WHEN I first saw her, she was barely a few days old — a tiny, fragile baby, born with a severe congenital heart defect. Her diagnosis? Single ventricle anatomy. At the time, the condition felt like a death sentence. But her father refused to give up. He looked at me with a kind of quiet desperation and said, “There must be something we can do.”

That child would go on to become one of the most inspiring cases in my career. Thanks to the brilliance of Dr Devananda NS (cardio-thoracic vascular surgeon) from Manipal Heart Hospital, who regularly visited Goa, and a series of complex procedures over the years, she reached what we call “Fontan completion.” Years later, she returned — alone. Her father had passed on, but she stood in front of me, confident, determined to finish her studies and live an independent life. That moment remains etched in my heart as proof of how far we’ve come in treating congenital heart disease.

Another case I remember vividly is that of a young boy from a remote village in Goa. He was diagnosed with Tetralogy of Fallot — a serious cyanotic heart defect that leaves children breathless even during mild activity. His parents were terrified. But we were able to guide them through the process of corrective surgery, which was performed successfully in Bengaluru.

Today, he is a lively teenager who plays football with his friends, and barely remembers the days when he couldn’t climb a single flight of stairs without gasping for breath. Watching his transformation was like witnessing a second birth.

What is congenital heart disease?

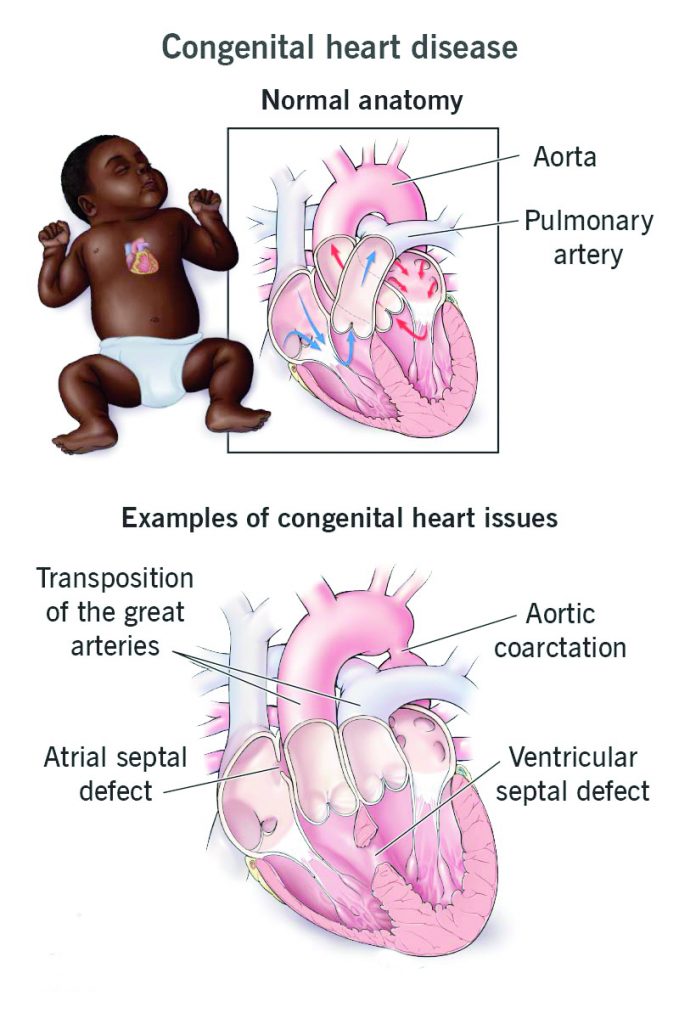

CONGENITAL heart disease (CHD) refers to a range of structural problems with the heart that are present from birth. These conditions can affect how blood flows through the heart and body. Some are simple and may not need treatment, while others are life-threatening and require immediate intervention.

The story of congenital heart disease in India is no longer just about survival. It’s about hope, resilience, and transformation.

What is the most common CHD in India?

THE most common congenital heart defect is a ventricular septal defect (VSD) — a hole in the wall that separates the two lower chambers of the heart. Its prevalence is around 3 to 5 per 1000 live births. A related and also common condition is the bicuspid aortic valve (BAV), where the valve has only two leaflets instead of the normal three.

What is the difference between a congenital and a critical congenital heart defect?

CONGENITAL heart defects can range from very mild conditions that may never need treatment to extremely severe ones that threaten life in the first few days or weeks. The most serious of these are known as critical congenital heart defects (CCHD). These often require urgent surgery or catheter-based intervention in the newborn period.

Types of CHD and how they work

THERE are many kinds of CHD — some affect oxygen levels in the blood (cyanotic defects), while others do not (acyanotic defects). Examples include aortic valve stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, patent ductus arteriosus, pulmonary valve stenosis, septal defects like VSD and ASD, tetralogy of Fallot, transposition of the great arteries and single ventricle defects.

In a normal heart, blood flows in a precise path: from the body to the right side of the heart, then to the lungs for oxygen, and finally to the left side of the heart to be pumped out to the body. CHDs disrupt this flow in various ways, depending on the defect.

Can people with CHD live normal lives?

THANKS to advances in medical science, most children with CHD now survive into adulthood. However, many will need lifelong cardiac care, including monitoring, medication, or follow-up surgeries. CHD is not truly “curable” but it can be managed well, often with an excellent quality of life.

How is CHD treated?

TREATMENT depends on the severity of the condition. Some defects can be managed with catheter-based procedures, where thin tubes are used to insert small devices that close holes or open narrowed valves.

Other cases require open-heart surgery. Over the years, surgeons have developed highly refined techniques tailored to each specific condition.

One of the most remarkable operations in this field is the Fontan procedure, designed for children born with only one working heart ventricle. Through a series of surgeries, this operation re-routes blood so that oxygen-poor blood flows directly to the lungs — bypassing the heart.

In India, it’s estimated that over 200,000 children are born with CHD every year, and about one-fifth of them have serious defects that require surgery within the first year of life.

What if nothing else works?

IN very rare and severe cases, the final option is a heart transplant. This once-rare procedure is becoming increasingly common, with better outcomes and growing success rates.

The road ahead

THERE has been a real revolution in the treatment of congenital heart disease. What was once a diagnosis filled with despair is now a journey filled with possibility. With early detection, access to good pediatric care, and continued follow-up, these children—these angelic little warriors — can live long, full lives.