By Tara Narayan

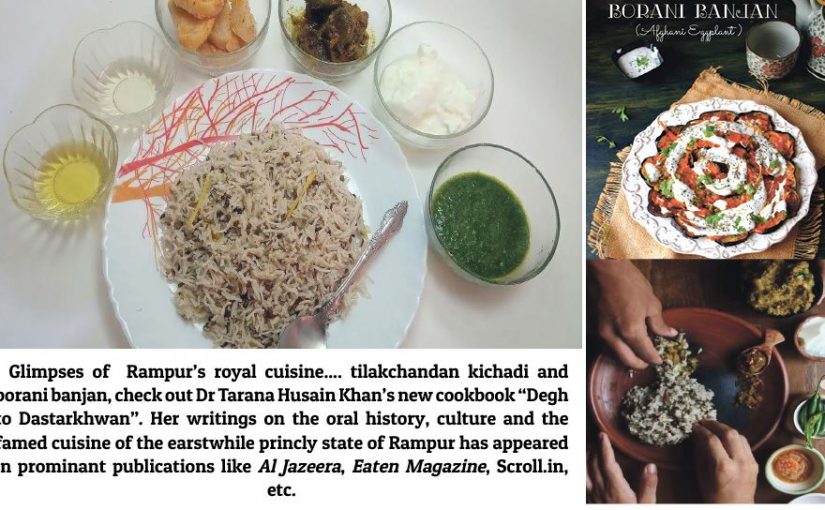

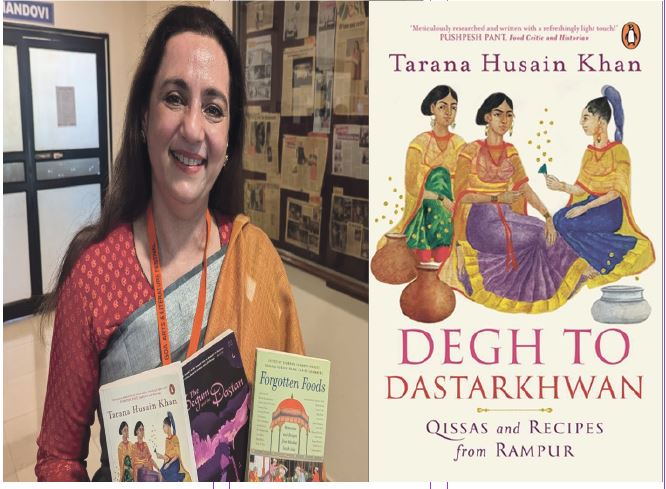

THERE weren’t too many foodie book launches at the Goa Literature & Art Festival at International Center Goa this year on Feb13/14/15 but I was happy to have caught the one in which Tarana Husain Khan’s new book titled “Degh to Dastarkhwan, Qissas and Recipes from Rampur” (Penguin Books, soft cover, non-fiction, Rs400) session in which author Tarana Husain Khan was there in conversation with Anita Ratnam about her book, and the all research which went into her new cookbook to yield a wealth of food stories from yesteryear. Few recognize Rampur for its cuisine, she said, but the royal kitchens cuisine from Rampur is every bit as glorious as that of the other royal kitchens in India’s Moghul era and with a distinctive difference. The most interesting cookbooks catch the imagination with as much story telling as a presentation of recipes fully or half-lost in the mists of time. The author has put in much hard work researching and finding nuggets of interest courtesy Rampur’s fabled Raza Library.

Oh yes, some of the most charming stories revolve around the rulers or monarchs of older worlds, who lived life on a grand scale and sought to move heaven and earth to have the finest cooks in the royal khansama ghar cooking up heart’s desires and much else, making for memorable eating for the many visitors who visited and dined at the royal table…loaded with all manner of food simple as that transformed to memorable dishes.

Food through the times may conjure up the spiritual ambience of a Sufi shrine or various noted khansamas, weddings and funerals of the times when nobody thought of dieting (although life was rough and tough and there certainly were pehalwan games and competitions a la local Olympics perhaps).

Tarana Husain Khan spoke of 40 to 50 kinds of recipes connoisseurs would describe as “gateway to heaven.” All the fine dining going on may yield as many as 50 kinds of pulao (an exaggeration surely!)……for don’t forget the food was created also to remind the Pathan royalty of their native Afghanistan from where they had hailed. Food may have been basic back home but it flowered gloriously in India, presumably land of milk and honey…she spoke at length of “urad kichadi” unique only to Rampur cuisine, it featured the fine grained fragrant “tilak rice” (difficult to find nowadays) now) and much else is in her book about “kababs and forgiving,” “gulathhi and first love,” “Eid sweets and disasters.”

Dwelling on rice recipes she recounted how nowadays we may only find hybrid rice to savor in a kichadi. Rampur kichadi in the royal kitchens were special, the khansamas turned out all kinds of bread but “dal-chawal” was superlative regardless of who ate it up down the hierarchy of upper crust and lower crust lifestyles.

NOWADAYS, she said, food connoisseurs are trying to revive and re-create the lost recipes of old in food festivals in Rajasthan, Delhi, Bhopal and of course the five-star hotels may do themselves proud presenting various period recipes. “Degh to Dastarkhwan” is a fascinating memoir of times gone by and I’m still reading it in bits and pieces, hope to make some of the recipes if I can although mine is a very veggie humdrum kitchen.

But I must confess the author waxing lyrical over the “urad kichadi” had my mouth watering, for these days I’m back to making my own version of kichadi for lunch most daily. My recipe is to have a mix of Pune’s ambemor or Nashik’s Indrayani rice with a spoonful of mixed dal of tur, moong, urad (also urid). Grate in ginger, toss in a few pods of garlic, season with turmeric, sea salt, and pressure cook. A final tempering (tadka) in desi ghee with cloves, jeera, pinch hing…and it’s done. Serve with thin buttermilk spiked with Himalayan red salt (although I’m told there’s some kind of a scam attached to this salt now) laced often with lemon juice, it’s yummilicious even if I say so!

Of course, a far cry from the Afghani-style delicate pilaf, biryani or even pulao with Indian notes in it. India’s many rice-based recipes may evolve to be richly sumptuous or simply sustainable wholesome affairs. Of special interest too are the chutneys, pickles or relishes (kachumbar) which complement kichadi royal or plebian … in Gujarat an evening khichadi meal will come with a tartish buttermilk kadi, which may be down to earth or filled up with veggies like ladies finger or some chopped greens. The Sindhi kadi to is worth raving about despite its non-curd based kadi, this one is made with thin besan (gram flour) batter and features an interesting medley of veggies.

OKAY, no more kichadi talk. But I urge all who like reading chatty cookbooks to try this one – “Degh to Dastarkhwan” by Tarana Husain Khan. It’s an insightful, fascinating read leaving one bemused by how life was once lived by conquerors in a land they settled down and far from their own native homeland in desert country…food combinations which evolved in their court kitchens and homes hinted of nostalgia.

By the way degh to dastarkhwan translates loosely to “pot to carpet on which food is served” (the old-fashioned and I dare say healthier way of eating in many Muslim households, to sit together on the floor en famille, and eat out of a common platter placed in the center)…reading Tarana Husain Khan’s culinary memoirs I’m inclined to think how much sweeter sounding Urdu vocabulary is compared to Hindi (a fusion of Sanskrit and Urdu)! Needless to say all of today’s seemingly marginalized or “useless” languages need to be revived and kept alive if only by scholars.

Otherwise all our civilizations will soon turn into various kinds of kichadi English across the once colonized world! Something like that. A world in which we’re losing freedom of choices and options which make for ease of living, a more terrible scenario…when a wealth of unity in diversity is gone with the wind leaving behind only whispers of a far more gracious, generous and peaceful life long ago. Even when it came to what we put in our mouth to stay alive and happy. Think about all this my friends and don’t just think sitting on fences.

Excerpted from Tarana Husain Khan’s `Degh to Dastarkhwan’….

The Sense of Rampuri Khichdi

I’M a khichdi-challenged Rampuri, a closet kichdi-hater, and if people come to know about my gastronomic abnormality, it will basically translate to sort of social ostracization in Rampur, the land of urad-khichdi fanatics. I can never comprehend this fascination for the boiled urad dal and rice dish which is a staple winter afternoon diet for Rampur Muslims across all social strata. The non-Muslims are less passionate about it. It is what a sarson saag and makka roti meal is for the Punjabis, although they do not eat it nearly every day throughout winter. Enter any Rampuri home in the old city at lunch time and you’ll find a piping hot khichdi lunch in progress with condiments according to means.

My mother is shocked at my strange behavior and annoyed with me every winter. I think the surprise is less due to intentional amnesia rather than the belief that I will get over this unnatural repugnance. I can only blame it on my non-Rampuri father who ate khichdi reluctantly, saying that it were the condiments and accompanying dishes that gave it any taste. Since my father is not around to defend me, I trudge along with my khichdi-loving Rampuri husband to khichdi dawats. Yes, kichdi dawats abound throughout our winters – a nightmare for me. Let’s say that khichdi in winters has more social life than pulao. A khichdi dawat has several subtexts and social layering. It indicates certain amount of closeness, a bond – a genial mix of informality and hospitality. Close friends often invite themselves over for khichdi – this is highly appreciated and indicative of deep kinship. The newly-wed groom, after numerous lavish dinners, finally becomes a part of the family when he is invited for a khichdi dawat at his in-laws’ place. To refuse a khichdi dawat is tantamount to rebuffing an extended arm of friendship and bonhomie. To confess a distaste for the dish is social death. Tongue-in-cheek remarks will echo down generations, and the labels of being a snobbish and angrez will stick forever. We have welcomed a few vegetarian daughters-in-law with open arms but a khichdi denier is unforgivable. So, khichdi it is throughout winters within the loving, informal ambit of Rampuriyat’, with fingers dipping into mounds of khichdi and glistening with ghee.

In the time of our ancestors, when the notion of communicable diseases and infectiions had not marred social proximity, khichdi was served in a large, round, clay dish with dollops of ghee buried in its centre. Three or four people sat around it on the dastarkhwan – a cloth spread on the floor or bench to serve food in Muslim households – and ate, with the ghee percolating down the edges of the dish, frantically mixing chutney, mooli achar, gobhi gosht before it all turned cold. The bonding effect of eating from the same plate now exists in the realm of fantastical food stories.

Luckily, when the Rampuris mean a khichdi meal, it includes gobhi gosht, saag kofta, queema and chicken, along with a host of other condiments – chutney, dahi bada, muli achar, ghee, til oil, etc. So, khichdi is just the base and you add in different combinations of condiments. A chronic conformist, I disguise my gastronomic aberration by taking a tiny spoonful of khichdi and piling it with the curries.

Some Rampuris are so loyal to the dish that they start eating khichdi from late September and gorge on it till April. But the traditional khichdi-eating can only begin when freshly harvested rice and urad dal become available. The new rice is softer and can be cooked with very little water and there is a fresh edge to the new urad dal. But before the khichdi season is declared, the lady of the house must prepare the mooli achar, which consists of boiled radish slices in spicy water, kept in the sun till it matures. The mooli slices and water are also put into the khichdi and the water is gulped down after the khichdi meal for digestion.

Rampuris who are forced to leave this land of winter khichdi complain that the khichdi never tastes the same abroad. I remember that new rice and dal were brought from Rampur every winter at my grandparents’ house – the umbilical cord never severed after decades of moving to Aligarh. Some fanatics living outside Rampur even carry water in large plastic jars in the belief that the taste of the khichdi is enhanced by Rampuri water. The urad dal khichdi is only confined to the earlier Rohilla Pathan belt central around Moradabad, Bareilly and Shahjahanpur. East of Shahjahanpur, according to Rampuris is, all poorab, the land of the arhar dal and moong dal khichdi. Moong dal khichdi (which I prefer) is allowed only in case of an upset stomach.

Till the 1980s, khichdi was cooked only withtilak chandan’ rice, a highly aromatic, small grained local variety which has become almost extinct now, ousted by the high yielding hybrid varieties. Old-timers still lament about the disappearance of tilak chandan rice and its fabulous aroma which announced that khichdi was on boil.

Today, Rampuri khichdi consists of rice and urad dal boiled with salt, peeli mirch (dried yellow chillies) and slivers of ginger. It is the simplest dish is itself as no oil or aromatic spices are ever used. But the proportion of rice and urad dal as well as the soft, slightly fluffy texture comes with years of practice.

The khichdi used to have elaborate versions too, as I found in my translation of the manuscripts of Persian cookbooks. There used to be a khichdi pulao,’ which had meat cooked with ghee spices – to make a yakhni stock – and married to the moong dal khichdi. Similarly, recipes of dhuli khichdi and muqasshar khichdi have moong pulses, rice and meat, cooked with ghee and spices. Gujarati khichdi and bhuni khichadi were the non-meat khichdis, and dated back to the Mughal era. The most interesting recipe is of khichdi Daud Khani, possible named after the founder of Rohilkhand or a Mughlai nobleman; it consists of moong pulses, rice, mincemeat, spinach and eggs – a complete meal for a warrior! Interestingly, most of the khichdi recipes use moong lentils and rice as the base, but the quintessential Rampur khichdi uses urad lentils, maybe because urad is more commonly grown in the area. There is no mention of urad dal khichdi, which we call Rampuri khichdi in the Raza Library manuscripts. Probably, the humble urad dal khichdi was too simple to be included in the cookbook manuscripts which drew inspiration from the grand Mughal and Awadhi cuisines. However, oral history is replete with instances of the Nawabs of Rampur relishing the urad dal khichdi.

My grandfather-in-law, Ameer Ahmad Khan, riyasat engineer and chief secretary to Nawab Sayed Raza Ali Khan (ruled 1930a-1949), was sometimes called for a khichdi meal at 3 a.m. the Nawabs stayed up all night entertained by music and dance mehfils. Urad khichdi was a great favourite of Rampur Nawabs who enjoyed both the royal as well as the plebeian cuisine.

An interesting account of Nawab Sayed Hamid Ali Khan is narrated by Sayed Muhammad Yameen in Urdu Digest (February 1968), which he heard from his father-in-law, Colonel Sayed Ahmad Hashmi, when he was posted at the Nawab’s court. The story goes that Nawab Sayed Hamid Ali Khan was eating biryani one day, and he found a piece of bone in the rice. A jhamadar used to be present at the meal with a whip, and a maulvi recited thebismillah’ incantation at every morsel the Nawab raised to his royal lips. The biryani cook was summoned and whipped for his carelessness. On another day the Nawab was partaking of his favourite urad dal khichdi. He happened to appreciate the dish and called the cook to reward him. It was the same cook who had been whipped for his biryani. The cook said, Huzoor, my father was the biryani cook at your grandfather Nawab Sayed Kalbe Ali Khan’s court. Once he cooked khichdi for Sir Sayed Ahmad Khan, founder of Aligarh Muslim University, who was a state guest. The Nawab was pleased and wanted to reward him, so my father requested that, of his four sons, he wanted three of them to be educated at Aligarh Muslim Univerasity and their education be sponsored by the Rampur state. So, while my brothers went to the University, I stayed back to learn my father’s skills and serve Your Highness. Now, I have four sons and I request Your Highness to give me the same reward for my khichdi.’

After confirming the story, the Nawab sent the cook’s three sons to Aligarh Muslim University. In Rampur, fortunes can change with a well-cooked khichdi.

My writings on Rampur cuisine and tilak chandan rice evoked the interest of historian Professor Siobhan Lambert-Hurley from the University of Sheffield. As we connected over Skype calls, Professor Lambert-Hurley and Professor Duncan Cameron – plant scientist at the Institute for Sustainable Food, University of Sheffield – put together a proper project for resurrection of tilak chandan and revival of heritage recipes,Forgotten Food: Culinary Memory, Local Heritage and Lost Agricultural Varieties in India’ – funded by the Art & Humanities Research Council in the United Kingdom and executed under the lead of University of Sheffield – was born in November 2019. An integral part of the project was growing tilak chandan in Rampur and attempting to resurrect it by making the plants disease resistant through plant biology interventions in special plant labs at Sheffield. After a fantic search for tilak chandan seeds in the middle of the pandemic, we were able to locate the elusive seed, get its authenticity confirmed by Professor Cameron and grow it at the historic Benazir farms in the shadow of the ruins of Benazir palace of the Rampur Nawabs. In December 2020 after several twists and turns, which included a freak storm a few days before the harvest, we were able to reap the almost mythical tilak chandan.

I organized a khichdi dawat for my friends – a sort of taste test for the newly harvested tilak chandan. This was a part of the blind test we had planned under the project. As the khichdi simmered, I caught a whiff of something forgotten, an aroma of my childhood and youth. Since it was new rice, it tended to become lumpy even when cooked with little water. Old-timers say that the traditional Rampur khichdi made from new rice and new lentils was supposed to be soft and kind of sticky in texture. No wonder my mother prefers a slightly overcooked khichdi. Tilak chandan is a smaller and plumper grain than the hybrids we had become used to, and when I served the khichdi with spoonfuls of clarified butter, each gain was completely coated in a way that long grained hybrid rice could not aspire to. To make things exciting, I also cooked khichdi with long grained basmati rice. The texture of basmati rice khichdi was fluffy but had no aroma. My eight unsuspecting friends were all in their forties and fifties, had lived in Rampur for years and had been exposed to the tilak chandan khichdi till the 1990s. One couple had continued to grow tilak at their farms. I served the basmati khichdi first and then the tilak khichdi and was gratified to note that everyone turned to the tilak khichdi as they were jolted out of their taste amnesia. They gushed over the aroma, abandoned their forks to mix ghee with their hands, savouring every bite. My one non-Rampuri friend, who had been married into Rampur, however, preferred the basmati khichdi for the texture. Seduced by the ricey tilak chandan aroma, I almost got over my khichdi-hate.

Khichdi: An Eternal Love Story

Bisma Tirmizi writes in Feast: With a Taste of Amir Khusro that khichdi belonged to the soil of the subcontinent and the conquerors over the ages fell in love with the dish. The word khichdi’ has Sanskrit roots, and the Greek king Seleucus I Nicator during his campaign in India (305-303 BC), wrote that pulses cooked with rice is a popular dish among people of the Indian subcontinent. Ibn Batuta wrote in his account of India (1340),the munj (moong) is boiled with rice, and then buttered and eaten. This is what they call “Kishri” and on this dish they breakfast every day.” Raaz Yazdani, poet and historian from Rampur, writes that when Nadir Shah invaded India in the eighteenth century and saw Indians eating pulses, rice and roti together, he is said to have remarked with surprise,

Een hindaan ghalla ra ba ghalla mee khurinda

(these Hindi people mix grains with grains and eat)

Pulses were a novelty to the Muslim conquerors as indeed was khichdi. The Mughals used several aromatic spices and khichdi became a great favorite with them. They granted them grand names like Khichadi Shahjahani, Khichdi Mahabatkhani, etc – names which were transcribed into cookbooks and carried on for posterity. It is said that Mahabat Khan, a Mughal noble, ate only one meal a day and millet-rice khichdi was always a part of the repast. One reason for the metamorphosis of this humble peasant fare to high cuisine was the ritual abstinence from consuming meat practiced by the Mughal emperors from the time of Emperor Akbar. Akbar ate khichdi on his meat-abstinence days and it finds mention in Ain i Akbari. It was a favourite preparation of Emperor Jehangir, Aurangzeb craved for chickpeas khichdi during his campaign in the Deccan; he also ate a variation of khichdi called the Alamgiri khichdi which had boiled eggs and fish. The British and the Anglo-Indians reinvented khichdi into kedgeree’ cooked with fresh fish for breakfast. But the unpretentious khichdi survives in its simplest and from-the-heart in Rampur – a late breakfast meal for the male members before they leave for work, or a lazy lunch before siesta in the sun. Because of its simplicity, khichdi should be the perfect dish for funerals, right? Bisma Tirmizi describes khichdi served is never served to the mourners after a funeral. However, in Rampur, khichdi is never served at funerals because there are so many condiments that must accompany it that it would be a strain on the mourners. So, pulao comforts the bereaved while khichdi continues to be the dish for leisurely celebration of winter. During Ramzan, the wake-up call for sehri – the meat consumed before dawn by the fasting Muslims – begins at 2am on the loudspeakers. It is a bit early. The mauli often calls out,Hazraat, it’s time for sehri. Start cooking your khichdi.’ The shaukeen (foodies) have khichdi even for summer fasts, although people say that it makes you very thirsty.

Once, I found senior students of my class enjoying a khichdi repast during the lunch break, with khichdi brought in casseroles complete with condiments and gobhi gosht. That was one khichdi invite I could refuse because of my exalted position of a teacher.

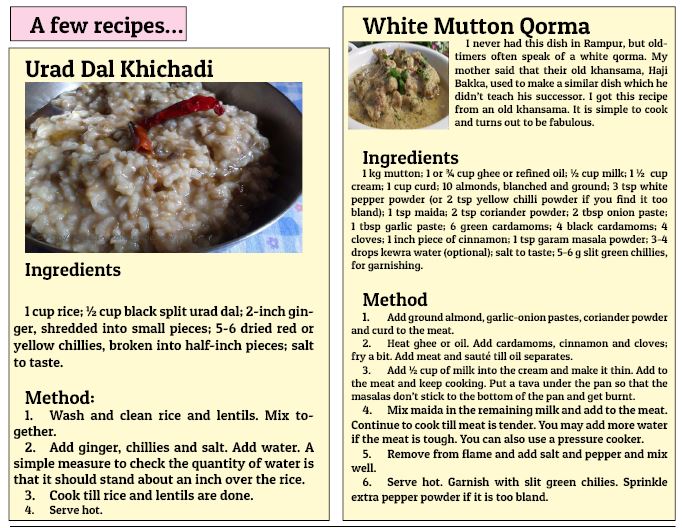

Note: The cookbook is replete with many recipes… variety of qorma, khichdi and khichda, famed kababs, gulathhi, dahi phulki, Rampuri stew…more, and the forgotten tantalizing sweetness of adrak halwa!)