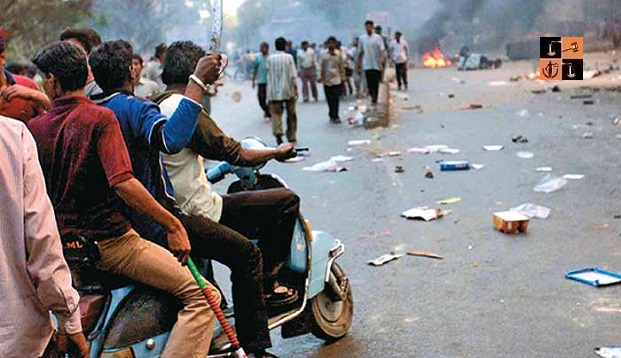

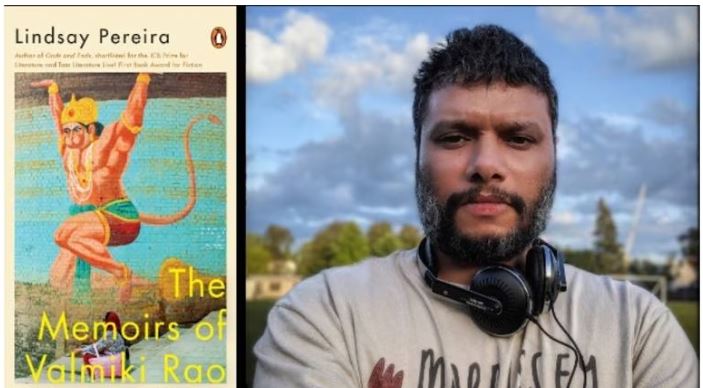

Lindsay Pereira’s latest novel, The Memoirs of Valmiki Rao, is about the failings of gods and their fanatic believers who very easily turn into blood-hungry mobs. Now in his 70s, retired postman Valmiki Rao remembers the Mumbai riots of 1992-93 – the fiery months of madness that the grand metropolis of Mumbai seems to have so conveniently forgotten. But people like him – those cornered into dilapidated chawls, fighting over shared latrines, and oppressed by the city’s ever-rising expenses – do not forget so easily. This is Valmiki’s story and Ramu, Janaki, Ravi Anna, Lakhya, Bantya, Manisha, Surbha, and Sundar are the key characters. As are politicians in Delhi and Mumbai who are pulling the strings of this show.

The fight for ‘Ayodhya’

The similarities with the Ramayana are delightful – the cleverly constructed names and relationships, the petty politics of a self-contained world, and the consequences of stepping out of line. Ganga Niwas – much like Ayodhya? – is a place where Christians, Sikhs, and Muslims do not exist. The different castes and cultures mingle together, but sharp lines are drawn when questions of holy matrimony arise. Everyone sticks to their own kholi and they have accepted that small people like them should not demand more space in the already suffocating city of Mumbai.

Children are born, grow up, drop out of school, join the Shiv Sena shakhas, and turn into louts – that’s the normal course of life in the 1980s. The boys are transformed into “god’s holy warriors” – never mind that they don’t ever visit the temples in their neighbourhood, but a passionate fire rages in their hearts for the Ram temple in Ayodhya, gently stoked by the Sena leaders. They have never seen it and perhaps never will, but they know Muslims are the enemy, the Babri Masjid has swallowed up a temple and the Hindu pride, and they must “wake up” and take back – with force, of course – what has always been there. High rates of unemployment and undignified standards of living are twigs and leaves that ensure the fire burns bright and high.

Elderly residents like Valmiki Rao know it’s a futile quest, not because Ayodhya is far away and Hindus are forgetting their “dharma”, but because he has lived long enough to know that Indians are weak people and we are weighed down with hatred – we do not question, we are meek as sheep, and cruelty instead of rationality whets our collective imagination. Ours is a story that is doomed from the start.

Valmiki Rao remembers how the ominous colour of saffron spread through Mumbai. Kesari-coloured flags appeared outside everyone’s balcony, shouts of “Jay Shri Ram” started to become common in a land otherwise known for its faith in Ganesha, and more and more local politicians (or goondas as he calls them) began pouring money into celebrating festivals and rewarding small-time hooliganism. Ganga Niwas and Mumbai were changing, and none of them could do anything about it.

An eternal fire

In the middle of this, Ramu and Lakhya Shinde are the only glimmer of hope. It’s true that unfortunate family circumstances made the boys drop out of school and join the local Shakha, but what did not change is innate decency and goodness in these boys. They were not like the others – bribing and blackmailing, badmouthing Muslims, and barbarism were not in their blood. They helped old women carry groceries, were polite to the elderly, and Ramu’s love for Janaki was nothing short of complete devotion.

The two boys were also kind to their stepbrother Bantya and reluctantly took on the responsibility of their widowed stepmother, Kavita. The other parents of Ganga Niwas could only pray that they be rewarded with such virtuous sons in their next lifetime.

If you are familiar with the Ramayana, you would know that this utopic bubble would soon burst. Right across Ganga Niwas is Sri Niwas, another nondescript chawl full of ruffians and thugs and their fearsome leader Ravi Anna, a Tamil outsider who is slowly reaching for Mumbai’s throat. He happens to be in love with Janaki too and will do anything to have her. The slow-spreading fire of Hindutva only helps his cause and, though not exactly religious, it doesn’t stop Ravi Anna from making full use of riot-stricken Mumbai for his personal vendetta.

As tempers flare on both sides, the minions of Ravi Anna and Ramu find themselves in an epic face-off. There’s stealth and there’s plenty of action, there’s a desire to do what feels right, and there’s an insatiable thirst for revenge. The Valmiki of the Ramayana and the Valmiki of Ganga Niwas remember and write about the battles as they imagine what was said, the grand lines that flew out of each man’s mouth, and the women who witnessed it in silence. Everyday vices – lust, greed, and hunger for power – light the fire and burn Sri Niwas to ash.

But it’s not just Ravi Anna and Sri Niwas who fall from power – the fire spares no one. The virtuous Ramu is horrified when he realises that the fight to free Janaki from Ravi Anna’s clutches has turned into a juggernaut of tragedies that he is powerless to stop. And before long, he’ll be crushed under its weight too.

Pereira simply imagines Ramu/Rama as a “nameless cog in a larger and destructive machine”. It’s an unforgiving view of a holy figure – one that terrifies and also evokes pity. The demolition of the Babri Masjid and its fatal reverberations in Mumbai are still lodged in Valmiki Rao’s memory – he does not know the full extent of the damage in both places and the number of lives destroyed, but what he does know is that this is a nation that never learns from history. Or from its holy texts. More than three decades have passed since the riots, but intolerance remains a potent drug – it makes man crave unrest and distorts his reality. Time, instead of healing, simply numbs the effects.

The Ramayana is eternal – not just because it’s a feat in storytelling but because its warnings against fanaticism and blind belief will be relevant in every age. The Memoirs of Valmiki Rao simply refreshes our memories of 1992 using a medium we understand well – the stories of gods and goddesses.

The Memoirs of Valmiki Rao, Lindsay Pereira, Penguin India.

Courtesy: The Scroll