By Rajan Narayan

THE University Hostel in Bengaluru where I did my BA (Hons) in Economics was located at the Majestic Circle. This area had more than 15 theatres showing Kannada, Tamil, Hindi and English films. I used to work as a booking clerk in one of the best theatres in the area. When a new film was released at least the first 100 people in the queue were the black marketers. The black marketers hired young boys to stand in the queue and buy four tickets each which was the maximum number of tickets per person allowed. They did not see the film themselves but sold the tickets in black to latecomers.

However, as a ticket booking clerk at the counter I used to get to see the films for free whenever I could. My love for films did not end. Later when I moved to Bombay and joined the Financial Express the paper had no film critic. Since I was interested in cinema, I volunteered for the job. The major advantage was that unlike the janata, as a media film critic I got to see the new films at media previews organized in smaller auditoriums, before they were released for public viewing. The media previews before the release of the film to the public were drab or plush mini-auditoriums sometimes incorporated in the main theatre complex itself. These preview mini auditoriums could take a capacity of 20-50 viewers.

These were also used by producers to screen their films for distributors. With any cinema around the world it is the distributors who take the biggest risk and even before a film is completed distributors bid for the rights of exhibition in various territories.

For instance, a particular distributor may bid for certain exclusive rights. The most expensive of course were the rights for Bombay city. It is the distributors who book the cinema halls or theatres for screening of the films whose distribution rights they have bought. It is the distributors who make a lot of money if a film is a hit and they lose money if the film is a flop and there is no public rushing to see it.

The price films depend on the actors. The main evil of the Indian cinema is the star system where the distributor may purchase a film only if the lead role features Shah Rukh Khan or Salman Khan. But even Shah Rukh Khan films like “Fan” fall flat at the box office.

In the early 70s, the Central government had set up the Film Finance Corporation of India. The objective was to encourage the financing of good cinema vis-à-vis the usual song and dance around the trees potboilers without much of a captivating story line. Unfortunately, most of the funds went towards making art films which had no audience.

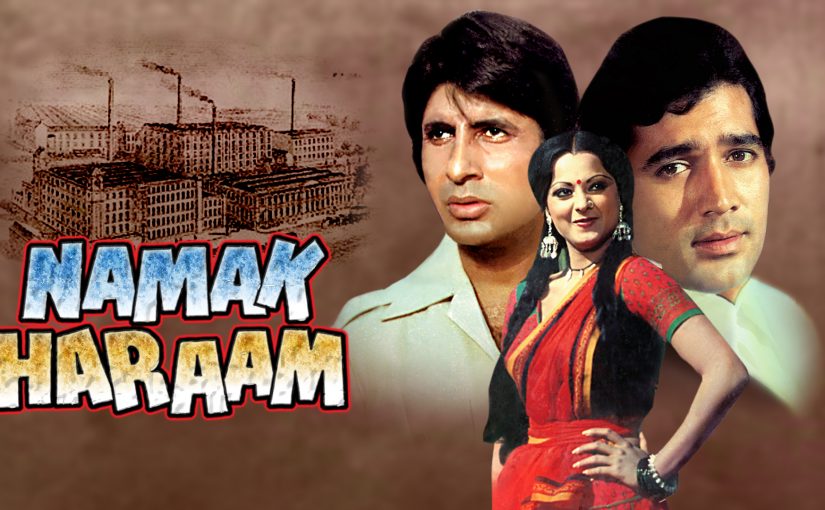

Those days I was convinced that money should be provided for meaningful films even if they had megastars. My logic was that films which had good content matter would have a put major impact on the audience. To prove my point I selected a film called “Namak Haraam” which dealt with the relationship of owners with union leaders in a textile mill. The role of the union leader was acted by Rajesh Khanna and the role of the son of the owner of the mill by Amitabh Bachchan. The film was produced by Hrishikesh Mukherjee.

The film was very successful and attracted a lot of labor class viewers. I decided to have a special screening of the film at the Shanmukhananda Hall in Matunga in Bombay. The director Hrishikesh Mukherjee was very corporative. He persuaded Rajesh Khanna and Amitabh Bachchan to be present during the screening. The audience comprised of factory workers. With the help of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences we administrated a questionnaire to all those attending the screening. This showed that the workers understood the theme of the film. The traditional belief has been that the aam jaanta only comes to films to see their favorite actors.

The results of the survey were published in “Screen”, the most popular film weekly published by the Indian Express Group of Publications. My table at the “Financial Express” was next to that of the reporters of “Screen.” My friend, the late Ali Peter John was a senior reporter at “Screen.” All the top most actors used to come to visit him for publicity. This included Dharmendra and even Raj Kapoor and Hema Malini. In a case of reverse snobbery none of us working at the “Financial Express” would even acknowledge the film stars who passed our table to go to the “Screen” section. Courtesy Ali Peter John I even attended several Bollywood parties. After my initiative study on “Namak Haraam” was published I was invited to be judge for the “Filmfare” critics awards.

It was a very exciting experience but very tiring. There were two other judges apart from me and they were Bikram Singh, an assistant editor “Filmfare” and Dilip Padgaokar, then resident editor of “The Times of India” in Bombay. The films were screened for us in preview theatres. Most of the screenings were in the evening accompanied by cocktails and dinner. It was hard work as we had to see two to three films per day. We had to watch very carefully because we had to give marks with comments on every film.

Most of the films screened were heavy art films like “Dhuvida” by Mani Kaul which was the favorite of the arty types like Dilip Padgaokar. I preferred a down to earth called “27 Down” made by Awtar Krishna Kaul in 1974. The film used the Bombay suburban train metaphor to depict how monotonous life can be for those employed in offices in Mumbai. The life of most working people in Bombay or Mumbai was dictated by the suburban trains. It made a world of difference whether you are able to catch the 8:15am train from Borivali which would reach Churchgate at 9:30am in time for work at 10. Similarly everyone would run to catch the 5:20pm train in the evening to get back home early enough for whatever domestic jobs awaited them. Awtar caught the spirit of the life of the working person in Bombay very dramatically.

I voted for an award for “27 Down.” The other two judges with Dilip Padgaokar were in favor of “Dhuvida.” I protested very strongly. This led Dilip Padgaokar to call me a Judas at the feet of new cinema. I was invited for the “Filmfare” award ceremony and ceremoniously got a seat in the second row by virtue of being a judge along with top stars like Manoj Kumar, Shatrughan Sinha and Maduri Dixit.

There were two interesting fallouts of my stint at being a judge for the “Filmfare” critics awards. I was invited by Shyam Benegal to witness the shooting of “Manthan”, a film on the Amul Co-operative Society. The film featured Smita Patil and Nasseerudin Shah in the main role. The shooting was at Anand, the headquarters of the Khaira Milk Producers Union.

Over a lakh milk producers had come together to finance the film. Shyam and the top actors were staying at an old bungalow of the Raja of Junagadh Junagad. I was staying with this group. Some of the supportive actors like Mohan Agashe and Varsha Usgaokar were staying in the village. The theme of the film invited attempts by local landlords to stop the co-operative milk society.

I recall that Mohan Agashe, a very good actor, was required to do a scene, his morning ablutions out in the fields. He was very embarrassed as every time he could go into the fields for the shooting the village women started laughing. Finally, he decided to do what the women do. Like the women he covered his face so that nobody could identify the face. Morning ablutions are done in stoic silence without drawing anyone’s attention.

On one starlit night the young Varsha Usgaocar sang the popular English song “Starry Starry Night” while we went for a walk after dinner. One of the most dangerous scene in the film was when the goons of the landlord set fire to the home of Smita Patil in the film story line. The fire almost went out of hand but Smita fortunately escaped any danger or injury to her life.

The film made in the 70s is considered an Indian Hindi cinema classic. A restored version was screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 2023. I was also invited for the first competitive Indian film festival held in Delhi in November 1976. I was asked to present a paper on parallel cinema. The opening film was “Godfather.” Delhi, unlike Goa, has many excellent theatres where films are screened.

I travelled to Delhi by train. While accommodation was provided by the festival authorities we had to pay for transportation. It was bitterly cold in Delhi and I did not have any warm clothes. I had to wrap myself in a blanket. The seminar on parallel cinema was held in Vigyan Bhavan. All the leading filmmakers including Mrinal Sen, the Bengali filmmaker, and Basu Chatterjee of “Khata Meetha” fame were there.

The inaugural address was given by BC Chopra. Chopra shocked the audience of filmmakers and critics by insisting “that films were randi ka pesha (prostitute business).” All the serious filmmakers walked out of the hall and had the parallel cinema meet on the lawns. The critic of the “London Times” who was present was very impressed with my paper on parallel cinema. David Robinson got my paper on parallel cinema published in the “London Times.”

When I got back to Bombay some of us used to go to the Film Institute in Pune to watch the best films of the world. The Film Institute has fantastic film archives presided over by MK Nair. The system was that he would study the catalogue and ask them to screen any film of our choice. Over the weekend we used to see half-a-dozen films back to back.

Back in Bombay there was a film society at Tarabai Hall at Marine line where the best films were shown. Then I lost track of filmi duniya and came to Goa and only re-connected with films when the International Film Festival of India came to settle down in Goa in 2003 courtesy Chief Minister Manohar Parrikar.

Unfortunately, IFFI in Goa has never touched the high standard of the festivals organized in New Delhi and Bombay.